The timeline of arrival may no longer hold.

For decades, textbooks pointed to a narrow window when the first people crossed into North America. The dates were debated, but the framework felt stable. Then, preserved in layers of sediment in what is now New Mexico, a sequence of human footprints surfaced with an age estimate that stretches that timeline far deeper into the past. If the dating holds, it suggests humans were present during a period many researchers believed was unlikely. The implications reach well beyond one site.

1. New dating confirms footprints are 21,000–23,000 years old.

Multiple dating methods now converge on that time window for the White Sands human trackways. The latest study used radiocarbon dating of ancient wetland muds and lake sediments, and found ages between 20,700 and 22,400 years, matching earlier seed and pollen dates. This third line of evidence strengthens the case that the footprints really are that old, pushing human presence in the Americas much earlier than once thought. (as reported by USGS)

That alignment across different materials and laboratories reduces the chances of dating error being just a fluke. It implies that footprints belong to a very deep, Ice Age chapter of human movement.

2. The footprints challenge the Clovis-first migration model.

Because the age of these prints significantly predates most Clovis artifacts, they undercut the long held idea that Clovis people were the first Americans. Clovis refers to a prehistoric culture identified by distinctive stone spear points found across North America and long considered the earliest clear evidence of human settlement on the continent. According to revised models, humans may have entered much earlier than that. The discrepancy invites reconsideration of migration routes and cultural continuity.

If these footprints indeed reflect early arrivals, then the later Clovis culture might represent a secondary wave or even a cultural reinvention rather than the first human occupation.

3. The location is White Sands’ paleolake shorelines.

The tracks come from the shores of ancient Lake Otero in the Tularosa Basin, where conditions favored preservation. Researchers found footprints in gypsum-rich soils and lake sediments located on what was once a marshy floodplain. These settings allowed high resolution imprinting and protection from erosion.

Such environments are rare in the archaeological record, which might explain why earlier arrivals have left so little evidence. The find underscores how geography and geology can invisibly filter out much of human presence across deep time.

4. Skepticism remains over carbon sources and context.

Some critics argue that dating seeds of aquatic plants like Ruppia cirrhosa may inflate ages because those plants absorb “old carbon” from water rather than atmospheric CO₂. That concern cast doubt on earlier dates and still motivates scrutiny of sediment context and contamination.

Because dating methods rely heavily on assumptions about carbon dynamics, even confident estimates invite debate. The newer mud dating helps, but not all remain convinced until more lines of evidence pile up.

5. The footprints show humans in Ice Age conditions.

These people walked during the Last Glacial Maximum, an era of cold climate, lowered sea levels, and shifting water courses. Their presence at White Sands suggests they survived, moved, and perhaps adapted in extreme environments. It implies technology, mobility, and resource use were more advanced than we often imagine for that time.

Understanding how they navigated glacial landscapes, accessed freshwater, hunted megafauna, and exchanged knowledge rewrites assumptions about early human ecological flexibility in the Americas.

6. No associated artifacts have been found nearby.

Despite the clear footprints, archaeologists have not found definite tools, campsites, or cultural debris directly linked to the trackmakers. The transient nature of footprints—people merely passing through—makes artifact recovery difficult.

Some suggest the trackmakers carried few material goods or that such materials decayed or eroded. Others propose that they traveled lightly or simply did not settle long enough to leave durable remains.

