A mysterious healer’s chamber emerges.

A new archaeological discovery in Egypt has unearthed what appears to be the tomb of a healer from the Twenty-First Dynasty, complete with surgical tools preserved in situ. The find promises a fresh window into medical practice in a turbulent era of Egyptian history, when spiritual and empirical healing were deeply entangled.

In exploring this chamber, archaeologists report instruments that may have been used for incisions, bone work and internal probing. The tomb itself shows ritual and medical symbols intertwined, suggesting that the deceased was venerated not only as a healer but perhaps also as a ritual specialist bridging the worlds of life, death, and disease.

1. The tomb bears clear healer’s insignia.

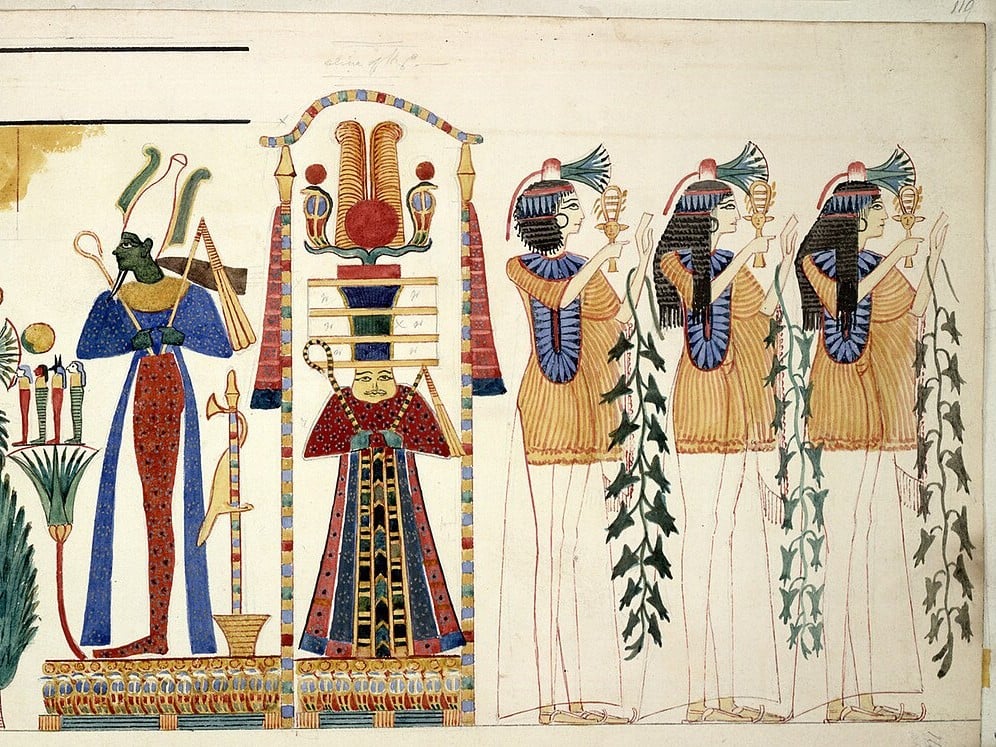

The entrance and interior walls carry iconography of snakes, lotus plants, and depictions of healing gestures, motifs long associated with medicine and renewal in ancient Egypt. These signs strongly suggest the occupant was recognized in life as a healer, not merely buried with tools as a symbolic set.

Inside the funerary chamber, plastered niches hold small jars, perhaps ointments, and reliefs show hands handling knives or probing tools. The visual program weaves medical and spiritual meanings, reminding us that in ancient Egypt the boundary between healing and magic was porous.

2. The surgical instruments remain remarkably intact.

Among the preserved artifacts are metal blades, probes shaped with delicate tips, and bone or ivory handles still in position on burial shelves. The corrosion is modest in many pieces, indicating careful burial conditions and minimal disturbance over time.

Some tools appear similar in form to those described in later medical papyri, perhaps rudimentary scalpels or cautery rods, although their precise uses remain speculative until further analysis. By placing them in a sealed burial context, we now have a near-pristine snapshot of what a practicing healer might have actually employed.

3. Radiocarbon dating places this in the late Third Intermediate Period.

Initial carbon dating of organic residues (linen wrapping, wooden handles) has yielded dates consistent with Dynasty 21 (around 1070–945 BCE). This helps anchor the tomb into the historical flux following the New Kingdom’s collapse and preceding the later Late Period. According to radiocarbon labs, the date ranges overlap with known transitions in priesthood and medical authority in Egypt.

This chronological anchoring is crucial because it situates the healer in an era when central power was diffuse and religious healing roles often merged with civic authority. That transition likely shaped how medicine was practiced and transmitted during the later centuries.

4. Trace residue analysis hints at herbal compounds.

Chemical analysis of residues in small jars beside tools indicates presence of plant compounds, possibly resins or waxes mixed with botanical extracts. These may have been antiseptics, binding agents or even analgesics used alongside tool work.

Such findings mirror what we know from medical texts: ancient Egyptians used mixtures of honey, resins, oils, and plant extracts when dressing wounds or dealing with infections. The combination of tools and these compounds in a single burial strengthens the case for practical surgical work, not purely symbolic deposition.

