A surge in unregulated mining has unleashed toxic fallout across entire regions.

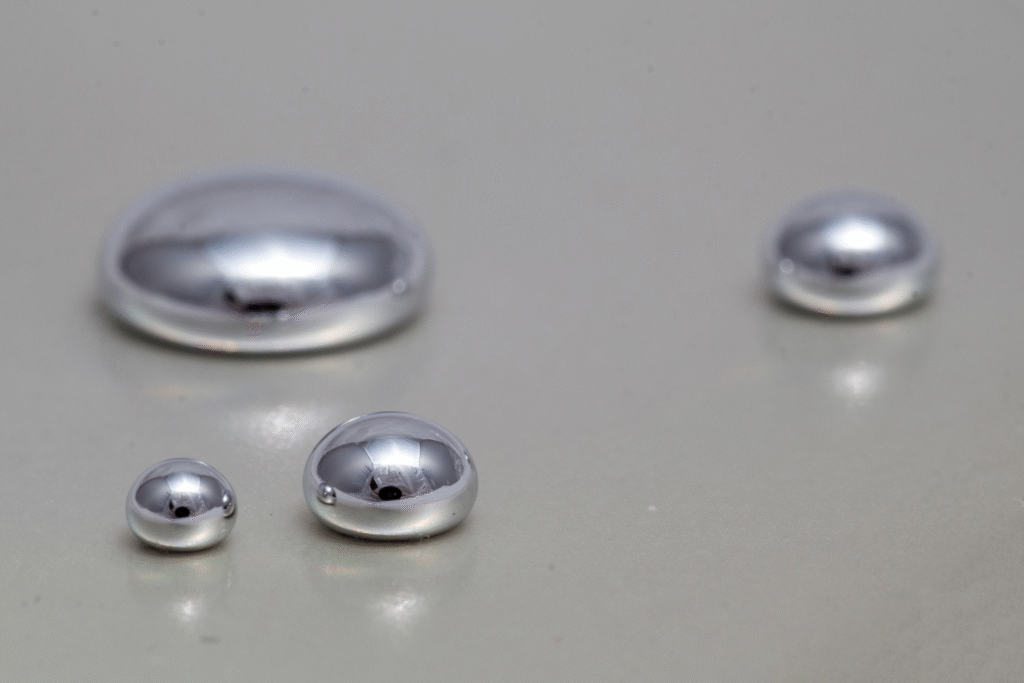

Rising gold prices have fueled a rush of illegal mining operations across Mexico, and with them comes a hidden contaminant—mercury. The toxic metal is used to extract gold from ore, but once released into rivers and soils, it spreads far beyond mining pits. Communities, wildlife, and even distant food chains are now absorbing the costs.

Scientists and activists warn that the scale of mercury pollution rivals some of the country’s most urgent environmental crises. From the Sierra Madre mountains to river valleys downstream, mercury contamination is leaving a signature in fish, farmland, and human blood samples. The boom may be enriching cartels and small operators, but it is also spreading poison in ways that will last for generations.

1. Mercury has become the unspoken cost of illegal gold mining.

Researchers at Mexico’s National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change have traced a sharp rise in mercury use to the surge in clandestine mining. Small-scale operations rely on mercury because it’s cheap and effective at binding gold, even though its environmental toll is staggering. Once released, mercury doesn’t vanish—it cycles between air, soil, and water, as reported by the institute.

That persistence means every ton used today becomes a problem tomorrow. Villages near mines face immediate exposure, but contamination also drifts across ecosystems. The more gold is dug from riverbeds, the more mercury embeds itself in Mexico’s landscapes.

2. Communities are finding mercury in their own bodies.

Health surveys conducted in Guerrero and Zacatecas have revealed mercury levels in residents that exceed World Health Organization safety thresholds. Mercury builds up in the nervous system, damaging coordination, memory, and even childhood development. The disturbing part is that many of those tested weren’t miners—they were simply people living near rivers and farmland downstream. These findings were documented in recent medical assessments, ending the sentence with WHO data.

Families discover the impact years later when chronic illness or developmental delays appear. Unlike other pollutants, mercury doesn’t just leave the body—it lingers. That makes today’s exposure a long-term health legacy.

3. Wildlife is becoming an invisible casualty of the boom.

Environmental groups monitoring rivers in Michoacán and Oaxaca have found mercury accumulation in fish and birds. Apex predators like herons and otters show especially high levels, signaling contamination has moved up food chains. As discovered by Conservation International, mercury doesn’t stay local. It magnifies at every step, from algae to fish to top predators.

This ripple effect means mercury pollution undermines biodiversity far beyond mining sites. Even species critical to ecotourism and local identity are at risk. What begins with a single vial of mercury in a gold pan can transform into a regional collapse of ecosystems.

4. Cartels have inserted themselves into the trade.

Illegal gold mining isn’t just small-scale—it’s lucrative enough to attract organized crime. In states like Guerrero, drug cartels have shifted into gold extraction, profiting from both the metal and the control of mercury supplies. This criminal involvement makes enforcement dangerous, leaving communities trapped between economic dependence and environmental collapse.

