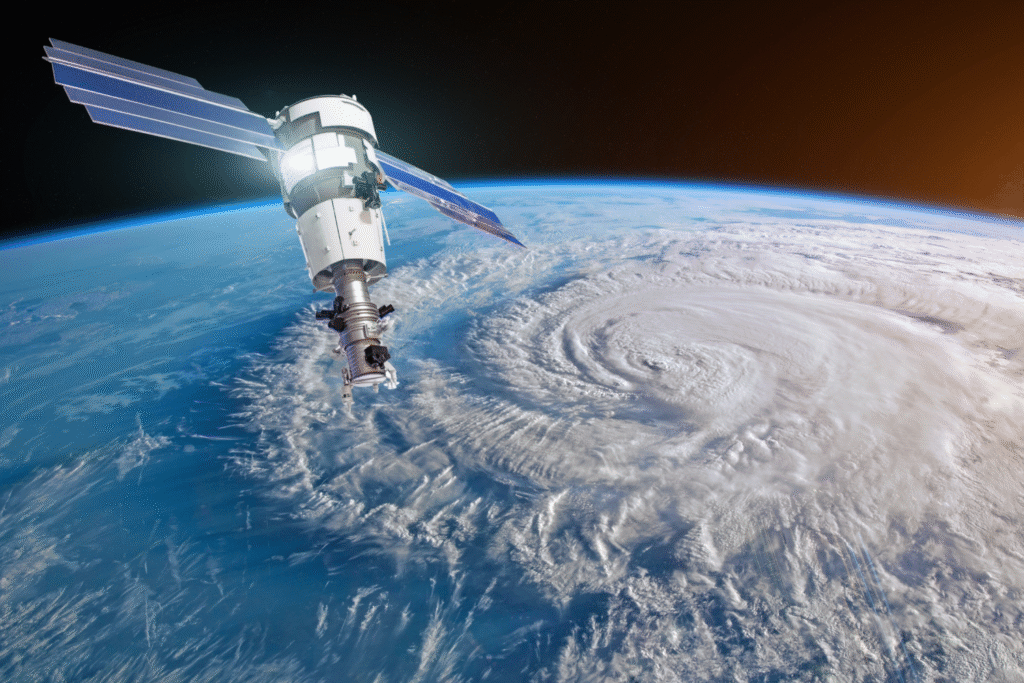

Two new studies reveal that even the world’s last refuges are no longer safe.

The world’s most pristine wilderness areas, once considered safe havens for biodiversity, are witnessing alarming insect population crashes that have scientists deeply concerned. These remote locations, far from direct human interference, are experiencing declines that mirror patterns seen in agricultural and urban environments.

Recent research shows that even our most protected ecosystems cannot shield insects from the cascading effects of global environmental changes. The implications stretch beyond the insects themselves, cutting into the web of relationships that keeps forests, meadows, and islands alive.

