Many species lose habitat faster than they adapt.

In recent decades, scientists have documented how rapid climate change is shrinking safe zones for many plants and animals, pushing them into narrower ranges or driving them toward extinction. Warming, altered precipitation, sea level rise, and shifting seasons disrupt life cycles, food webs, and habitats in ways species often can’t keep pace with.

These pressures don’t affect all species equally. Some are more specialized, isolated, or slow to migrate, and they bear the brunt of change. Below are ten species or groups already showing signs of being forced from their historical ranges because of climate shifts.

1. American pika retreats upslope in mountains.

Lowland pika populations are vanishing as temperatures climb, leaving only high elevation refuges. Because American pikas can die within hours of exposure to heat above about 25.5 °C, researchers see lower elevation extirpations in many mountain ranges, and upslope contraction of their range has been documented. Their movement is constrained by terrain, making further upslope shifts impossible in many settings, as noted by studies of pika declines.

Faced with hotter summers and less snowpack insulation in winter, the remaining populations are squeezed into shrinking thermal niches. That contraction makes them more vulnerable to extreme weather, isolation, and local extinction.

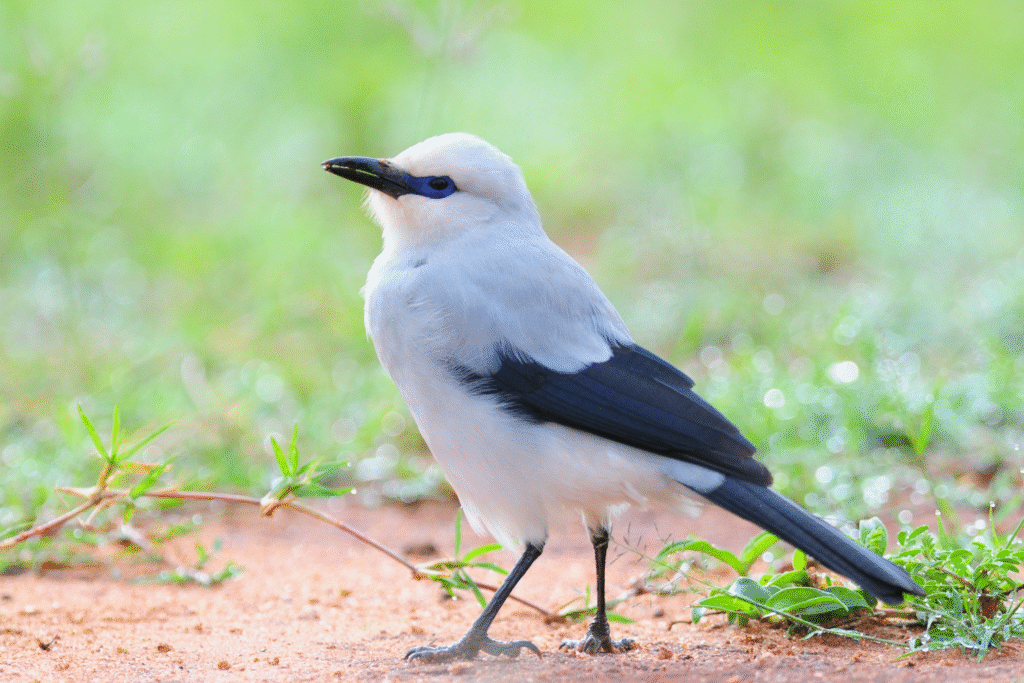

2. Stresemann’s bushcrow may lose 90 percent habitat.

This Ethiopian endemic bird occupies a narrow climate zone tied to specific temperature and humidity ranges, and climate models forecast that by 2070 its suitable habitat may shrink by 90 percent according to projections for its range. Populations already decline, and further warming threatens to render much of its current range uninhabitable.

As temperatures rise and rainfall patterns shift, the bird can’t simply move much farther; its niche is restricted by elevation and ecology. It faces a kind of climate trap—no new territory to colonize, just vanishing suitability.

3. Bramble Cay melomys was lost to sea level rise.

The Bramble Cay melomys, a small rodent on a low coral cay, lost its habitat through repeated inundation as sea levels rose and storm surges increased. That island was its only home, and its disappearance is now viewed as the first mammal extinction attributed to climate change, as reported by conservation assessments.

