Her death leaves a legacy spanning science and humanity.

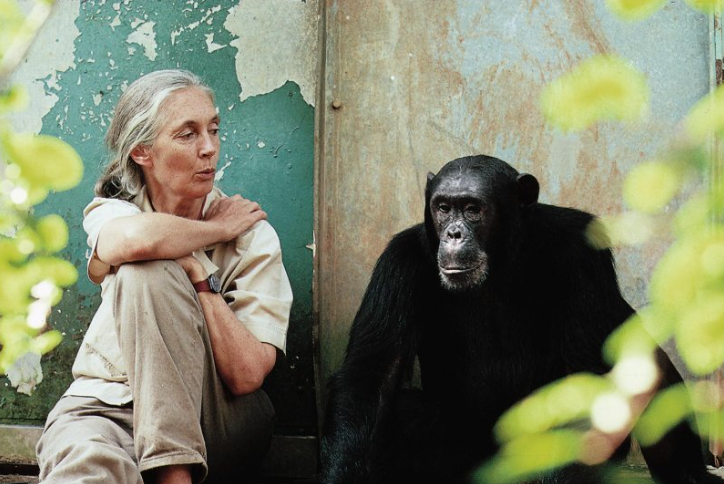

Jane Goodall’s passing at 91 has left the world reflecting on a lifetime devoted to understanding the natural world and protecting it. She became a household name not just for living among chimpanzees in the forests of Tanzania but for teaching us that animal behavior mirrors our own in profound ways. Her legacy stretches beyond science into activism, education, and global awareness. From the notebooks she carried into Gombe to the international institutes bearing her name, Goodall’s work continues to ripple through generations who learned to see animals as thinking, feeling beings.

1. A young woman entered Gombe against all odds.

Back in 1960, when Jane Goodall first set foot in Gombe, women were largely absent from frontline field research. With nothing but a notebook and a pair of binoculars, she immersed herself in a world no one had truly watched up close. According to National Geographic, her presence in Tanzania marked a groundbreaking moment for women in science, proving persistence mattered more than academic titles. Goodall’s choice wasn’t only about studying chimps; it was about showing that curiosity had no boundaries, including gender. From that forest edge, her story grew into a lesson in both courage and discovery.

2. Chimps were caught using tools for survival.

At first, scientists refused to believe chimpanzees were capable of crafting tools. Then came Goodall’s observations of chimps stripping leaves off twigs to fish termites from mounds. The discovery in 1960 challenged the very definition of humanity, since tool use was thought to be uniquely ours. As stated by the Smithsonian, her work forced anthropologists to rewrite textbooks and reconsider where humans sat in the natural order. It was not just about chimps using sticks—it was about humans realizing we were not as separate from nature as we once believed. That moment shifted the foundation of primate research.

3. Emotions were finally recognized in the animal kingdom.

While many researchers insisted on keeping animals at arm’s length, Goodall leaned in with empathy. She described individual chimpanzees with names, not numbers, and documented grief, playfulness, and even maternal tenderness. This approach humanized her subjects and sparked debates across scientific circles. As discovered by the American Psychological Association, her framing of chimps as emotional beings influenced how people viewed animal sentience far beyond primatology. That choice, once controversial, has since become central to conservation and animal welfare. From Gombe’s treetops to global classrooms, her work taught that emotion is not limited to the human heart.

4. Names replaced numbers in her radical approach.

Early in her career, colleagues scoffed at her practice of naming chimpanzees instead of numbering them. Yet Goodall believed that seeing David Greybeard or Flo as individuals created a deeper truth. This wasn’t sentimentality but an insistence that personality, intelligence, and social bonds mattered. That belief planted seeds for later conservation movements, where empathy drives action. Her refusal to conform showed that science could be rigorous without stripping away compassion. That balance still echoes in classrooms, labs, and sanctuaries, where animals are seen not just as data points but as lives worth knowing.

5. Violence among chimps shocked the scientific world.

Goodall’s observations were not always comforting. In the 1970s she documented the so-called “Gombe Chimpanzee War,” where groups of males fought brutally for territory and dominance. It shattered the idyllic image many held of primates as peaceful beings. What she recorded was complexity, alliances, betrayal, and cruelty alongside nurturing behavior. By exposing this darker side, she proved chimpanzee societies mirrored the contradictions in our own. These findings challenged researchers to accept that intelligence and compassion often coexist with aggression and power struggles, reshaping the broader conversation about human evolution and animal behavior.

