Mothers struggle when oceans warm too much.

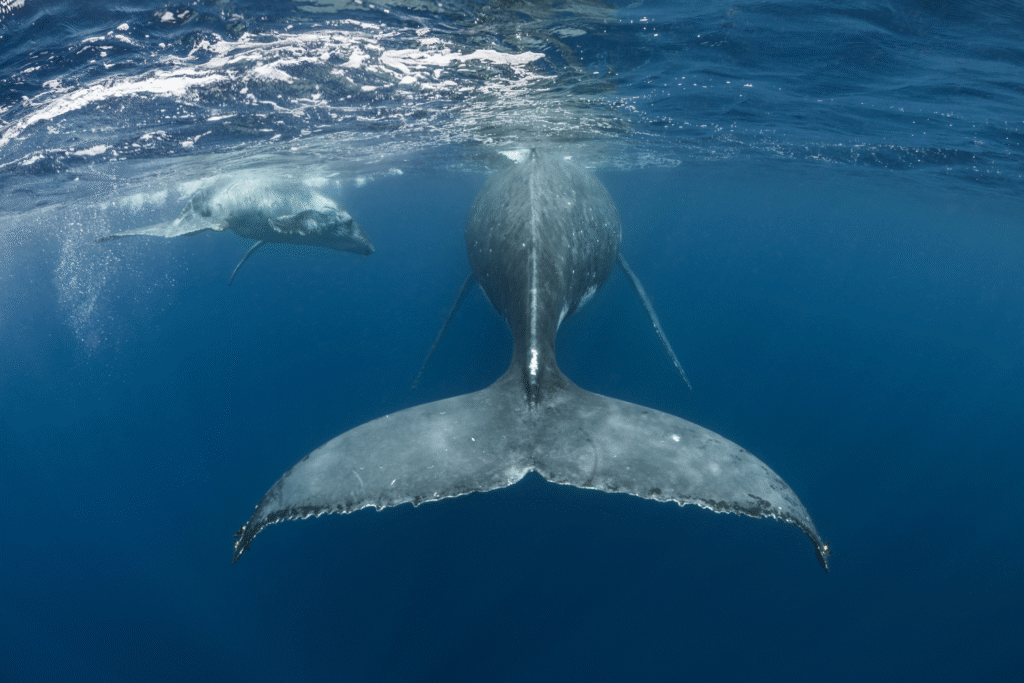

When seas warm, the food web changes — and that hits whale mothers hardest. As their prey becomes scarcer, pregnant and nursing females can’t get enough nutrition to feed themselves and their calves. The result: lower birth rates, weaker babies, even starvation.

This crisis is not hypothetical. In recent years researchers have documented rising starvation and mortality among whales, especially in populations whose feeding grounds have been altered by marine heatwaves or shifts in prey distribution. Below are ten ways this phenomenon shows up — and what the science is revealing.

1. Mothers lose weight before giving birth.

In some whale populations, females are arriving at breeding grounds noticeably leaner than expected. That suggests they are struggling to accumulate energy reserves during feeding seasons. Studies of humpback whales point to ecosystem disruption, caused by marine heatwaves that reduce plankton and krill abundance, as a culprit behind widespread decline in prey availability. The starvation hypothesis helps explain why many mothers cannot sustain healthy pregnancies, as reported by the Guardian’s recent coverage on whale mortality linked to warming seas.

Those energy deficits affect not just offspring but the mothers themselves, making them more vulnerable to disease and reducing their future reproductive capacity.

2. Calves receive insufficient milk and fail to thrive.

Because whales rely entirely on the mother’s fat and nutrition stored before birth, any deficit undermines lactation. Researchers have observed calves in certain populations that are underweight or showing signs of malnutrition. According to some analyses of whale strandings and necropsy results, starvation arising from food scarcity is a leading factor in calf mortality.

When mothers cannot maintain milk output, calves may weaken quickly, unable to swim strongly, evade predators, or compete for resources.

3. Starvation events correlate with marine heatwaves.

In the North Pacific, marine heatwaves from 2014 to 2016 severely disrupted nutrient upwelling. That reduced the base of the food web — plankton and small prey — eventually cascading upward and depriving humpback and other whale species of food. Researchers documented a roughly 20 percent decline in some humpback populations over that interval, linking warm oceans to higher mortality among whales.

This pattern offers a striking case of how climate anomalies destabilize marine mammals. Such connections underscore how sensitive whale reproduction is to broad-scale oceanographic shifts.

4. Reproductive rates plummet in stressed populations.

When mothers strain under nutritional stress, fewer pregnancies succeed. Populations already weakened by environmental change see a drop in calf births. Low reproductive output compounds the mortality problem, as fewer new whales enter the population.

Over time, this dynamic can tip a population into decline, because losses outpace births. A cascade begins: warming reduces prey, mothers starve, reproduction falters, calves die, and the population’s ability to bounce back weakens.

5. Migration routes shift toward better feeding zones.

Facing food scarcity in traditional feeding areas, whales may alter migratory patterns to chase prey. Some populations are showing signs of extended routes or new feeding grounds further north or deeper.

Such shifts often come with risks: unfamiliar terrain, increased energy expenditure during migration, and exposure to new predators or human threats like ship strikes. These costs further stress already vulnerable mothers and calves.

6. Mothers delay or skip reproduction altogether.

Whales may adopt a strategy of reproductive refusal when conditions are poor. A mother undernourished might not even attempt to conceive or may abort early. This self-protective biology preserves her survival but deprives the population of new individuals.

When large numbers of females adopt this strategy, population trajectories shift downward. Years of reduced reproduction set the stage for long-term decline.

7. Immune function and health degrade under stress.

Nutrition is foundational to immune responses. Starving mothers face compromised immunity, making them more susceptible to disease, parasites, or stress-induced mortality. The calves, too, inherit weakened defenses.

In stressed populations, pathology surveys have found more infections or poor condition in stranded whales. That suggests that starvation doesn’t just weaken reproduction — it erodes overall health resilience.

8. Behavioral conflicts over limited food intensify.

When prey becomes scarce, whales may compete more aggressively — moving closer to human-impacted zones, overlapping with fisheries, or entering riskier waters. This elevates the chance of entanglement, collisions, or exposure to pollutants.

Conflicts with fisheries increase, and competition may push some mothers into marginal feeding areas that are less optimal or riskier, further exacerbating nutritional stress.

9. Calf mortality spikes in heat-stressed years.

In years following strong marine heat anomalies, record numbers of stranded calves or orphaned juveniles have been documented. Those cohorts often include animals too weak to survive.

Such mortality events create gaps in population age structure, making recovery harder. The loss of entire calf year-classes leaves a demographic hole that can take decades to fill — if conditions improve.

10. Long-term population declines become more likely.

As these factors compound — fewer births, higher mortality, shifting migration, weakened health — the risk of sustained decline grows. Populations already endangered or with low numbers are at particular risk of local extinction.

Recovery under such pressure becomes slow, constrained by the very environmental changes that triggered decline. These patterns are sounding alarms among whale scientists and conservationists.

This emerging crisis reveals how intimately whale life cycles are tied to ocean health. When warming seas unravel prey webs, the cost is highest for mothers and calves — and the impacts echo across generations.