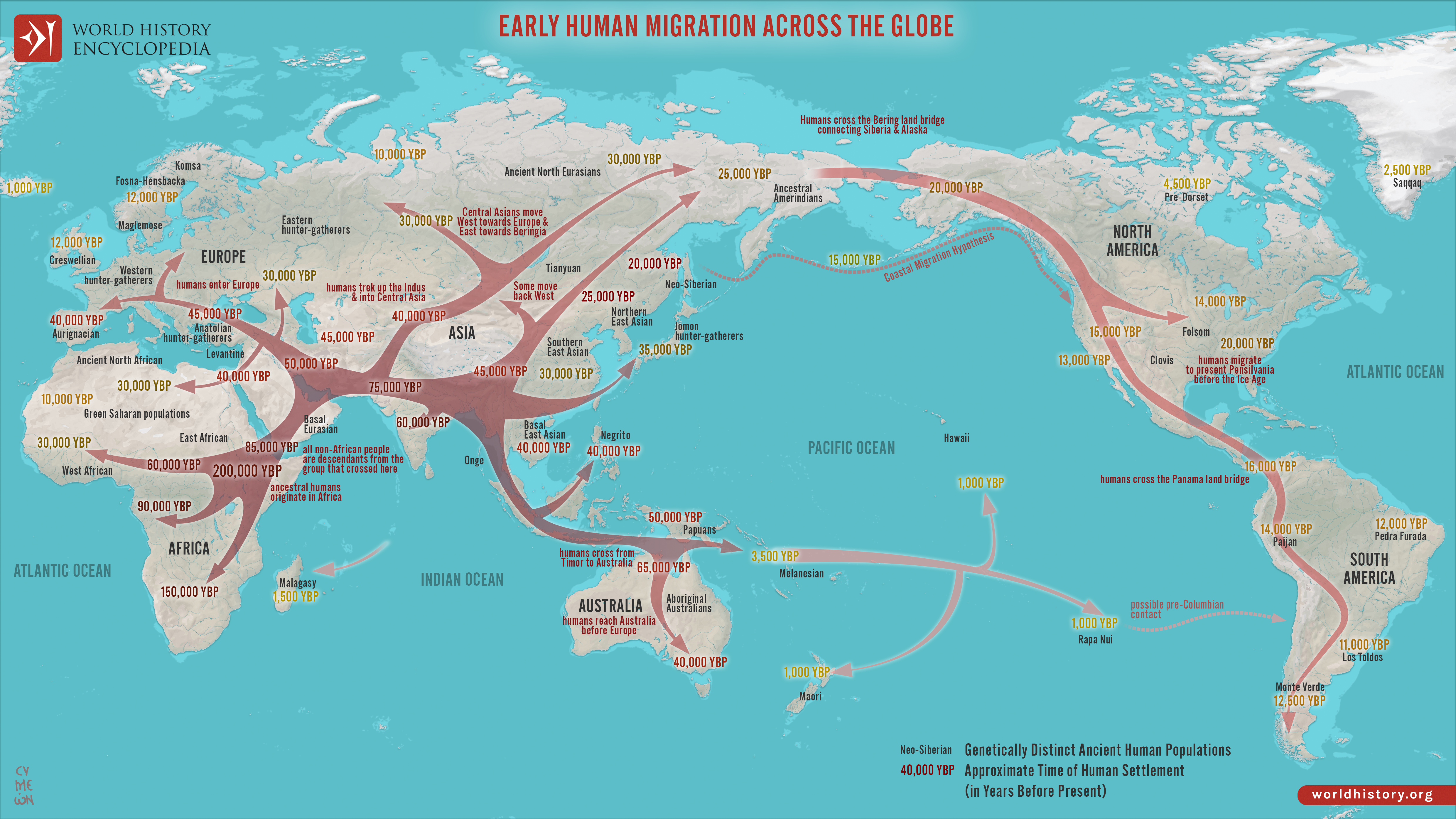

7. Migration routes now gain fresh reconsideration.

If people were in New Mexico so early, migration pathways may have included interior corridors or slow coastal hugging over long spans. The Bering Land Bridge, ice-free corridors, or Pacific coastal routes remain plausible, but the timing shifts open room for novel route models.

This date forces more complex models where multiple waves, back-and-forth movement, and long lags might explain how human populations structured themselves across the continent.

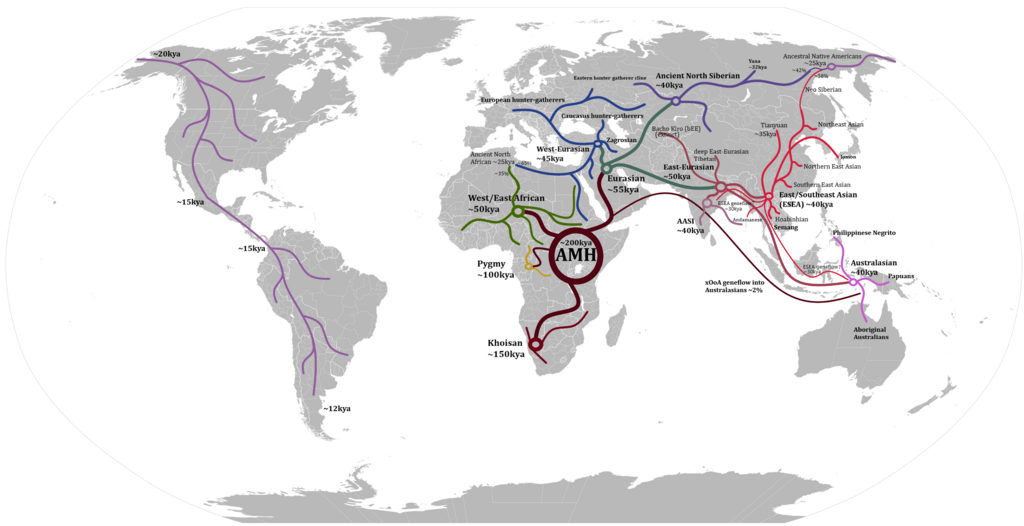

8. Genetic models may need revision.

Current genetic models that trace Native American ancestry back to Beringian founders may not fully capture earlier gene flow episodes. These early arrivals, if they exist, might represent lineages either fully absorbed or replaced, undetected by modern genome sampling.

Thus, population genomics may need to include “ghost lineages” or earlier admixture events to reconcile ancient footprints with present genetic patterns.

9. Climate and environment supported early habitation.

Paleoecological data suggest that Lake Otero and surrounding floodplains supported flora and fauna in wetter phases. Aquatic plants, water sources, and animal tracks indicate that humans could find food, water, and mobility corridors. Earth observations of ancient wetlands align with human footprint epochs.

Such wetlands may have acted as attractors, drawing people into otherwise marginal landscapes, and serving as ecological waypoints amid glacial environments.

10. This finding reframes human arrival as gradual and multilayered.

Instead of one sweeping migration wave, early human movement into the Americas may have been episodic, regionally diverse, and spread over millennia. The White Sands footprints suggest humans were present in the interior long before widespread stone tool traditions appear.

Scholars are now more open to mosaic models of entry and occupation, where multiple groups, routes, and timings shaped the peopling of the New World. The footprints are just one landmark in that unfolding story.