Przewalski’s horses now roam Spanish highlands in an ambitious rewilding project that could reshape the landscape.

For the first time in more than 10,000 years, wild horses thunder across the highlands of central Spain, their hooves pounding the same earth where their ancestors once grazed. These aren’t feral horses or escaped domesticated animals, but the world’s last truly wild horses, brought back to fulfill their ancient ecological role.

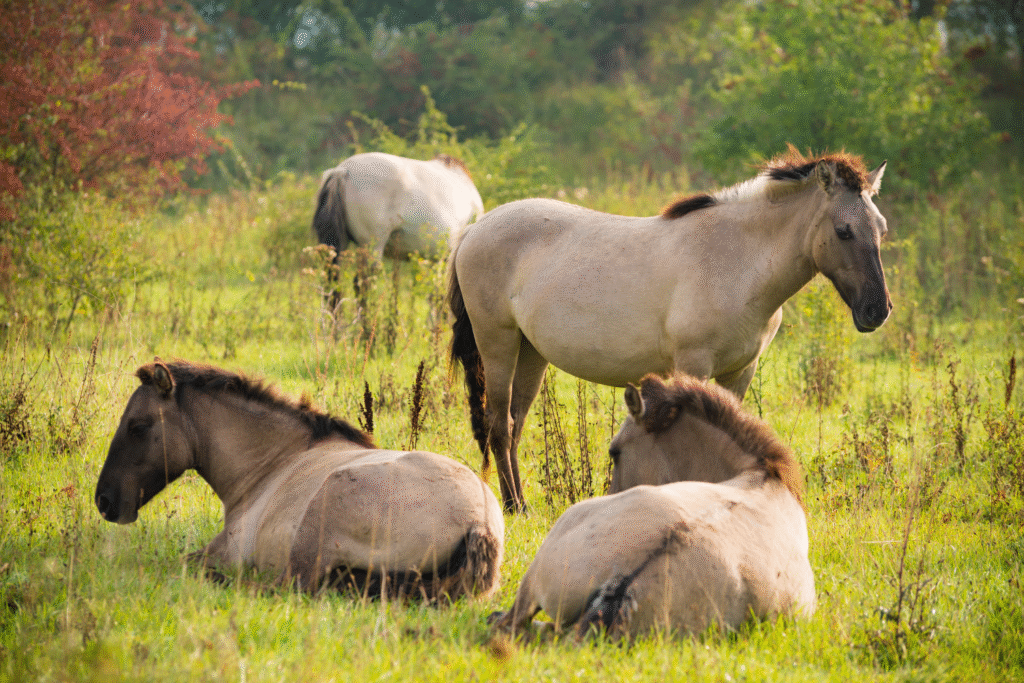

The sight is both remarkable and surreal: stocky, tan-colored horses with zebra-like manes galloping through Mediterranean oak forests, their GPS collars the only sign they live in the modern world. Their return marks one of Europe’s most ambitious rewilding efforts, designed to restore not just biodiversity but entire ecosystem functions lost for millennia.

1. Stone Age cave paintings reveal horses dominated ancient Spanish landscapes.

The limestone walls of Cueva de los Casares, carved by humans 30,000 years ago, tell an extraordinary story through dozens of wild horse images. According to researchers studying the cave art, wild horses were the most frequently depicted animals, appearing far more often than any other species in these prehistoric galleries. The detailed engravings show horses in various poses, from grazing to galloping, suggesting they were intimately familiar to the artists who created them.

These ancient testimonies prove that horses weren’t just visitors to the Iberian Peninsula but dominant members of the ecosystem. The cave paintings span thousands of years, indicating that wild horse populations thrived here through multiple climate changes and human cultures, making their eventual disappearance all the more profound.

2. Przewalski’s horses represent humanity’s last connection to truly wild equines.

Unlike mustangs or other feral horses that descended from domesticated stock, Przewalski’s horses never submitted to human control. Their genetic makeup differs fundamentally from domestic horses, possessing 66 chromosomes compared to the domestic horse’s 64, and DNA analysis reveals their evolutionary paths diverged between 160,000 and 38,000 years ago, as reported by conservation geneticists working with breeding programs worldwide. This makes them the sole surviving wild horse subspecies on Earth.

Named after Russian explorer Nikolay Przewalski who first described them scientifically in 1879, these horses survived in the steppes of Mongolia while their European cousins vanished. Their stocky build, erect black manes, and buckskin coloring represent what wild horses looked like before humans began selectively breeding for size, speed, and color variations.

3. Rural abandonment created the perfect opportunity for ecological restoration.

The mountains of Guadalajara province, where the horses now roam, represent España vacía, or “Empty Spain,” a region that has lost 80 percent of its population since 1950. As reported by demographic researchers studying Spanish rural decline, this area now has population densities similar to Siberia, with entire villages abandoned and agricultural lands reverting to scrubland. The exodus created an unexpected conservation opportunity.