6. Conservation turned into her life’s second chapter.

After decades in the forest, Goodall shifted focus to saving habitats threatened by logging, farming, and development. She recognized that watching chimpanzees meant nothing if their homes disappeared. By the mid-1980s, she was traveling nonstop, raising awareness about deforestation across Africa and beyond. This shift from research to activism widened her reach, drawing in audiences who might never have opened a scientific journal. Her voice carried urgency but also hope, pushing for both policy changes and grassroots education. In that transformation, she became not only a scientist but also a global advocate for the planet’s survival.

7. A global network of young activists grew from her vision.

Goodall didn’t just speak to world leaders—she spoke to children. In 1991, she founded Roots & Shoots, a youth program that began in Tanzania with a handful of students. It has since spread to more than 60 countries, connecting young people with projects in conservation, animal welfare, and humanitarian work. The brilliance of her model lay in its simplicity: empower kids to act locally while feeling part of something larger. For many students, the program served as their first invitation into activism. Through this, Goodall’s influence stretched into classrooms, playgrounds, and backyards across the world.

8. Her lectures became packed with standing-room-only crowds.

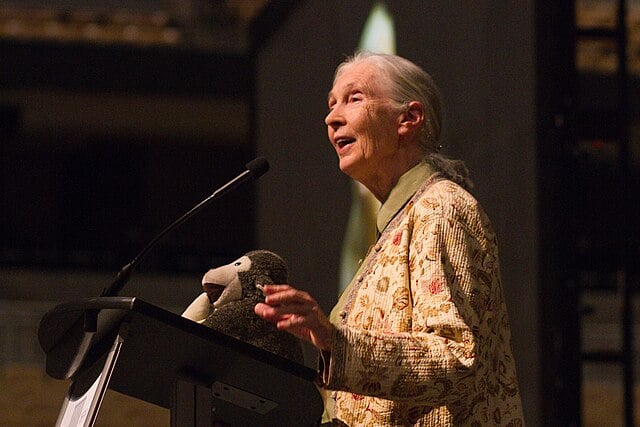

By the 1990s and 2000s, Goodall was less likely to be in Gombe and more likely on a stage. She carried stories of chimps and forests into auditoriums, speaking with a quiet intensity that made people lean in. Unlike many scientists, she wasn’t buried in jargon. Her style was conversational, like a friend explaining why the world mattered. Audiences often left inspired not just to donate but to change habits at home. Those talks—part storytelling, part call to action—turned Goodall into one of the most recognizable voices for conservation on the planet.

9. Honors and awards never defined her true legacy.

Though she collected accolades, the Kyoto Prize, the Templeton Prize, and even a Damehood, Goodall rarely spoke about them. For her, the real reward was progress in conservation and the spread of awareness. The awards often opened doors, giving her credibility in rooms where she might have otherwise been dismissed. Yet she consistently redirected attention to the issues rather than herself. In that way, her humility became as defining as her scientific discoveries. She modeled that recognition should be a tool, not a destination, reminding others where the spotlight truly belonged.

10. She bridged science and spirituality with unusual grace.

Goodall often spoke about the intersection of faith, awe, and nature. While trained in observation and data, she openly admitted that sitting quietly in the forest sometimes felt like prayer. To her, the wonder of watching a chimpanzee or hearing a bird call wasn’t just biology, it was connection. That ability to blend science with spirituality drew in audiences who might not normally follow research. It created a bridge where people of varied beliefs could meet. She made the point simple: protecting the Earth was not only rational but deeply spiritual work.

11. Media turned her life into a symbol of hope.

From early National Geographic documentaries to biographies and interviews, Goodall became an icon as much as a scientist. Seeing her kneeling among chimpanzees or scribbling in notebooks gave people an image of dedication they could hold onto. These portrayals elevated her beyond academia and into cultural memory. The constant media attention also had its risks, sometimes overshadowing the depth of her research. Yet she used that visibility wisely, always redirecting it toward causes rather than personal fame. By allowing cameras into her world, she opened millions of eyes to the urgency of conservation.

12. She never stopped traveling well into her eighties.

While many slowed down with age, Goodall kept an astonishing schedule of up to 300 days on the road each year. She spoke in packed schools, crowded lecture halls, and even small town meetings, spreading her message in places both grand and humble. The stamina was extraordinary, especially given the jet lag and the endless hotel rooms. What fueled her wasn’t obligation but belief that every conversation had the potential to spark change. Her energy became part of her legend, a reminder that age was no barrier when purpose ran deep.

13. The world remembers her as more than a scientist.

Goodall’s passing at 91 closes a remarkable chapter, but her legacy lives in countless ways: the forests she fought to save, the students she inspired, the chimps whose lives she documented. She was not just a scientist, not just a conservationist, not just a storyteller. She was a reminder that curiosity, empathy, and persistence can move the world. The mourning is global, but so is the gratitude. In every future act of conservation, her fingerprints will remain, guiding us to remember that humans are part of the natural story, not separate from it.