These rugged imports know every trick in the book, and then some.

Most people think aoudads are just goats with better beards, but they are way more tactical than they look. Tracking one is like trying to win a chess match against something that never sleeps. They’re silent, adaptive, and casually thriving in places they were never meant to be. If you think you’ve got the upper hand, it probably means they already left. These animals aren’t just elusive. They’re straight-up professionals.

1. They can flatten against rock and disappear like desert wallpaper.

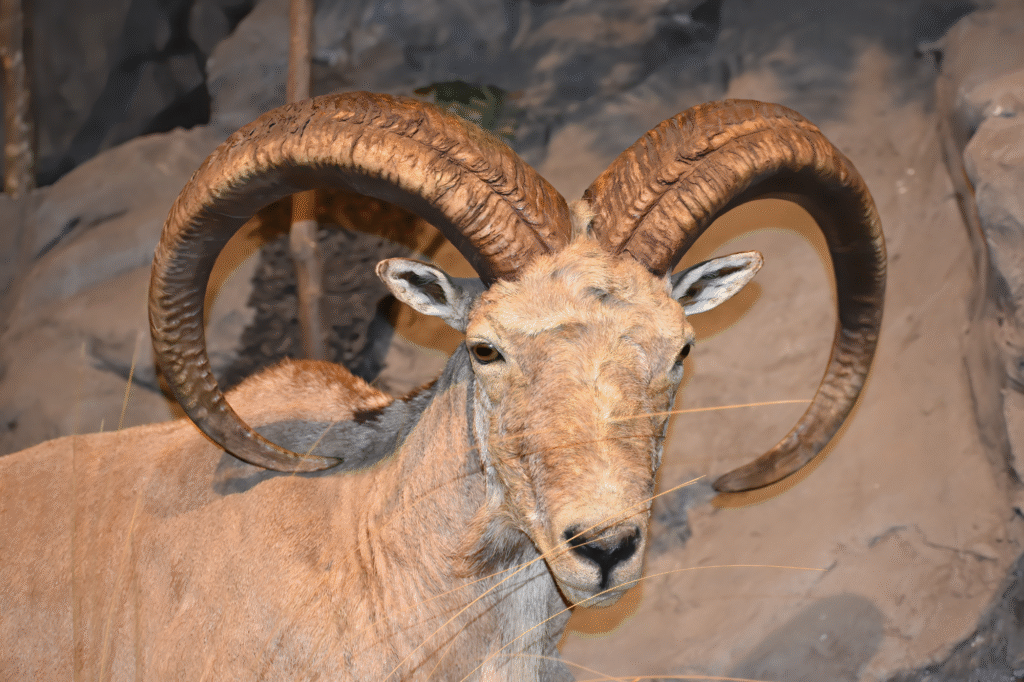

One of the most bizarre things about an aoudad is how something that size can just dissolve into the background, according to Sandro Lovari at Britannica. They don’t crouch or sprint or bolt into a bush. They go still. Like, almost spooky still. And with their sandy-colored coats and shaggy texture, they basically become another part of the rock face. It’s not just camouflage. It’s performance art.

This isn’t just a bonus survival trait. It’s a whole strategy. Aoudads will freeze mid-step and just hang there, even when they’re barely yards away. If you’re scanning for movement or relying on obvious silhouettes, you’re going to miss them over and over again. They’ll stand half in shadow, half in the sun, blending right into canyon ridges that look like they’ve never seen life. You’ll be staring straight at one and still swear there’s nothing there.

Some experienced hunters say they’ve watched an entire group flatten like this while a drone flew overhead. The animals didn’t scatter. They just dropped into invisibility mode and waited for the threat to pass. Unless you’re prepared to glass every inch of rock like it’s a Magic Eye puzzle, chances are, you’re going to be outmaneuvered.

2. Their eyesight is next level compared to other game species.

It’s not just that they see you coming. It’s that they register your body language, direction, and pace like they’re clocking your intentions. Aoudads aren’t like deer who bolt at the first sign of something sketchy, as reported by the experts at the Wild Sheep Foundation. They assess. They calculate. And they often spot you long before you even think you’re in range.

They’ve got wide-set eyes and a field of vision that puts most prey animals to shame. Combine that with their habit of perching up high on ridges, and you’re basically being surveilled by the desert’s most judgmental neighborhood watch. They can clock movement from hundreds of yards out, especially if you’re on the skyline or moving with any kind of rhythm.