Without traditional grazing by cattle and sheep, the landscape became choked with highly flammable vegetation, increasing wildfire risk dramatically. The absence of large herbivores allowed shrublands to dominate areas that historically supported diverse grasslands and open woodlands, creating conditions perfect for catastrophic blazes like the devastating 2005 fire that killed eleven firefighters.

4. Rewilding Spain assembled horses from European breeding programs.

The horses currently roaming Spanish forests came from two primary sources: the first ten arrived from Monts d’Azur Biological Reserve in France in May 2023, followed by sixteen more from Hungary’s Hortobágy National Park later that year. These breeding facilities maintain genetically diverse populations specifically for reintroduction projects, serving as modern arks for a species that nearly vanished forever.

All current Przewalski’s horses descend from just twelve individuals captured in the early 1900s, making genetic management crucial for species survival. The Spanish population represents carefully selected bloodlines designed to maximize genetic diversity while ensuring the horses can adapt to Mediterranean conditions rather than their native Mongolian steppes.

5. GPS collars reveal how horses reshape landscapes through grazing patterns.

Manuel Villa, the project’s herd manager, tracks the horses’ movements through GPS collars fitted to key individuals, discovering that they create mosaic grazing patterns fundamentally different from cattle or sheep. The horses preferentially consume tall, coarse grasses that other animals avoid, opening up dense vegetation to create natural firebreaks while allowing diverse wildflowers and herbs to flourish underneath.

Their selective grazing behavior creates heterogeneous landscapes with patches of short grass, tall grass, and scattered trees, providing habitat diversity that supports everything from ground-nesting birds to browsing deer. The horses’ dust wallows and rolling areas create microsites that benefit specialized plants and insects, demonstrating how large herbivores function as ecosystem engineers.

6. Fire prevention drives much of the rewilding project’s urgency.

Climate change has dramatically increased wildfire risk across Mediterranean Spain, with devastating blazes becoming annual occurrences. The 2005 Guadalajara fire burned 32,000 acres and created the political will for landscape-scale interventions to prevent future tragedies. The horses’ grazing reduces the continuity of flammable vegetation, creating natural firebreaks that slow fire spread and reduce intensity.

Unlike mechanical brush clearing, which requires constant maintenance and creates artificial-looking landscapes, horse grazing produces natural fire-resistant mosaics that sustain themselves through ecological processes. The animals work year-round, continuously managing vegetation loads while supporting biodiversity in ways that benefit the entire ecosystem.

7. Local communities transformed skepticism into economic opportunity.

Initially, some residents questioned bringing “foreign” animals to their traditional landscapes, but attitudes shifted as economic benefits became apparent. Pablo Villa, a lifelong horse enthusiast who left Villanueva de Alcorón thirty years ago when agriculture became unprofitable, returned to manage the herd, bringing his family back to a region they had abandoned.

The mayor reports that nature tourists now visit specifically to see the horses, supporting local restaurants and hotels while creating employment opportunities in guide services and environmental education. The project has directly created jobs for local residents while generating secondary economic benefits through eco-tourism, offering a sustainable alternative to traditional agriculture in marginal lands.

8. Genetic rescue efforts address the species’ narrow bottleneck.

The Spanish horses participate in a Europe-wide breeding network designed to prevent inbreeding and maintain genetic health across small, scattered populations. Regular exchanges between facilities in France, Hungary, Germany, and now Spain ensure genetic flow while building resilience against disease outbreaks or climate disasters that could eliminate entire populations.

Scientists hope eventually to reintroduce genetic material from Kurt, a Przewalski’s horse preserved as frozen cells whose DNA shows he lived before the population bottleneck occurred. This genetic rescue approach could restore lost diversity to help the species adapt to changing environmental conditions and expand beyond their current precarious numbers.

9. The project aims to rewild over two million acres across central Spain.

Current grazing rights cover 57,000 acres, but Rewilding Spain’s ultimate vision extends to 2.1 million acres across the Iberian highlands, creating one of Europe’s largest rewilded landscapes. The ambitious scope would connect fragmented habitats while supporting viable populations of multiple large herbivore species, from horses and cattle to eventually reintroduced lynx and wolves.

This landscape-scale approach recognizes that meaningful ecological restoration requires space for natural processes to operate without constant human intervention. The horses represent just one element of a broader strategy to restore the complex web of interactions between predators, prey, scavengers, and ecosystem engineers that shaped European landscapes for millennia.

10. Success could inspire rewilding movements across the Mediterranean.

The Spanish project serves as a testing ground for whether Przewalski’s horses can adapt to Mediterranean conditions far from their Mongolian origins, potentially opening new habitats for the species across southern Europe. Early results suggest remarkable adaptability, with horses thriving in oak forests and adjusting their grazing patterns to local vegetation cycles.

If successful, the model could be replicated across abandoned rural areas throughout Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece, where similar demographic and ecological conditions create opportunities for large-scale restoration. The horses’ return to Spain after 10,000 years may herald the beginning of a new chapter in European conservation, where ancient species reclaim their rightful place in landscapes shaped by both humans and wild nature.Retry