Some of the rarest animals on Earth are down to just hundreds, or dozens, and the clock is officially ticking.

When we talk about endangered species, the usual image is a slow decline. But for some animals, the pace is anything but slow. Habitat is vanishing overnight. Temperatures are rising faster than they can adapt. Illegal trade, disease, and invasive species are pressing in from every side. Some of these animals are so close to the edge that one storm, one wildfire, one policy shift could tip the scales completely.

Still, not every story is doom. Around the world, people are stepping in with small, scrappy, sometimes wildly creative solutions. From last-ditch breeding efforts to Indigenous-led land protections, the work is happening. The question is whether it will be enough, and whether we’re doing it fast enough. These are the species balancing on that edge right now.

1. The saola is so rare it has only been seen a few times in the wild.

Nicknamed the “Asian unicorn,” the saola is one of the most mysterious large mammals on Earth. It lives in the Annamite Mountains between Vietnam and Laos, and we still know very little about it. In fact, no scientist has ever studied a living one in the wild. Most of what we know comes from motion-triggered cameras or animals found accidentally trapped or already deceased.

Its numbers have plunged due to rampant poaching and widespread habitat fragmentation, according to The Saola Working Group. Saolas are often caught in snares meant for other animals, especially in regions heavily affected by illegal wildlife trade. Even though they’re not the direct target, they get caught in the collateral damage of bushmeat markets and forest degradation.

Conservationists are now racing against time to locate viable populations. A rescue and captive breeding program is in the works, led by the Saola Foundation and its partners, who are building a protected breeding center in Laos. But without better enforcement of anti-poaching laws and more protected habitat, this may be the last chance the saola has.

2. Northern bald ibises are hanging on by a thread in Europe.

Once common across Europe, northern bald ibises completely disappeared from much of their historic range by the 17th century. Now they’re back—but just barely. Fewer than 1,000 individuals survive in the wild, with one fragile population moving between southern Germany, Austria, and Italy thanks to an intense rewilding campaign, as reported by the Animal Diversity Web.

These birds look like something out of a prehistoric painting. Their bald, featherless heads, curved beaks, and iridescent black feathers give them a presence that’s hard to forget. Their downfall came from centuries of hunting, habitat loss, and the decline of traditional grazing landscapes that supported their food sources.

The upside? Their recovery is one of Europe’s most coordinated conservation stories. Birds raised in captivity are taught to migrate using human-led microlight flights, a bizarre but surprisingly effective solution. It’s not stable yet, but the momentum is real—and with continued EU support, they may just stick around.

3. The vaquita is down to fewer than a dozen individuals.

This tiny porpoise, native only to the northern Gulf of California, is now the rarest marine mammal in the world, as stated by the World Wildlife Fund. The latest population estimate puts the number somewhere between six and ten individuals. That’s not a typo.

The biggest threat has nothing to do with pollution or climate—it’s fishing. Vaquitas drown in illegal gillnets set to catch totoaba, another endangered fish whose swim bladders fetch absurd prices on the black market in China. The nets aren’t meant for vaquitas, but they trap and kill them anyway.

Attempts to create a safe sanctuary failed. Now, conservationists are focused on removing gillnets and patrolling the area aggressively. Surprisingly, the remaining vaquitas still appear healthy and capable of reproducing, which has given scientists a flicker of hope. But without full enforcement of gillnet bans, hope alone is not going to be enough.

4. Hawaiian monk seals are rebounding—but one oil spill could change everything.

With only around 1,600 individuals left, the Hawaiian monk seal is one of the few critically endangered marine mammals showing signs of slow recovery, according to National Geographic. But the margin for error is razor-thin. Most of the population lives in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, a remote string of atolls that are particularly vulnerable to climate change and marine debris.

Monk seals face all kinds of threats—shark predation, disease, entanglement in fishing gear, and rising sea levels that are washing away their pupping beaches. Add in the risk of a single oil spill near the breeding grounds, and everything could fall apart in one season.