And they’re not just reacting to you. They’ll watch and wait to see what you’re going to do next. The second they confirm you’re not just a weird-shaped rock, they’ll ghost out like you never saw them. You might think you’re being sneaky, but to them, you’re a walking red flag.

3. They can scale terrain that would break most other animals.

If you thought mountain goats were tough, aoudads are like the unbothered older cousins who make it all look easy. They don’t hesitate. They don’t test ledges. They just move, almost casually, across steep cliff faces, crumbling edges, and sharp rock outcroppings like it’s just part of the trail, as stated by Gene Haas at the Ultimate Ungulate.

You’ll catch one on a shelf that looks impossible, then watch it hop sideways onto a slope of scree like it’s nothing. Their hooves are narrow, hard, and built for grip in places most boots would slide. And they don’t second guess it. They move with full-body confidence, like they’ve rehearsed every line of the landscape already.

This is why most hunters spot them in places that feel unreachable. You might see one and realize you’re not physically capable of getting to the same elevation fast enough to make a move. They own vertical terrain, and they use it like an exit strategy every single time.

4. They’re not native, and they’re not going anywhere.

Aoudads didn’t evolve in Texas, New Mexico, or the American Southwest, according to Thomas Athens at the National Park Service. They were introduced. But now they’re basically squatters with no intention of leaving, and they’re thriving in a way that almost seems unfair to the local ecosystem. They’re originally from North Africa, where conditions are rough and unforgiving. So when they hit American deserts, they didn’t just survive. They flexed.

There are zero predators putting pressure on them in most of these areas, which gives them free rein to expand. They reproduce quickly, aren’t picky eaters, and can go long stretches without water. Even dry seasons that devastate native game don’t seem to knock aoudads down. If anything, they do better than mule deer and bighorn sheep in head-to-head competition for resources.

The only real control measure at this point is hunting, and even that barely keeps the numbers in check. Most hunters see them as bonus opportunities, but long-term, they’re becoming a dominant force in areas that weren’t built for them. It’s wild how something with no passport and no original claim can still run the show.

5. They rarely make a sound, even when startled.

You know that signature rustle, snort, or crashing noise that gives away most big game when they spook? Aoudads don’t do that. They vanish in complete silence. No warning thumps. No dramatic escapes. Just one second they’re there, the next they’re gone, and you’re left staring at the exact same hillside wondering if you hallucinated the whole thing.

Even when startled, they move quietly. It’s part instinct, part anatomy. Their steps are light, their hooves are compact, and they use natural contours like they know every route. They’ll drop below a ridge line or disappear behind a boulder without kicking up a cloud of dust or dislodging a single rock.

This makes them almost impossible to track by sound. You can’t rely on auditory cues to pin down their location. If you’re not glassing and scanning constantly, you’re going to miss them. It’s not just that they’re elusive. It’s that they’re silent ghosts in places where everything else makes noise.

6. You’ll rarely get a second chance if you blow the first one.

If you mess up a shot or get busted trying to approach, don’t expect the aoudad to give you a do-over. These animals remember. And they don’t hang around to give you time to recover. One misstep, and they’re clearing ridgelines or putting miles between you and them faster than you can reroute.

They’re not the type to freeze up twice. After that first mistake, they’re in full escape mode, usually heading uphill or across terrain that puts a serious buffer between them and any pressure. And once they’re out of sight, good luck finding them again in the same area. They don’t loop back like deer. They relocate.

Some hunters spend hours repositioning only to find the group has moved completely out of range. It’s not panic that drives them. It’s strategy. They move like they’ve been hunted before, and they make sure they don’t repeat old mistakes. The window you get is usually the only one.

