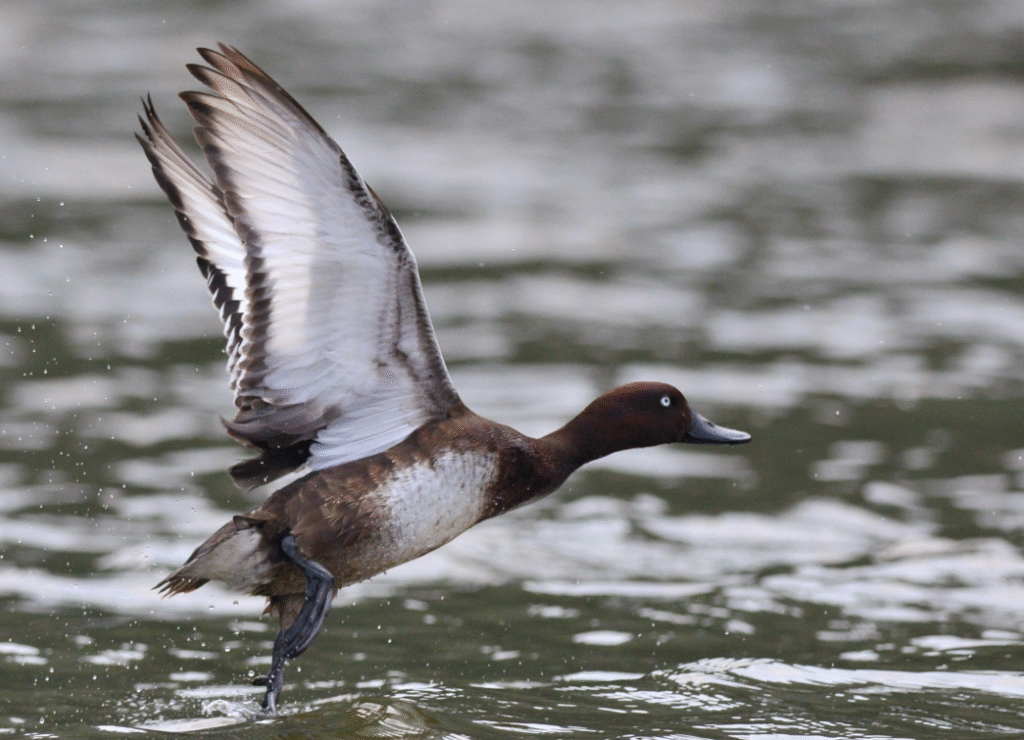

For years, no one had seen one alive—until a hidden lake revealed a tiny miracle.

In 1991, the Madagascar pochard was officially declared extinct. Not functionally extinct. Not critically endangered. Just gone. Scientists had no leads, no nests, and no hope. Then in 2006, something unthinkable happened. A tiny group of the ducks reappeared in a remote crater lake no one had seriously surveyed in years. The story didn’t end with rediscovery. That’s actually where it got way harder. Here’s what went down.

1. Only 25 ducks were left in the entire world when they were found.

It wasn’t some booming comeback. It was 25 individual ducks, hanging on by the slimmest margin. They were spotted in Lake Matsaborimena, tucked away in the north of Madagascar. That crater lake doesn’t have any human settlements nearby, which probably saved them. These birds weren’t thriving. They were barely scraping by. Their numbers were so small, they could’ve vanished all over again without anyone knowing. Rediscovery didn’t guarantee survival. It just bought time.

