Trees underwater became gold mines for fishing families.

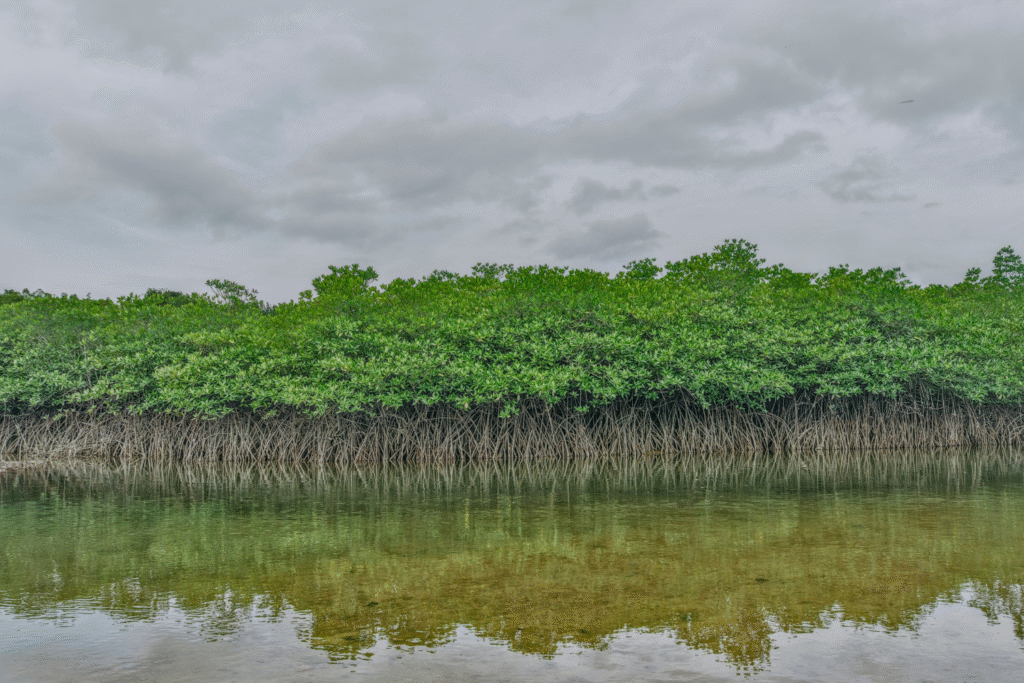

Picture an entire fishing community watching their livelihood disappear into murky, lifeless water. That’s exactly what happened along Mexico’s Pacific coast when decades of shrimp farming and coastal development destroyed thousands of acres of mangrove forests. The twisted, salt-tolerant trees that looked like nature’s afterthought turned out to be the foundation of everything. When the mangroves vanished, so did the shrimp, the fish, and the economic backbone of communities that had thrived on these resources for generations. But then something remarkable happened. Local fishermen, scientists, and government officials figured out how to bring it all back by replanting the very trees they’d once considered worthless obstacles to development.