7. They travel in groups but make it feel like a solo mission.

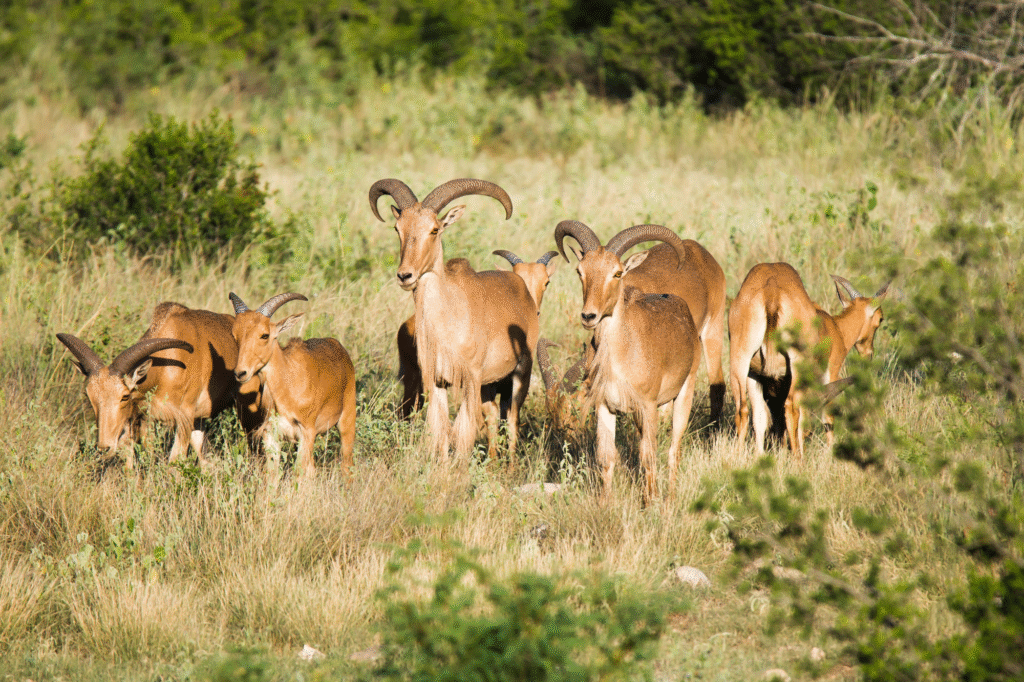

It’s easy to get tunnel vision on one aoudad and forget they almost never roll alone. What’s sneaky is how they space themselves out just enough to make you second-guess how many are really there. You’ll glass one on a ridge, zero in, and then another three will quietly materialize thirty yards apart, like background characters in a video game you didn’t notice loading in.

They move in loose formations, not tight herds. It’s part of what keeps them hard to track and even harder to hunt. A lead ewe might pause out in the open while a dozen others hang back in scrub or shadow, eyes locked on the same thing you’re watching. They communicate without making a sound, and when they move, it’s often in a flowing sequence, not a stampede.

This spacing also means that if you miss one or spook the wrong direction, the rest will scatter with zero pattern. You don’t just lose one shot, you lose the whole opportunity. Hunters who assume they’re only seeing one target often realize too late that there were eyes watching from all angles. The social structure is subtle but effective. It’s a quiet kind of teamwork that makes them way more challenging than expected.