On the bright side, local efforts are working. Hawaiian organizations and federal agencies run disentanglement teams, conduct regular health checks, and actively relocate pups from shrinking beaches. These seals are getting more hands-on help than most wild animals ever do. But their future still hangs in the balance of how fast we act.

5. The Axolotl is almost extinct in the wild but thriving in classrooms.

Everyone recognizes the axolotl—the smiling amphibian with pink gills and cartoon-like charisma. But what most people don’t realize is that wild axolotls are nearly gone. Native only to the ancient lake system of Xochimilco in Mexico City, they’ve been pushed to the brink by water pollution, invasive species, and urban sprawl.

What makes this worse is how many axolotls exist in labs and pet tanks. Millions. The captive population is massive, but genetically shallow and not suited to reintroduction without serious prep. Meanwhile, their wild cousins—adapted to a very specific freshwater habitat—are barely hanging on.

Conservationists are restoring parts of the wetland canals and building floating islands with native plants to clean the water. There’s even a push to use the axolotl’s cultural significance in Mexico to rally broader public support. But unless habitat restoration keeps pace, we may end up with a species that only survives behind glass.

6. The Tapanuli orangutan is the world’s rarest great ape.

Found only in a remote highland forest in northern Sumatra, the Tapanuli orangutan wasn’t even recognized as a separate species until 2017. That makes it the newest and rarest great ape in the world, with a population estimated at fewer than 800 individuals.

Unfortunately, that same year, plans were approved to build a massive hydroelectric dam in the middle of its only habitat. Fragmentation, road construction, and poaching followed fast. And because the Tapanuli lives at higher elevations than other orangutans, relocating them isn’t an option.

The international conservation community pushed back hard, with lawsuits and petitions aimed at halting the dam’s construction. There’s now a growing campaign to secure permanent protections for the remaining forest and to restore habitat corridors. It’s a fight that’s still unfolding. But if the Tapanuli orangutan disappears, it would be the first great ape extinction in recorded history.

7. Kakapos are surviving thanks to technology, helicopters, and round-the-clock babysitting.

The kakapo is a giant, flightless, nocturnal parrot from New Zealand, and yes, it’s every bit as weird as it sounds. It smells like sweet moss, has a face like an owl, and freezes in place when frightened, which worked fine before predators like cats and stoats arrived. Now? Not ideal.

By the 1990s, only about 50 kakapos were left. Conservationists pulled every single one from the wild and relocated them to offshore islands with zero predators. From there, things got intense. Each bird was tagged. Nesting was monitored using infrared cameras. Eggs were hand-reared and swapped between nests like a high-stakes shell game. Helicopters even delivered semen from one island to another for artificial insemination.

And it’s working. As of now, there are over 250 kakapos alive. That’s not a big number, but for a bird this bizarre and specific, it’s a miracle. The comeback depends entirely on people, but the will is there, and that counts for a lot.

8. The Addax is disappearing from the desert it once ruled.

The Addax is a pale, spiral-horned antelope built for the Sahara. It can survive on almost no water, handle brutal heat, and live in sandstorms that would break most creatures. And yet, there are now fewer than 100 left in the wild.

Oil exploration, poaching, and off-road vehicles have destroyed the Addax’s last strongholds in Niger and Chad. Most sightings today are from camera traps or aerial surveys. They’re so rare that entire seasons go by without a confirmed observation. Meanwhile, hundreds of Addax live in zoos and conservation centers, waiting for conditions to improve.

Some of those captive-bred Addax are being slowly reintroduced into protected reserves. It’s not fast, and it’s not easy—this is one of those species that may never thrive again without massive political cooperation. Still, a few groups, including Sahara Conservation and the government of Chad, are trying. If they stop, the Addax probably does not make it to 2035.