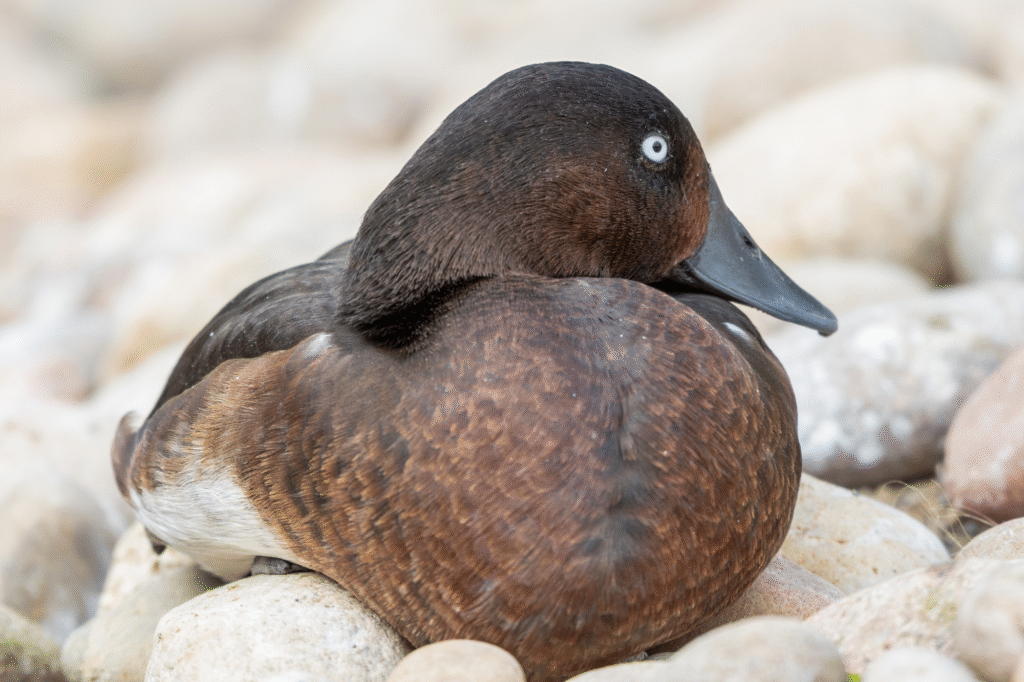

2. They had switched habitats out of desperation and it nearly cost them.

The Madagascar pochard wasn’t even supposed to live in deep lakes. Historically, they lived in shallow marshes and floodplains that had since been drained for farming and rice paddies. So they moved into Lake Matsaborimena, which was colder, deeper, and lacked the food sources their species actually evolved for. Chicks were dying because they couldn’t reach the surface. Adults weren’t finding enough food. This lake kept them hidden but it wasn’t helping them bounce back. It was more of a biological waiting room.

3. No one really knew how to breed them in captivity.

When conservationists tried to breed them, they had almost nothing to go on. Their behavior, nesting habits, feeding preferences—everything had to be figured out in real time. The Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust, alongside Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, had to basically build a duck dating service from scratch. These weren’t mallards. These birds were picky, shy, and deeply tied to their shrinking ecosystem. Getting them to breed in captivity was a miracle on its own. Getting the chicks to survive? That was even harder.

4. Their diet in the wild made them almost impossible to feed in zoos.

You’d think ducks would eat just about anything, but the Madagascar pochard said no thanks to standard pellets and grains. In their natural environment, they relied on aquatic invertebrates, plants, and algae that didn’t exist in managed settings. Captive diets had to be designed from scratch and constantly tweaked. Some chicks failed to thrive, and others became sick from nutrient imbalances. Even with tailored diets, survival rates were a guessing game for years. That slowed down every breeding success they did manage.

5. There was literally nowhere safe to release them back.

Finding ducks was one thing. Finding them a safe forever home was another beast entirely. Their old wetland habitats had been drained, polluted, or filled with invasive fish species that ate eggs and outcompeted them for food. Releasing them back into Lake Matsaborimena wasn’t a long-term solution either. That lake was more of a survival fluke than a suitable home. So researchers spent years scouting Madagascar for potential reintroduction sites, which meant surveying wetlands, monitoring predators, testing water quality, and literally building habitats from the ground up.

6. Reintroduction took a full-on floating aviary experiment.

When conservationists picked Lake Sofia as a potential release site, it came with complications. The chicks raised for reintroduction had never lived in a wild setting before. So scientists built floating aviaries—basically duck-training bootcamps—so the birds could learn how to forage, swim, and survive in deeper water before getting full release. The aviaries let them adjust to their new environment without being totally vulnerable. It wasn’t just about teaching survival skills. It was about unlearning captivity.

7. Locals had to be brought into the plan or none of it would stick.

Lake Sofia isn’t in the middle of nowhere. People live and fish there. So the entire reintroduction project included farmers, fishermen, and kids from surrounding villages. Conservationists didn’t just drop off ducks and hope. They created community gardens to reduce farming pressure, introduced sustainable fishing techniques, and worked on water quality together with locals. The idea wasn’t just saving a duck. It was rebuilding an ecosystem in a way that everyone benefited from. Without that, the pochards wouldn’t have lasted a season.

8. Even today, the total population is only barely above triple digits.

As of the most recent reports, there are still fewer than 150 Madagascar pochards in existence, wild and captive combined. That’s terrifyingly low. One bad season, one drought, or one outbreak could undo decades of work. Every chick that hatches is a small victory, and every loss hits hard. These ducks didn’t just come back from extinction once. They’re still surviving on the edge, one wetland and one human decision at a time. The fight isn’t over. It just changed shape.