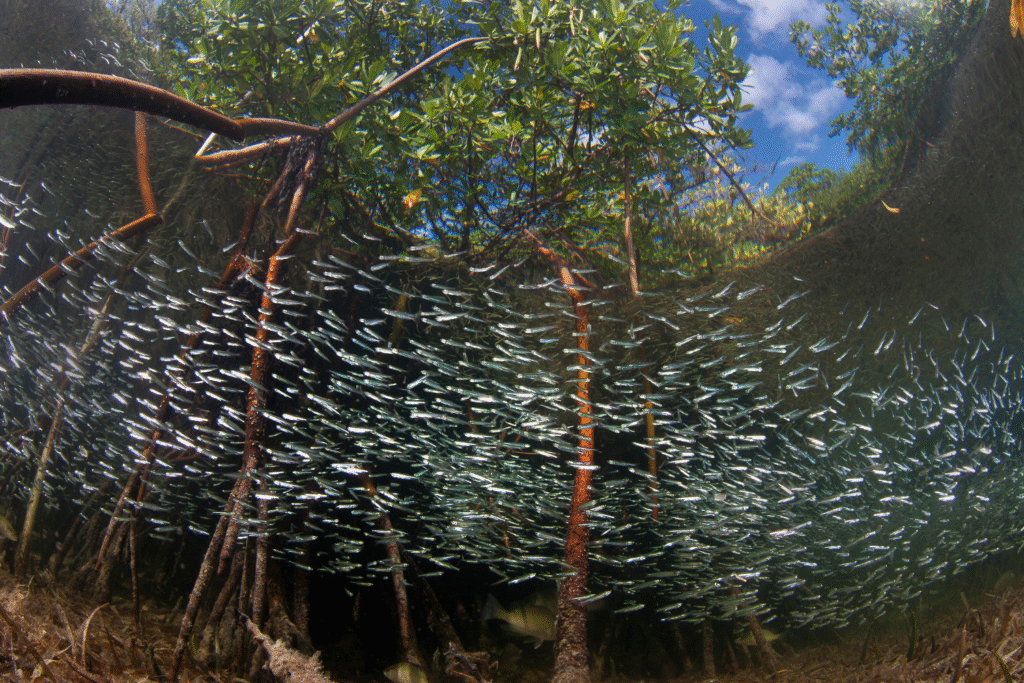

1. Nursery habitats returned when mangrove roots spread underwater.

Mangrove root systems create the ultimate underwater nursery, providing shelter and food for juvenile shrimp during their most vulnerable life stages. These complex root networks offer protection from predators while filtering nutrients that support the microscopic organisms baby shrimp need to survive. According to research published by the Mexican National Institute of Fisheries, restored mangrove areas showed a 340% increase in juvenile shrimp populations within three years of replanting.

The intricate root maze acts like an underwater apartment complex where young shrimp can hide, feed, and grow before venturing into open waters. Without this protected nursery habitat, shrimp populations crash because juveniles face impossible survival odds in exposed coastal waters. Restoration projects that focused on recreating these root systems saw the fastest recovery of shrimp populations.

2. Water filtration improved dramatically after replanting began systematically.

Mangrove trees function as natural water treatment plants, their roots and associated microorganisms filtering pollutants, excess nutrients, and sediments from coastal waters. The filtration process creates the clear, oxygen-rich conditions that healthy shrimp populations require for reproduction and growth. Restored areas showed measurable improvements in water quality within 18 months, with nitrogen levels dropping by 60% and dissolved oxygen increasing by 45%, as reported by Mexico’s Environmental Protection Agency.

Cleaner water doesn’t just benefit shrimp. The improved conditions support entire food webs that had collapsed when pollution and sedimentation made coastal areas uninhabitable for most marine species. Fishermen noticed that not only were shrimp returning, but dozens of fish species that hadn’t been seen in years were reappearing in areas with restored mangroves.

3. Storm surge protection saved fishing boats and coastal homes.

Mangrove forests act as natural seawalls, their dense root systems and flexible branches absorbing wave energy and reducing coastal erosion during storms. Communities that had lost their protective mangrove barriers found themselves increasingly vulnerable to hurricane damage and coastal flooding. Restoration efforts prioritized areas where fishing families lived and stored their boats, recognizing that economic recovery depended on protecting both the ecosystems and the infrastructure that supported local fisheries, as discovered by researchers studying coastal resilience in Sinaloa state.

The economic benefits became obvious during the first major storm after restoration began. Fishing communities with restored mangrove protection reported 70% less property damage compared to areas that remained unprotected. Boats that would have been destroyed or severely damaged survived storms that previously would have wiped out entire fishing fleets.

4. Local employment expanded beyond traditional fishing methods.

Mangrove restoration created entirely new job categories in communities that had few economic alternatives to fishing. Local residents became expert tree planters, nursery operators, and ecosystem monitors, developing specialized skills that complemented rather than replaced traditional fishing knowledge. The restoration work provided steady income during fishing off-seasons and bad weather periods when boats couldn’t operate safely.