Once vegetation was destroyed by saltwater intrusion and habitat collapse, the rat lacked refuges. Its fate illustrates how species on small islands or low-elevation zones are particularly vulnerable when climate drives habitat loss without escape routes.

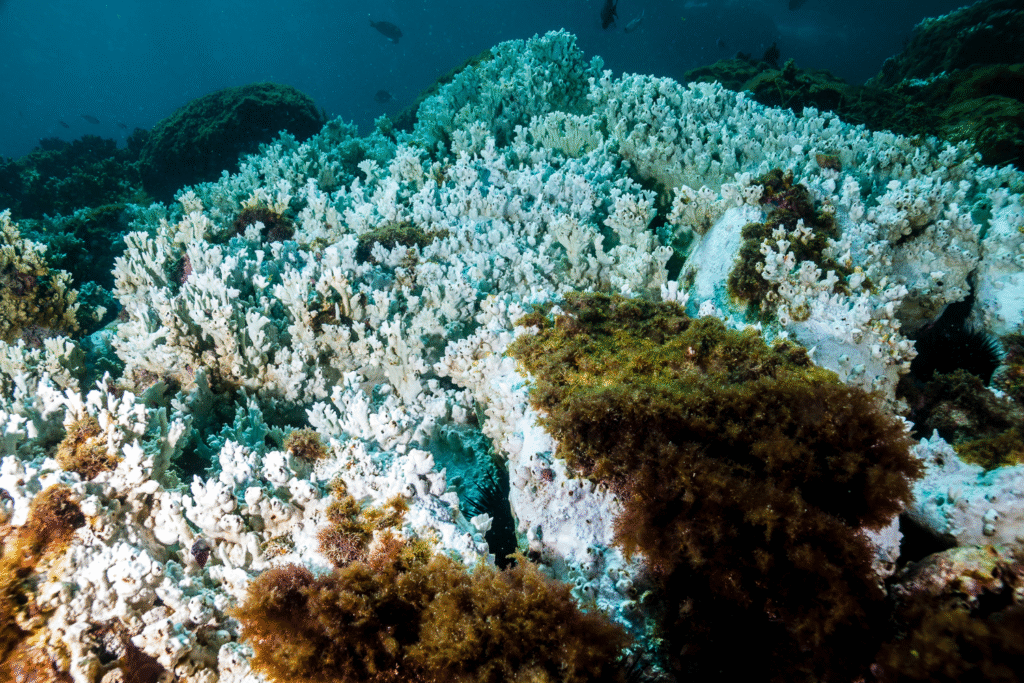

4. Coral species bleach and vanish from warming seas.

Many reef corals live close to their thermal tolerance limits. When oceans warm even a degree or two above local norms, corals expel their symbiotic algae, bleach bright white, and often die. Repeated or prolonged heating kills colonies, reducing reef coverage and forcing coral species to shrink into cooler, deeper, or higher-latitude waters.

This shift fractures reef ecosystems. Fish and invertebrates dependent on those corals find less habitat, triggering cascading losses. Some coral species decline so fast that they’d be functionally absent from vast stretches of tropical seas.

