Tunnels carved in stone may hide an ancient mystery.

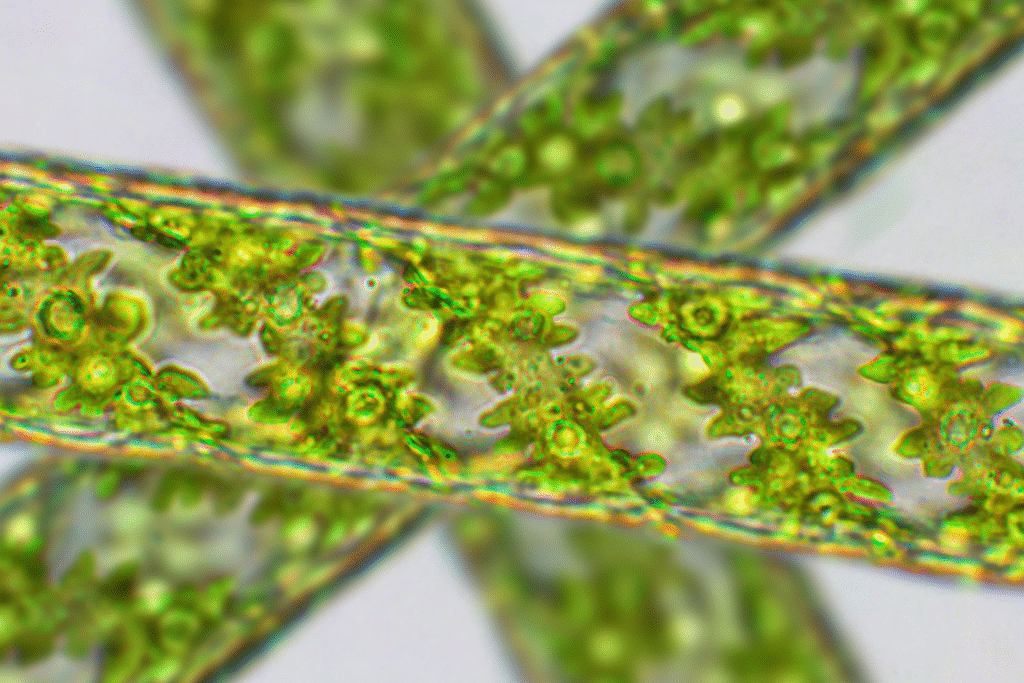

Researchers recently uncovered micro-scale tunnels inside marble and limestone in deserts across Namibia, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, structures so finely formed that they defy easy explanation. The tubes are typically about half a millimeter across and extend several centimeters, arranged in parallel bundles. Weathering and geological processes don’t fully explain their regular geometry and composition. Scientists propose a biological origin, perhaps a long lost microbe that bored through rock, though no direct fossil or DNA evidence has yet been found. The tunnels may point to unknown life-forms once active inside the planet’s solid crust.

1. Micro-burrows appear deep within rock surfaces.

In marble and limestone outcrops, scientists saw tiny tunnel systems etched into the rock interior, not just surface cracks. These micro-burrows run parallel in bands and often originate away from obvious fractures, as discovered by geologists working on the formations. Their consistent spacing and depth suggest intentional excavation rather than random decay.

Because they are beneath rock surfaces and not open to the atmosphere, these tunnels could only have formed from within. That interior origin removes many of the natural erosion or fracturing explanations and steers the idea toward biological agents.

2. They can stretch several centimeters in length.

These tunnels are more than brief punctures, they often span lengths of up to three centimeters or more in the rock, as stated by field reports following microscopic and imaging study. The lengths and continuity of these burrows challenge the notion that they were made by simple cracks or fluid flow.

Such dimensions require sustained activity. A life-based agent could plow through the mineral matrix slowly, leaving a slender trace. The length allows for growth, branching, or movement within the stone body.

3. The tunnels are too regular to be geologic.

The micro-burrows appear in parallel, uniform bands and resist explanation by common chemical dissolution or fracturing, as reported by scientists who analyzed their microstructure. The geometry is coherent and repeated, not chaotic or erratic as would be expected from natural cracking.

Such order hints at control, an internal sculpting process. When researchers examined the lining of the tunnels, they found mineral residues consistent with dissolution and reprecipitation, offering a footprint of what may have been biological boring.

4. Calcium carbonate dust fills many tunnels.

Inside the burrows, a fine dust of calcium carbonate has been found, suggesting that the tunnel makers may have dissolved or excreted minerals as they advanced. This residue appears compacted and continuous along the interiors, indicating active transport or chemical alteration by the agent.

If a life-form tunneled slowly through the rock, it would likely leave mineral debris behind, and these deposits hint at that mechanism. The dust’s consistency and placement strengthen the case for nonrandom origin.

5. No DNA or proteins were recoverable in samples.

Despite the clear structural evidence, analysts could not detect any preserved biomolecules—no DNA, proteins, or lipids, in the mineral infill. The tunnels seem to be ancient, perhaps a million to two million years old, likely too old to preserve organic signatures.

This lack of molecular traces leaves the biology hypothesis unproven. It forces scientists to rely on morphology, mineral chemistry, and spatial patterns rather than direct genetic evidence. The ghost of the organism remains invisible.

6. Unknown agent may have been an endolithic microbe.

The most plausible candidate is an endolithic microorganism, one that lives inside rock, perhaps a novel type with mineral-boring abilities. Known microbes like some cyanobacteria, fungi, or bacteria do etch into rock, but none match the regularity, depth, or extent of these tunnels.

If such a microbe existed, it likely used chemical leaching of mineral substrates as an energy source or nutrient route. Its ecology would have differed from surface life, perhaps adapted to dark, low-energy environments deep within stone.

7. The tunnels span deserts in multiple continents.

These formations are not limited to one location; geologists have documented them in rock across Namibia, Oman, and parts of Saudi Arabia. This wide distribution argues against a local oddity and suggests a broader ancient phenomenon, maybe tied to past climates or geological settings.

The fact that analogous tunnels emerge in separate deserts suggests that similar conditions enabled the same kind of tunneling. That parallelism strengthens the notion that a singular biological strategy once operated across distant regions.

8. Discovery shifts views on subsurface life.

These tunnels challenge assumptions about where life could ever exist. Instead of being constrained to surfaces or soil, there is evidence that life may once have chewed through solid rock. The find widens the range of ecological possibilities and raises the question of whether such organisms might still live hidden inside planetary interiors.

If a life-form carved these tunnels, it may alter interpretations of biosignatures on Earth and other planets. The search for life in seemingly inhospitable zones, rock, deep subsurface, even other planets—may now include tunnels like these as possible evidence of ancient or extant life.