9. The Yangtze giant softshell turtle might already be too late.

There are few wildlife stories as heartbreaking as this one. The Yangtze giant softshell turtle is one of the world’s largest freshwater turtles—and possibly the rarest. Just three individuals are known to be alive. One male lives in China, and two others are believed to be in Vietnam. That’s it.

The tragedy? The only known breeding female died during a failed artificial insemination attempt in 2019. For years, scientists had been trying to get her and the male to reproduce, but nothing worked. Her death hit hard, and since then, the remaining turtles have remained elusive and mostly inaccessible.

Still, conservationists are not giving up. Efforts are now focused on locating other wild individuals in remote Vietnamese lakes. Locals have reported sightings, and some searches are ongoing. If even one more female is found, the plan is to move fast with improved breeding techniques. It’s a long shot, but it’s the only shot left.

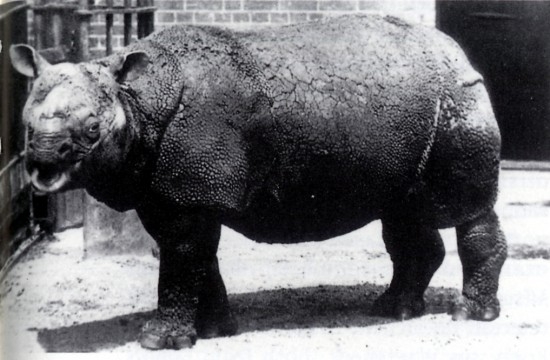

10. The Javan rhino is down to one population, one forest, and no room for error.

Only about 80 Javan rhinos remain, all of them living in Ujung Kulon National Park in Indonesia. That’s the entire global population, tucked into one lowland rainforest on the edge of an active volcanic zone. One natural disaster, and they could all be gone.

Poaching used to be the main threat, but now it’s habitat loss, disease, and plain bad luck. Because there’s no second population, and because moving rhinos is logistically difficult and risky, the species is stuck in a conservation bottleneck. For years, there’s been talk of creating a second site. So far, nothing’s happened.

There’s some good news. Births have been documented. Camera traps show healthy calves. And protection inside the park is tight. But without another safe zone or serious long-term planning, the Javan rhino will continue to live one bad monsoon away from total extinction.

11. Gooty tarantulas are being sold online faster than they can be protected.

Gooty sapphire ornamental tarantulas might be the most stunning spiders on Earth—metallic blue, vividly marked, and fairly docile for their size. They live in a tiny pocket of forest in India, and that’s part of the problem. Their entire habitat could fit inside a modest airport parking lot.

On top of that, the Gooty is insanely popular in the exotic pet trade. Despite being protected under CITES, wild-caught individuals still show up in the illegal market. Habitat loss, collection pressure, and general misunderstanding of their role in the ecosystem have left them barely hanging on.

Captive breeding in the hobbyist world has helped reduce some pressure, but it’s not a solution by itself. India has taken steps to protect the remaining wild habitat, but enforcement is spotty. Unless those last forest patches are fully secured, and illegal collection is shut down for good, the Gooty may end up as just a pretty memory on someone’s shelf.

12. The Iberian lynx almost disappeared, but then Spain and Portugal went all in.

Back in the early 2000s, there were fewer than 100 Iberian lynxes left. Roads, development, and the collapse of rabbit populations (their main food source) had pushed them to the edge. Conservationists were worried it was already too late.

But then something rare happened. Spain and Portugal teamed up and threw real money, land, and energy at the problem. Breeding centers were launched. Rabbits were reintroduced. Wildlife crossings were built over highways. Poaching laws were strengthened and enforced.

Today, there are over 1,600 Iberian lynxes in the wild. It’s not perfect—they’re still classified as endangered—but it’s one of the clearest examples that coordinated, well-funded recovery can actually work. The lynx came back from a place few species return from. It’s a rare win, but a necessary one, because it shows what’s still possible when we treat extinction like a deadline instead of a distant worry.