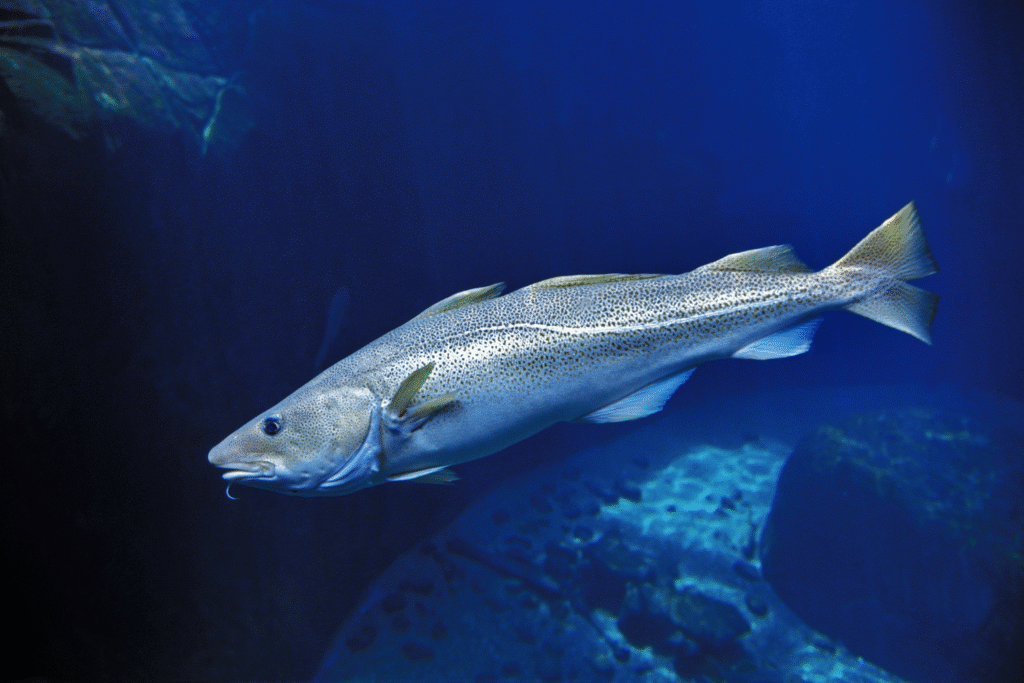

5. Atlantic cod shifts northward under warming oceans.

As sea surface temperatures rise, populations of Atlantic cod have retreated toward cooler northern waters. Their historical southern range is becoming inhospitable due to altered prey availability, warmer waters, and changed currents. The cod’s migration north imposes challenges for fisheries, ecosystems, and local human communities.

Because cod are adapted to specific temperature and salinity windows, they can’t thrive where warmth overwhelms their physiology. Their retreat reshuffles food webs, pushing predators or competitors into new zones.

6. Yellow cedar trees die back in Pacific Northwest.

In coastal Alaska and British Columbia, yellow cedar trees are dying across large swaths. Scientists link the decline to warmer winters, reduced snowpack, and greater soil freezing in winter — conditions that freeze roots and damage tree health. This dieback forces retreat of cedar forests into more limited ranges.

Because seedlings and young trees are especially vulnerable to freezing, regeneration fails in deteriorating zones. Over time, cedar populations contract away from zones with deeper snow insulation, leaving fragments in marginal surviving habitats.

7. Polar bears lose sea ice hunting grounds.

Polar bears rely on sea ice for hunting seals, mating, and traveling. As Arctic ice diminishes in extent and thickness, bears find fewer stable platforms to rest and hunt. Some populations have already shown declines and shifts in marking or movement patterns.

With shorter ice seasons, bears spend more time fasting on land, leading to weight loss, lower reproductive success, and increased human conflict as they wander inland. Their effective range is shrinking toward the high Arctic.

8. Sea turtles struggle with shrinking nesting shores.

Rising sea levels and coastal erosion are reducing and submerging nesting beaches for many sea turtle species. Beaches once safe from tides now flood during storms or high tides, washing away nests or drowning eggs. As coastlines shift, turtles must find new nesting sites or face reproductive failure.

Because nesting fidelity is strong (turtles often return to the same beach), they may attempt dangerous or unsuitable locations. Some populations already show declines in nesting success linked to beach loss and increased inundation.

9. Salmon populations retract from warm rivers.

Pacific salmon life cycles depend on cool, well-oxygenated rivers. With warming waters, some river segments become too hot or low in flow to support juvenile survival. As a result, salmon runs are withdrawing from their lower elevation reaches and surviving only in upstream, cooler headwaters.

These contractions fragment populations and reduce overall numbers. In some places, rivers once full of salmon no longer host runs. Upstream-only survival increases strain on habitat, food, and interspecies interactions.

10. Insect pollinators drop out in heated zones.

Bees, butterflies, and other pollinators often have narrow thermal limits tied to floral resources and microclimates. As heat intensifies, some populations collapse in their lower elevational or latitudinal zones. For example, studies warn that bumblebee nests overheat under rising temperatures, reducing brood survival.

When pollinators vanish locally, plant reproduction suffers, cascading into wider community decline. The shift also encourages range contraction toward cooler zones, but suitable habitat may be limited or fragmented, leaving species squeezed out of their former ranges.