Women in fishing families found particular opportunities in mangrove restoration, often taking leadership roles in nursery operations and community education programs. These jobs offered more predictable schedules and working conditions than the traditionally male-dominated fishing industry. Many families discovered that combining fishing with restoration work provided more economic stability than relying on fishing alone.

5. Ecotourism revenue emerged from restored mangrove corridors.

Tourist boats began appearing as restored mangroves created spectacular wildlife viewing opportunities that hadn’t existed for decades. Bird populations exploded in the recovering forests, attracting birdwatchers and nature photographers willing to pay for guided tours through the restored ecosystems. Local fishing guides discovered they could earn more money showing tourists around mangrove channels than they made from traditional fishing trips.

The tourism development happened organically as word spread about the dramatic ecosystem recovery. Fishing families who had lost income from declining shrimp catches found themselves earning money from visitors who wanted to see the restoration success story firsthand. Hotels and restaurants in nearby towns began promoting mangrove tours as signature attractions.

6. Carbon credit sales generated unexpected income streams.

Mangrove forests store more carbon per acre than almost any other ecosystem on Earth, making restored areas valuable for carbon offset programs. Communities that had never heard of carbon credits suddenly found themselves earning money for the climate benefits their restoration work provided. International companies and governments began paying local communities for the carbon storage services their restored mangroves delivered.

The carbon payments created long-term financial incentives for maintaining and expanding restoration efforts. Unlike fishing income that fluctuated with market prices and weather conditions, carbon credit payments provided predictable annual revenue based on forest health and growth. Communities realized they could earn more from preserving mangroves than from clearing them for development.

7. Shrimp aquaculture operations adopted sustainable mangrove integration practices.

Former enemies became unlikely allies as shrimp farmers discovered that integrating mangroves into their operations actually improved productivity and reduced costs. The trees provided natural water filtration, disease prevention, and habitat for wild species that supported healthier pond ecosystems. Progressive farm operators began designing new facilities that incorporated mangrove corridors rather than destroying existing forests.

The shift from conflict to collaboration transformed entire coastal regions. Shrimp farms that had once been seen as environmental destroyers became partners in restoration efforts, contributing funding and expertise to expand mangrove coverage. The integrated approach proved that aquaculture and ecosystem conservation could support rather than compete with each other.

8. Fish catches increased beyond shrimp to include multiple species.

Restored mangrove ecosystems supported complex food webs that benefited many more species than just shrimp. Fishermen who had specialized in shrimp began catching greater varieties of fish, crabs, and other seafood as the restored habitats attracted diverse marine life. The increased biodiversity provided economic insurance against the boom-and-bust cycles that had made shrimp-dependent communities so vulnerable.

Restaurants and seafood buyers began seeking out products from the restored areas, creating premium markets for sustainably caught seafood. Local fishing cooperatives developed certification programs that guaranteed their products came from restored mangrove ecosystems, allowing them to charge higher prices and access new markets.

9. Educational programs trained young people in restoration techniques.

Schools and community centers began offering courses in mangrove biology, restoration methods, and ecosystem monitoring, creating career pathways for young people who might otherwise have left their communities seeking economic opportunities elsewhere. The technical knowledge required for successful restoration elevated the status of environmental work in communities where education had been undervalued.

Young graduates of these programs became restoration specialists who could work on projects throughout Mexico and Central America. The expertise developed in these coastal communities became exportable, creating consulting opportunities and regional leadership roles for people who had grown up watching their local ecosystems collapse and recover.

10. Regional food security improved through diversified marine harvests.

Restored mangrove ecosystems provided communities with diverse, reliable food sources that reduced their dependence on external food systems and global market fluctuations. Families could supplement purchased foods with fish, shellfish, and other marine resources harvested sustainably from the recovering ecosystems. The food security benefits proved especially valuable during economic downturns and supply chain disruptions.

Traditional ecological knowledge combined with modern restoration science created management systems that maintained productivity while ensuring long-term ecosystem health. Communities developed harvesting rotations and seasonal restrictions based on species life cycles and habitat requirements. The restored mangroves became both economic engines and food security anchors for thousands of families who had once faced uncertain futures.