Recycling bins are full of lies we’ve been told for decades.

For years, tossing something into the blue bin has been treated like an act of environmental heroism. But the truth is more complicated, and in many cases, darker. Not everything with a recycling symbol or a green label is actually recyclable, no matter how much we want it to be.

The gap between perception and reality isn’t just frustrating—it’s harmful. Materials that look like they belong in the system can clog machinery, contaminate loads, or simply end up in landfills. The result isn’t just wasted effort, but wasted opportunities to actually make recycling work the way we were promised.

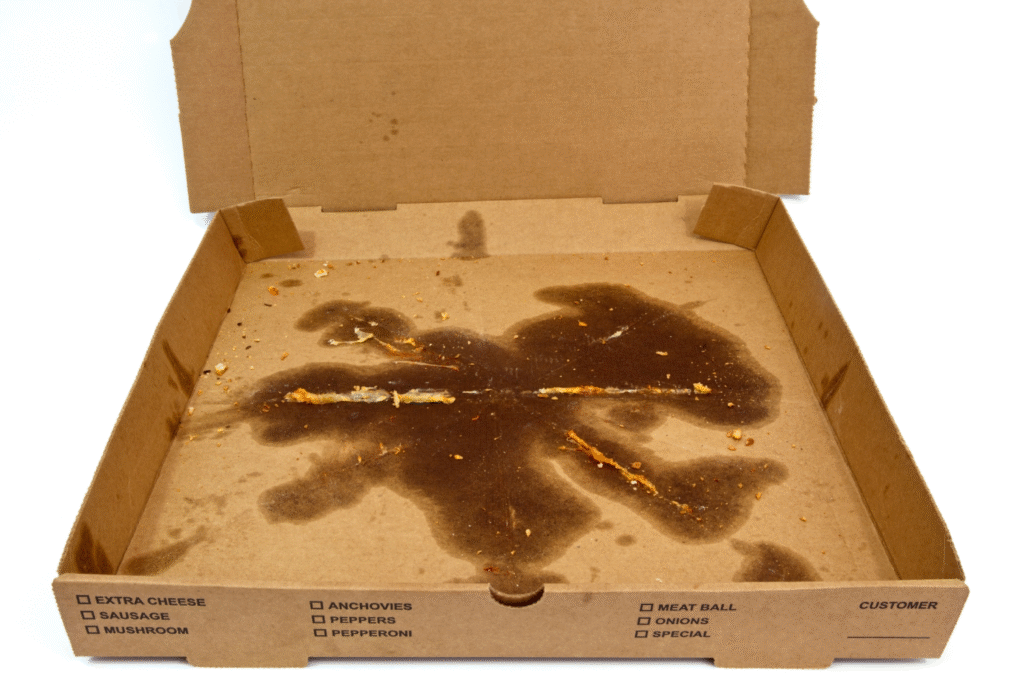

1. Pizza boxes soaked with grease are landfill-bound.

On the surface, a cardboard pizza box seems like textbook recycling. But grease and leftover food seep into the fibers, turning a recyclable item into contamination. Recycling facilities can’t process oily cardboard because the fibers won’t bond during pulping. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, these greasy boxes often divert entire loads of cardboard into the trash. Families tossing them in the bin may feel like they’re helping, but instead, the effort backfires. The residue doesn’t just ruin one box—it undermines the system that counts on clean paper.

2. Plastic bags slip through machinery and choke the system.

Those flimsy shopping bags feel like plastic that should be recyclable, but most curbside programs can’t accept them. They tangle around sorting equipment, forcing workers to shut down operations to cut them out. This isn’t just inefficient; it’s dangerous for workers too. Municipal recycling programs report that entire truckloads can be contaminated because of these bags, leading directly to the landfill instead of reuse, as discovered by the Recycling Partnership. The irony is that while these bags technically can be recycled, the only safe route is special drop-off bins at grocery stores.

3. Coffee cups hide a plastic secret under the paper.

That morning latte comes in what looks like a paper cup, but appearances deceive. Most disposable coffee cups are lined with polyethylene, a thin layer of plastic that keeps liquid from seeping out. As stated by the National Waste & Recycling Association, this lining makes cups almost impossible to process in standard recycling systems. The equipment is designed for paper or plastic—not hybrid products glued together. Millions of cups end up in landfills each day, despite being tossed in blue bins with good intentions. And while lids and sleeves can often be recycled, the cup itself rarely makes it through.