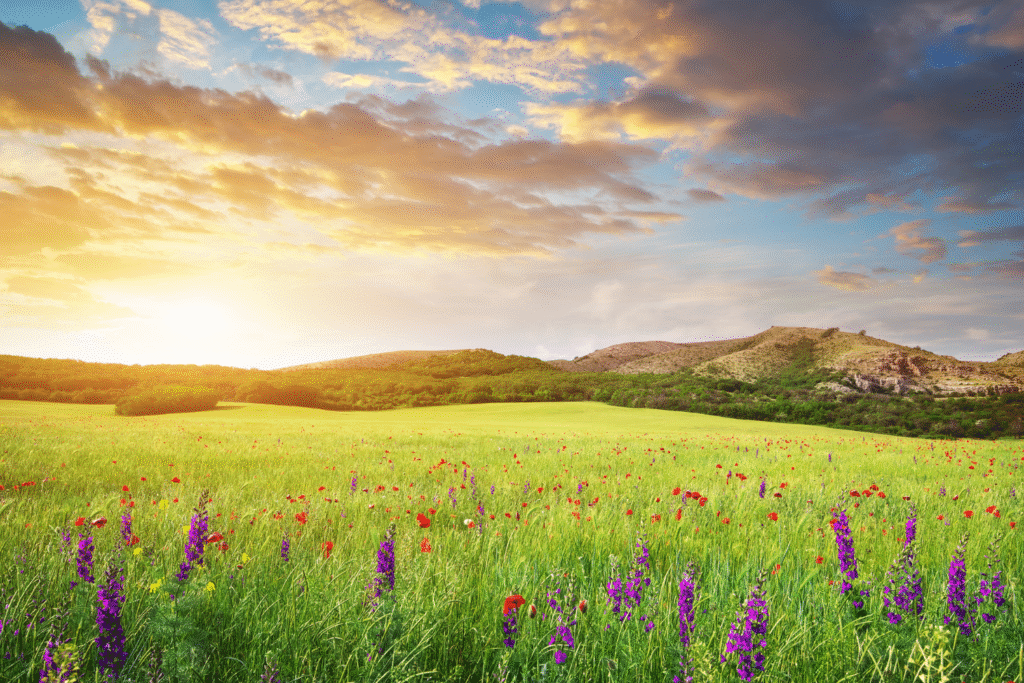

1. A remote Colorado meadow is losing insects at staggering rates.

In September 2025, a study in Ecology found flying insects in a Colorado subalpine meadow had fallen by 72.4 percent over twenty years. At more than 10,000 feet, with almost no human disturbance, the decline was striking. Over 15 summers of monitoring, biologist Keith Sockman recorded an average annual drop of 6.6 percent.

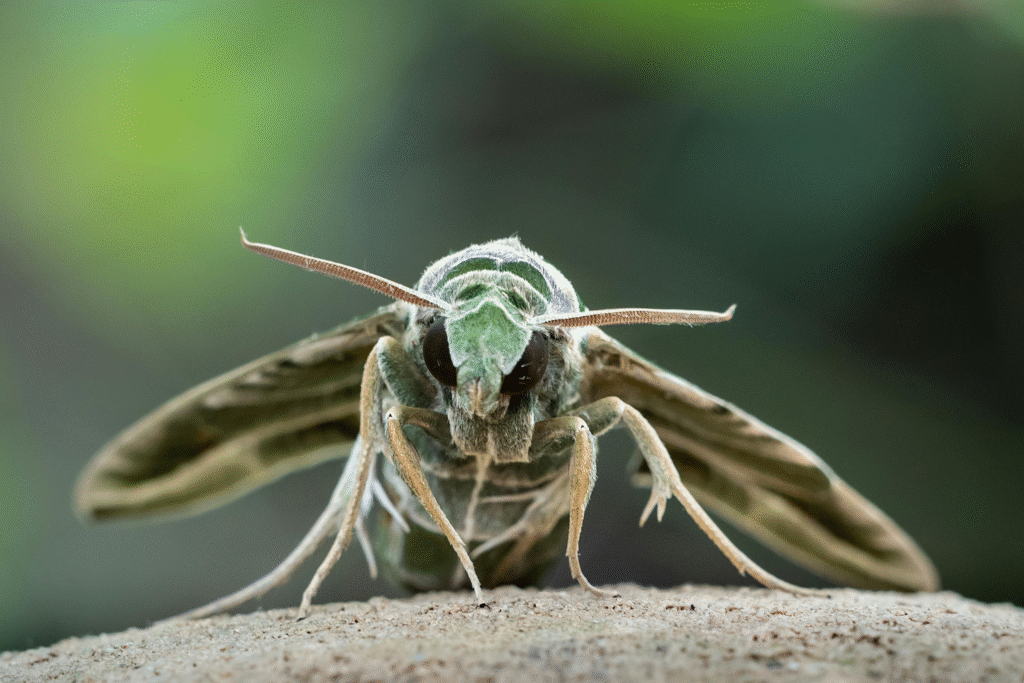

The traps showed fewer bumblebees, hoverflies, fritillary butterflies, noctuid moths, beetles, and leafhoppers. The cause wasn’t pesticides or logging. As Sockman told NPR, “there’s very little human development in the immediate vicinity,” leaving climate change “the most plausible explanation.” Rising nighttime temperatures and hotter summers weakened populations, with steeper losses the following year.