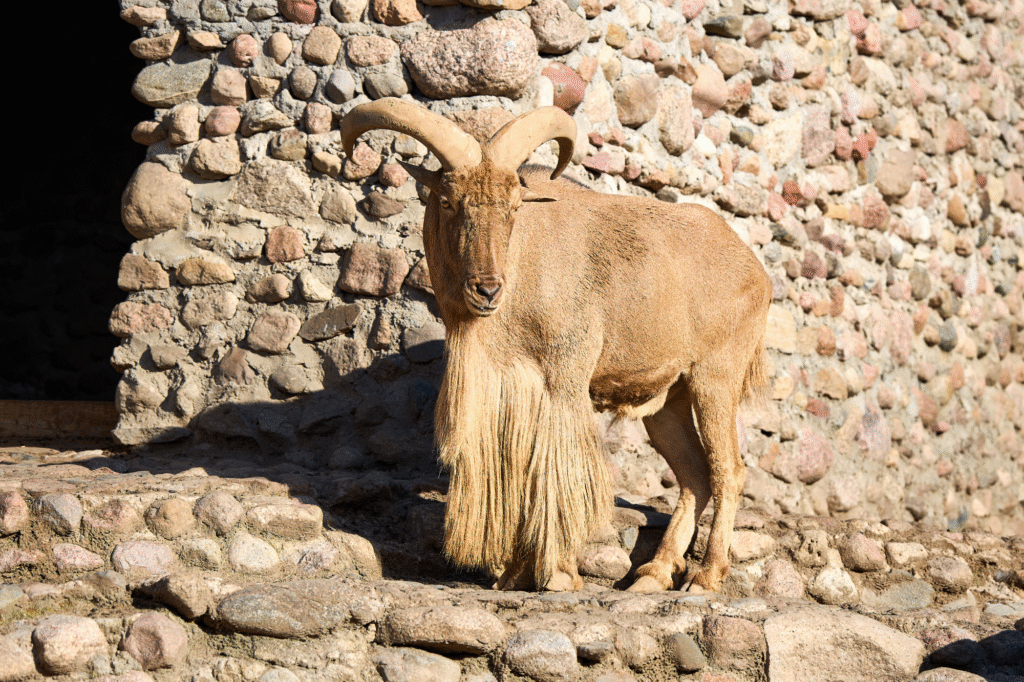

8. Their beards can fool your range finding and your shot.

This sounds ridiculous until it actually happens to you. Aoudads have these dramatic, thick throat manes that hang like tassels, especially on mature males. From a distance, it can make their bodies look larger, lower, or even angled in ways that completely mess with your shot placement if you’re not paying close attention.

Their beard and chest fringe can shift in the wind or obscure their vital zone just enough to throw you off. Even experienced hunters have ended up grazing fur when they thought they were dead center. And at longer distances, it can be hard to tell where the beard ends and the torso begins, which can really mess with quick decisions when the animal is already halfway gone.

It’s not just an aesthetic quirk. It’s part of why judging size, age, and exact position takes a lot more precision with aoudads. If you’re using their body profile as your main guide, those long hairs can throw off your perception and give you false confidence. Knowing this ahead of time means you’ll take the extra second to adjust. That second might be the difference between a clean hit and a complete miss.

9. Their meat quality depends heavily on age and prep.

Aoudads have a pretty split reputation when it comes to meat, and honestly, it depends on who you ask and how the animal was handled. Younger aoudads, especially if processed quickly and cooked right, can taste surprisingly good. Not tenderloin-level, but way better than the gamey, tough horror stories that float around in hunting circles.

Older males, though, are a different situation. They’ve got stronger musk, denser muscle, and a much wilder flavor. If you don’t skin and chill them fast, that intensity gets locked in quick. And if you’re not into long marinades, low and slow cooking, or creative spice blends, you’re going to have a tough time making that meat work for a casual dinner.

Some hunters go in planning only for the trophy and leave the meat. Others swear by it, especially for sausage or smoked jerky. It’s not throwaway meat, but it’s also not plug-and-play. If you’re up for the challenge, there’s a payoff. Just don’t expect it to act like whitetail or elk.

10. They’ll return to the same terrain, but not on your schedule.

Aoudads aren’t nomads in the way some animals are. They have ranges, favorite hangouts, and go-to ridgelines they cycle through. But here’s the thing. Their schedule is chaos. They don’t move through those areas with the kind of consistency that makes planning easy. One day they’re there. The next, they’re a full canyon away. And then three days later, they’re right back where they started.

This can mess with even the most prepared hunter. You’ll scout an area, pattern some tracks, maybe catch a glimpse on a camera or spotting scope. Then, when you show up locked and loaded, it’s like they all vanished. Wait a few days, and boom, they’re back again, chilling like they never left.

They’re also sensitive to pressure. If other hunters or predators come through, they’ll bounce and shift locations faster than most people expect. You have to be willing to revisit areas more than once and accept that timing is mostly guesswork. Consistency with aoudads looks nothing like the dependable routes of deer or elk. It’s fluid, frustrating, and kind of addictive.

11. Their horns can be deceiving when it comes to age.

Those thick, crescent-shaped horns are iconic, but they don’t always give up age or dominance at a glance. Aoudads don’t shed their horns, and the rings aren’t easy to count in the field unless you’re up close. What’s more confusing is that body size and horn size don’t always match. You can have an older male with shorter, thickened horns or a younger one with longer curves that make it look more impressive than it really is.

The base of the horn is often a better clue than the length, but that’s not easy to gauge when you’re glassing from 400 yards out. This has thrown a lot of hunters off who were trying to score a trophy and ended up tagging a younger ram that just had lucky horn genetics.

There’s also variation depending on the region and diet. West Texas rams might grow differently than ones in the Davis Mountains, even with similar age brackets. If you’re basing your shot call purely on curl or width, you could end up misjudging maturity. Learning to read subtle horn features takes time, and even then, the surprise doesn’t end until you walk up to the body. That mystery keeps a lot of hunters hooked.