4. Shiny wrapping paper belongs in the trash.

Gift wrap glitters, shimmers, and gleams, but that very sparkle hides a problem. Many of those rolls are laminated with plastic or foil, which recycling facilities can’t separate from the paper. Add in tape and glitter, and the contamination spreads quickly. Families carefully folding leftover wrapping paper into the bin aren’t recycling—they’re just relocating the problem. The appearance of paper disguises its true complexity, leading to whole batches being discarded. Each holiday season, the damage is multiplied, an invisible cost of celebrations that feels harmless until it piles up.

5. Black plastic containers fly under the radar.

Supermarkets love packaging ready-made meals in sleek black plastic trays, but those trays pose a huge issue. Optical scanners at sorting facilities can’t detect the pigment, which means the containers aren’t recognized as recyclable. They pass straight through, ultimately joining the landfill waste stream. The packaging looks uniform and practical, yet the color alone determines its fate. This is a silent example of how design choices at the corporate level ripple into household recycling bins, leaving consumers with little control over the outcome.

6. Takeout clamshells confuse the system.

Clear, hinged clamshell containers made from PET plastic look identical to water bottles. But the plastics are manufactured differently, and in many recycling centers, clamshells contaminate the PET stream. Sorting errors multiply when these containers are thrown in with bottles, forcing facilities to toss them out altogether. They’re light, flimsy, and widespread, making the contamination issue significant. Every takeout dinner packaged this way extends the cycle of confusion, where items that appear recyclable quietly undermine the overall process.

7. Styrofoam doesn’t make the cut.

Polystyrene foam shows up in everything from coffee cups to packing peanuts. The problem is scale and economics: recycling Styrofoam isn’t practical because it’s bulky but low in value. Facilities can’t justify dedicating space to something with almost no resale market. Even when local collection is offered, it often ends up downcycled or discarded. Consumers are left in a cycle of good intentions, dropping foam in bins, while the end result rarely matches the hope. Styrofoam illustrates how market forces, not just materials, dictate what’s actually recyclable.

8. Plastic straws and utensils slip through undetected.

These items are too small and lightweight to make it through the sorting process. They fall between conveyor belts, evade scanning systems, and often mix with contaminants. Instead of becoming recycled plastic, they contaminate paper streams or go straight to landfills. They’re common, everyday items, and their scale makes the impact larger than most realize. Each straw or fork feels like a speck, but combined, the effect is enormous. The perception of recyclability collides with the reality of infrastructure limitations.