2. Fiji’s ant decline shows that even isolation offers no refuge.

At nearly the same time, another study in Science found that 79 percent of Fiji’s endemic ants are in decline, as reported by The Guardian. Species such as turtle ants (Cephalotes fijianus), big-headed ants like Pheidole caldwelli, carpenter ants (Camponotus macrocephalus), and the tiny Monomorium vitiense are all slipping. They evolved in one of the world’s most isolated island chains, but invasive ants, farming pressures, and climate stress are driving them toward collapse. But centuries of indirect human impact, from invasive ants like the yellow crazy ant and little fire ant to agricultural expansion, have been compounded by climate stress, pushing many species to the edge.

The role ants play in island ecosystems makes the findings devastating. They disperse seeds, enrich soils, and regulate other insect populations. When they vanish, forests lose regeneration power and biodiversity begins to unravel. The takeaway is hard to ignore: if ants can’t survive on remote Pacific islands far from highways and cities, the idea of any untouched refuge starts to collapse.

3. National parks reveal their limits against global shifts.

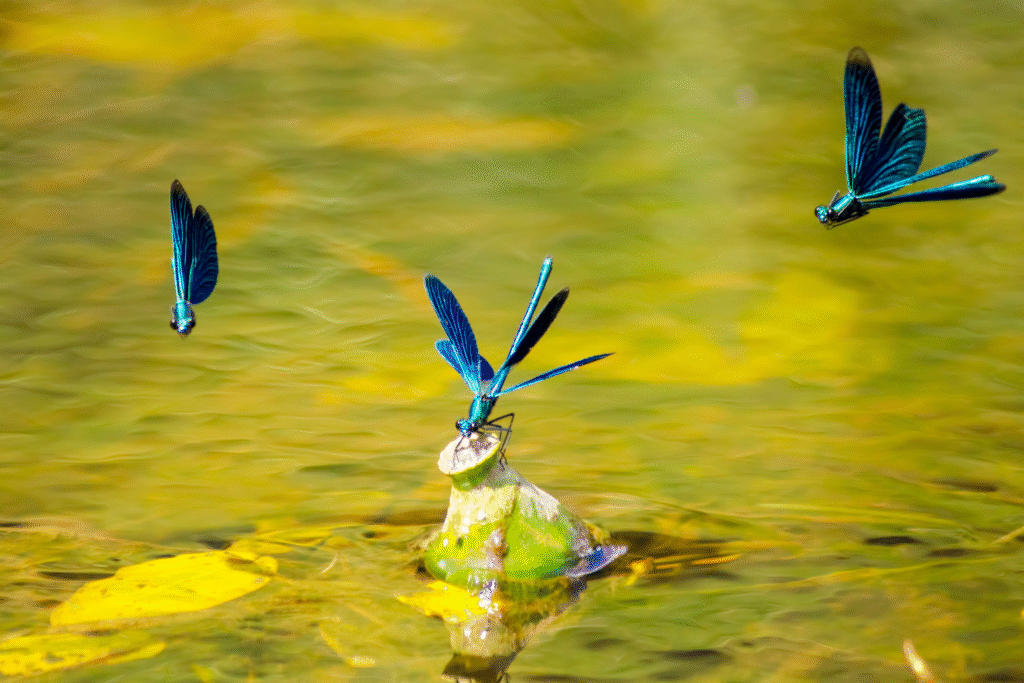

Research summarized in Proceedings of the Royal Society B shows insect declines within parks like Yellowstone and Kruger, despite their protected status. Beetles, dragonflies, and butterflies are thinning even inside these strongholds. Protection on paper can block development, but it cannot shield ecosystems from hotter droughts, shifting rainfall, or the mismatch between plant flowering and insect lifecycles.

That realization reframes conservation itself. We once believed that fences, laws, and boundaries could preserve intact ecosystems indefinitely. Yet the drivers of today’s declines—rising temperatures, disrupted cycles, subtle atmospheric shifts—slip through every barrier. The story is no longer about saving insects in unprotected spaces; it’s about realizing that no boundary can keep out the changing climate.