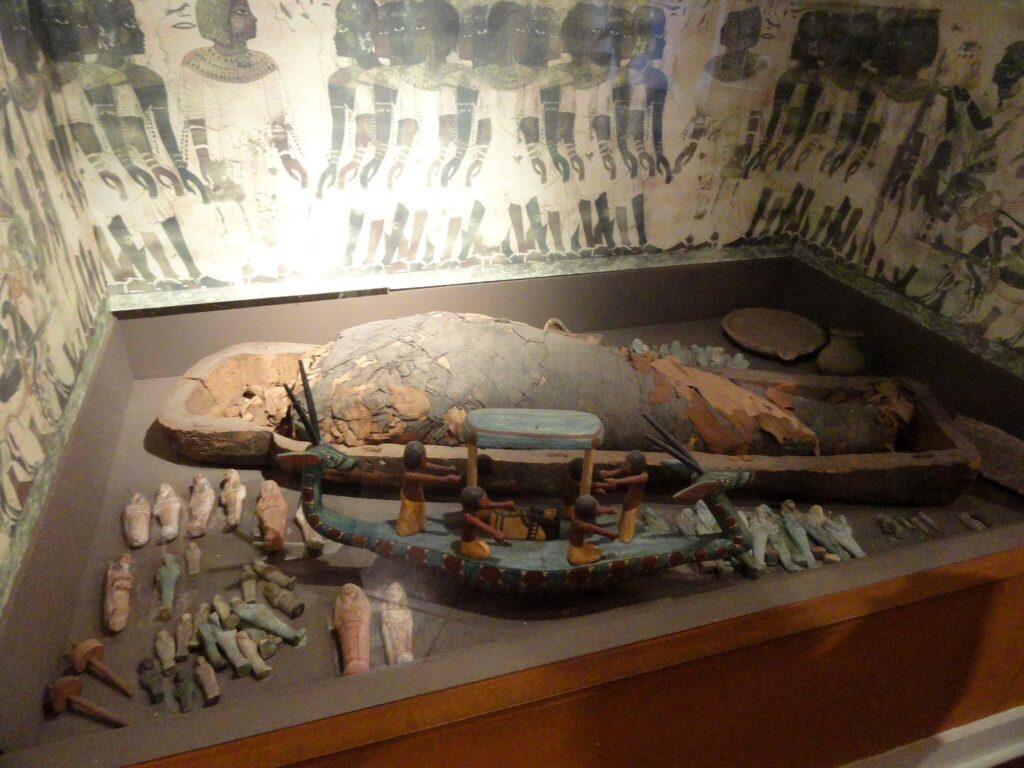

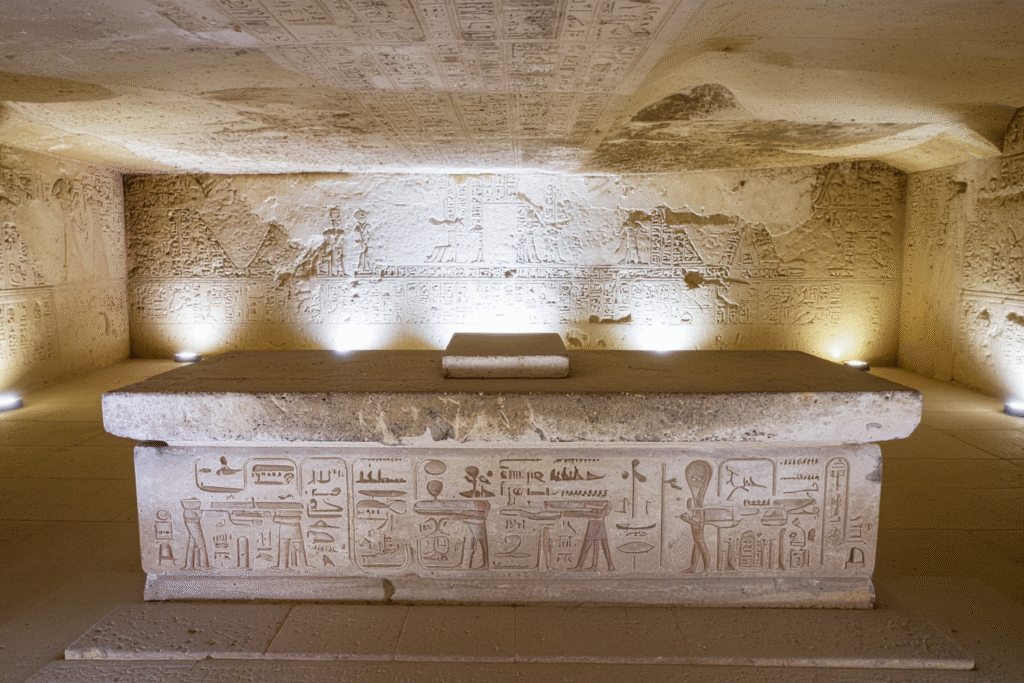

5. The tomb’s layout combines workshop and sanctuary space.

The interior plan shows a small side chamber with plastered walls and niches potentially for instrument racks or trays, adjacent to the burial niche. That suggests the tomb might also be conceived as a place of memorial ritual and perhaps continuation of healing rites after death.

In effect, the healer’s chamber seems designed as a hybrid: part tomb, part symbolic clinic. Visitors or priests could move through it, make offerings, and perhaps enact symbolic treatments — ensuring the healer’s powers persist in the netherworld.

6. This discovery reshapes our view of Egyptian medical practice.

Prior to this, many medical finds in Egypt were textual or fragmentary tools. To find a full surgical toolkit in context with a healer’s burial enables a more integrated view — one that bridges text, tool, ritual and social identity.

It suggests that healers held a more sacral status in certain periods, and that medicine was not solely a craft but a vocation combining science and faith. Future study may show how techniques moved across eras, influencing later Greco-Roman and Coptic medicine in Egypt.