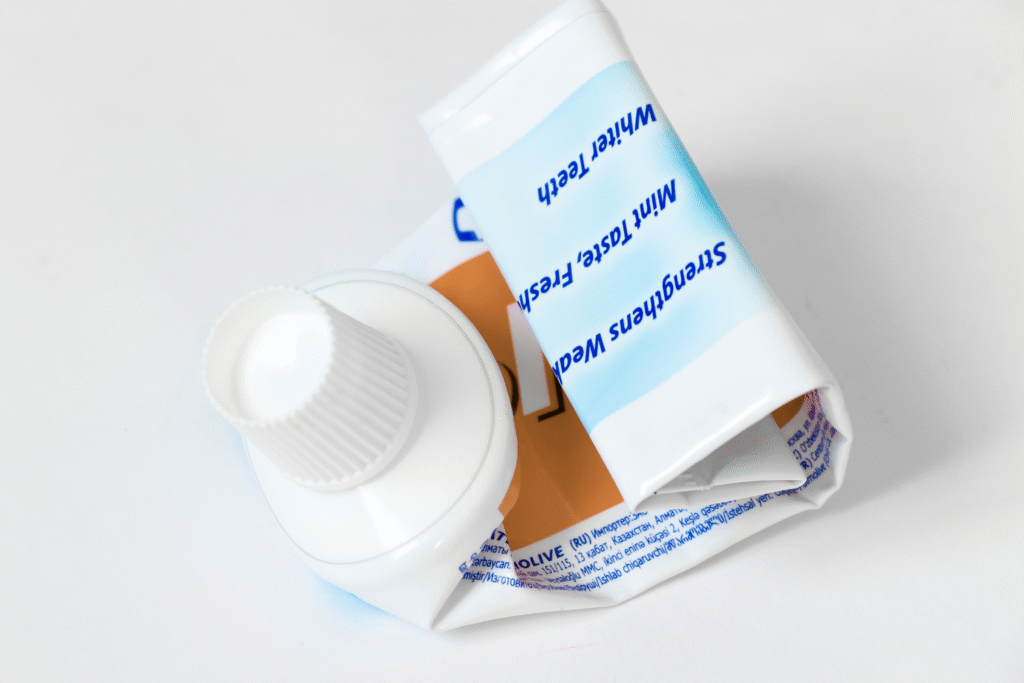

9. Toothpaste tubes carry hidden layers.

Squeezing the last drop of paste feels satisfying, but tossing the tube into the recycling bin doesn’t. Most toothpaste tubes are made from a laminate of plastic and aluminum, a layered material that machines can’t separate. They may look like straightforward plastic, but they’re not. Sorting facilities reject them, and they end up in trash streams. Companies are experimenting with single-material tubes, but the shift is slow. Meanwhile, consumers continue to feed an endless cycle of non-recyclable tubes into bins designed to handle something else.

10. Frozen food boxes resist recycling.

The box holding frozen pizza or vegetables may look like standard cardboard, but it’s treated with a chemical coating to resist moisture. That coating prevents it from breaking down during pulping, making it non-recyclable. Families tossing these boxes into bins assume the paperboard is harmless, but the lining changes everything. Like coffee cups, they’re designed for durability, not for reuse. The layers of invisible coatings hide the truth, leading to widespread contamination that slips by unnoticed in most households.

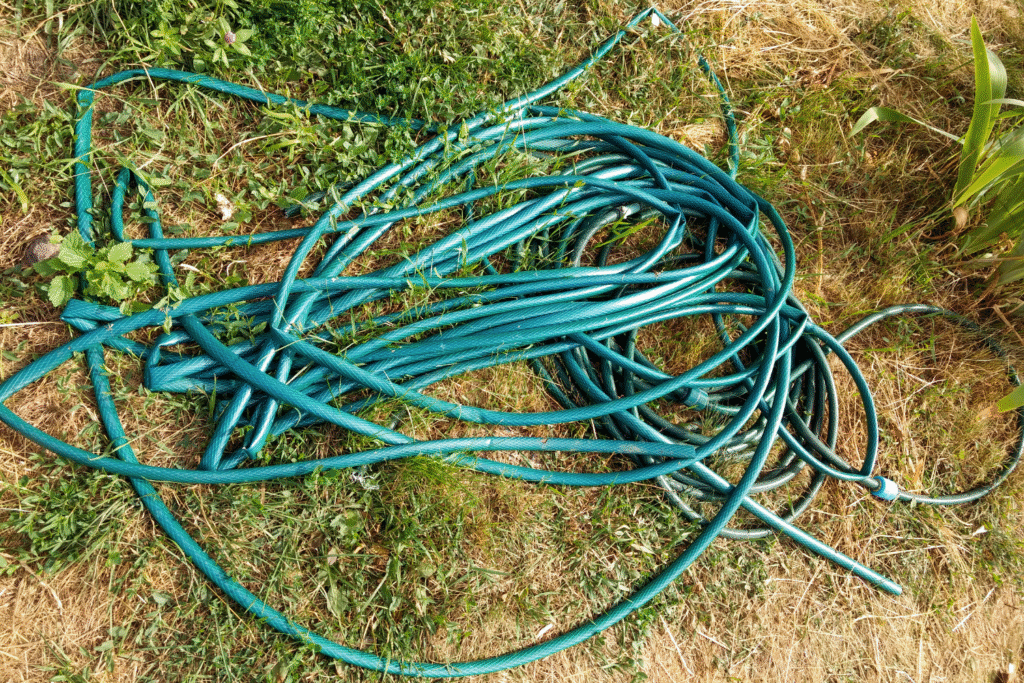

11. Garden hoses wreak havoc when tossed in bins.

It’s hard to imagine a garden hose as recycling contamination, yet it’s a nightmare for facilities. When coiled hoses hit conveyor belts, they tangle with machinery, creating shutdowns and damaging equipment. Workers call them “tanglers,” a category that includes extension cords and holiday lights. The damage is costly and dangerous, yet many people assume the rubbery plastic belongs in recycling. What feels like an innocent mistake in the backyard becomes a facility-wide disaster, another case where survival for the system depends on better household habits.