4. Hot nights are quietly rewriting insect survival.

Cool nights used to give insects a break from the stress of summer heat. Warmer nighttime lows now rob them of those recovery periods. Moths burn through their energy before dawn, mayflies live shorter lives, and entire reproductive cycles collapse under the weight of exhaustion. The change is invisible to us, yet it chips away at populations year after year.

This problem doesn’t require bulldozers or farms to be visible. Meadows still flower and forests still stand, but insects are being eroded from within. The loss doesn’t look like destruction from the outside, but the silence where wings once buzzed tells the true story.

5. Drought traps insects with no way out.

Extended dry spells are stripping landscapes of the water insects need at every stage of life. Larvae dry up in cracked soils, and adults lose nectar when flowers wither. Unlike birds or mammals, most insects cannot migrate to find relief. Entire populations collapse where they stand, leaving ecosystems looking intact but functioning very differently.

That collapse doesn’t stay local. A single dry year can mean fewer pollinators, which leads to fewer seeds and fruits. The following season, birds and mammals depending on those foods face scarcity. What starts with insects silently failing to endure drought spreads into a chain of losses across the food web.

6. Food webs start to falter when insects vanish.

Insects form the base of countless diets, fish in mountain streams, frogs in wetlands, and songbirds in backyards. As their numbers fall, everything above them starts to strain. Birds fledge fewer chicks, amphibians vanish, and bats circle with less to catch. The unraveling doesn’t come with dramatic crashes. It comes through silence: missing calls, empty skies, thinner nights.

The loss of insects is not just their problem. It’s a slow drain of energy from entire ecosystems. Every missing insect means a higher rung of the ladder weakens. And once the base thins, the whole structure begins to sway.

7. Pollination gaps widen when insect partners disappear.

The decline of insects isn’t only about food webs—it’s about reproduction itself. Orchards bordering wilderness zones are already seeing lower fruit yields despite stable farming practices. In wild systems, native plants vanish outright when pollinators disappear, breaking cycles that took centuries to evolve.

The trouble is that the decline is easy to miss. A meadow can still bloom in spring, looking unchanged to human eyes. But if blossoms go unvisited, seeds are not set, and the forest is living on borrowed time. Pollination gaps are invisible in the moment but devastating over generations.

8. Microclimate disruption chips away at fragile habitats.

Insects are specialists, often tied to tiny microhabitats: cool moss beds, shaded creek banks, pockets of damp soil. Climate change reshapes those microclimates even when the larger landscape appears stable. A patch of moss dries, a shaded pool warms, and the insects that depend on those precise conditions vanish.

It doesn’t take sweeping destruction to wipe out a population. It only takes a few degrees, a little less shade, or a subtle shift in soil moisture. These local changes may seem minor, but they add up across regions. What disappears one square meter at a time eventually echoes across continents.

9. Invisible atmospheric changes scramble insect behavior.

Shifts in carbon dioxide change plant chemistry, making leaves less nutritious for caterpillars. Higher humidity disrupts pheromone signals, leaving moths unable to find mates. Altered wind currents redirect butterflies off their migration paths. These shifts are subtle but devastating, eroding the basic behaviors insects rely on.

The meadow still stands, the forest still grows, but the cues no longer line up. Insects miss their signals, fail to reproduce, or starve on food that no longer nourishes. To us, it looks like nature untouched. To them, it feels like a system that no longer makes sense.

10. The decline is rewriting ecosystems worldwide.

The Colorado meadow and Fiji’s islands might look worlds apart, but the message from both is the same: untouched no longer means safe. When even the most remote and pristine landscapes are losing insects, it signals a planetary crisis that no fence, park, or ocean gap can prevent.

The implications reach into forests, fields, rivers, and skies. Ecosystems once considered stable are unraveling from the ground up, their foundations pulled away one insect at a time. What once seemed too abundant to fail is now vanishing, and the silence left behind is louder than the buzz that kept the world alive.