For authorities, targeting illegal mines means confronting groups far more violent than small prospectors. That entanglement complicates clean-up and oversight, ensuring mercury use continues with little accountability.

5. Rivers are carrying mercury far downstream.

Mercury isn’t contained by geography. Heavy rains wash residues into tributaries that feed larger rivers, which in turn supply cities with water and irrigate farmland. Crops grown in contaminated zones can absorb traces, extending exposure from fish to vegetables.

Urban centers hundreds of miles away may never see a mine, but they feel its consequences through food and water. This mobility makes mercury a national crisis, not a local one.

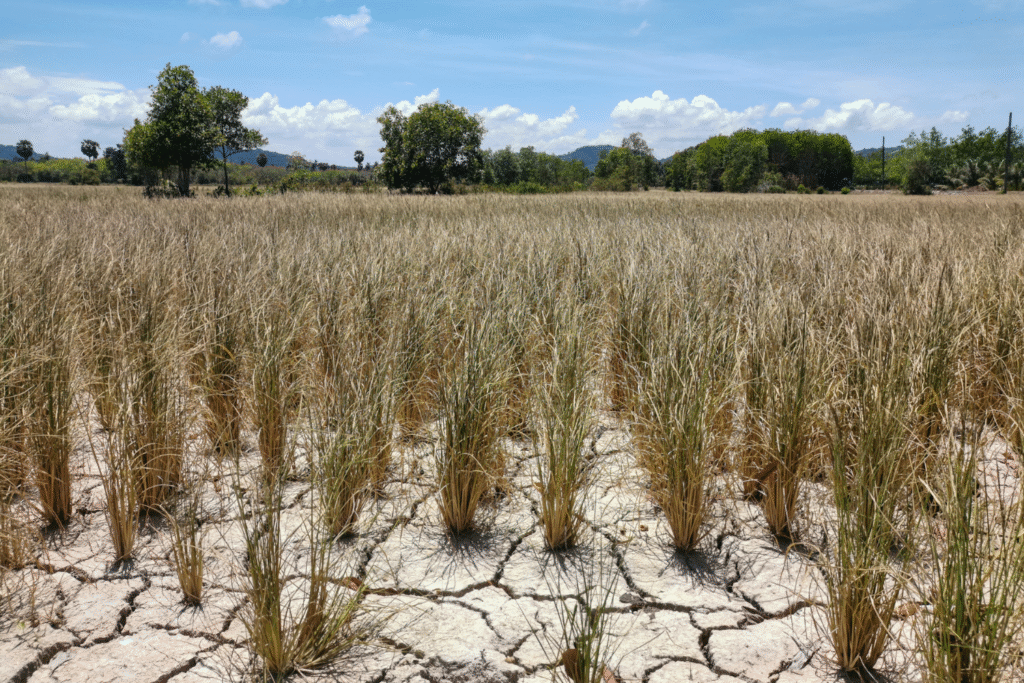

6. Farmers are caught in the crossfire.

Rural agricultural communities find their fields competing with illegal pits. As miners redirect streams and contaminate soils, crop yields decline. Farmers often face the impossible choice of selling damaged produce or abandoning land entirely.

This dynamic pushes some residents into mining themselves, perpetuating the cycle. Once traditional farming economies give way to gold extraction, mercury dependency deepens. The crisis is economic as much as ecological.

7. Enforcement is limited and often symbolic.

Mexico has laws regulating mercury imports and use, but enforcement struggles against both corruption and violence. Inspections are rare, and seizures barely dent the volume moving through illegal supply chains.

For local residents, this absence of accountability reinforces the feeling that mining will proceed unchecked. Without stronger monitoring and protection, laws remain words on paper while mercury continues to pour into rivers.

8. The gold trade links local contamination to global markets.

Illegal gold doesn’t stay in Mexico. Smugglers move it through refineries abroad, where it enters international markets indistinguishable from legally mined gold. Consumers buying jewelry in New York or Zurich may unknowingly be supporting mercury-laced mining in Mexico.

This global linkage spreads responsibility far beyond national borders. Addressing mercury pollution means not only cleaning up rivers but also tightening supply chains worldwide.

9. Health care systems are already overwhelmed.

Doctors in rural clinics often lack the resources to diagnose mercury poisoning, mistaking symptoms for malnutrition or other chronic illnesses. With few specialists available, long-term impacts go underreported and untreated.

This silence hides the true scope of the crisis. Without accurate diagnoses, families struggle without answers, while officials underestimate the scale of contamination. The health system itself becomes another casualty of the mining boom.

10. The toxic legacy will outlast the gold rush.

Mercury persists for decades, embedding itself in sediments and cycling through air and water. Even if illegal mining slowed tomorrow, the contamination already in place would continue affecting generations.

That permanence shifts the crisis from short-term pollution to long-term survival. What’s being unleashed now isn’t just a mining problem—it’s a public health and ecological burden that Mexico will carry long after the last gold nugget is dug from the ground.