Ancient artists met wild creatures in surprising ways.

Ever wondered what it was like the first time humans locked eyes with the wild animals they depended on—and feared most? Those moments are frozen in the pigments of ancient cave walls. The earliest paintings reveal more than just survival scenes; they expose a raw dialogue between humans and nature. Recent discoveries show that long before civilization, people were already storytellers, mapping their world through animals. Each stroke of ochre, each engraved line, tells us how our ancestors first made sense of the creatures that ruled their lives.

1. Humans painted animals long before they painted themselves.

In caves across Indonesia, France, and Spain, animals dominate the walls while human forms are rare or abstract. This imbalance hints that animals held deeper cultural weight, possibly symbolizing power or survival itself. Researchers studying Sulawesi’s cave art found that wild pigs were portrayed with striking realism as stated by Nature in 2021. These weren’t idle sketches; they were acts of reverence. When animals appear larger than people, it reminds us that early humans didn’t see themselves as rulers of nature but as one of its many inhabitants.

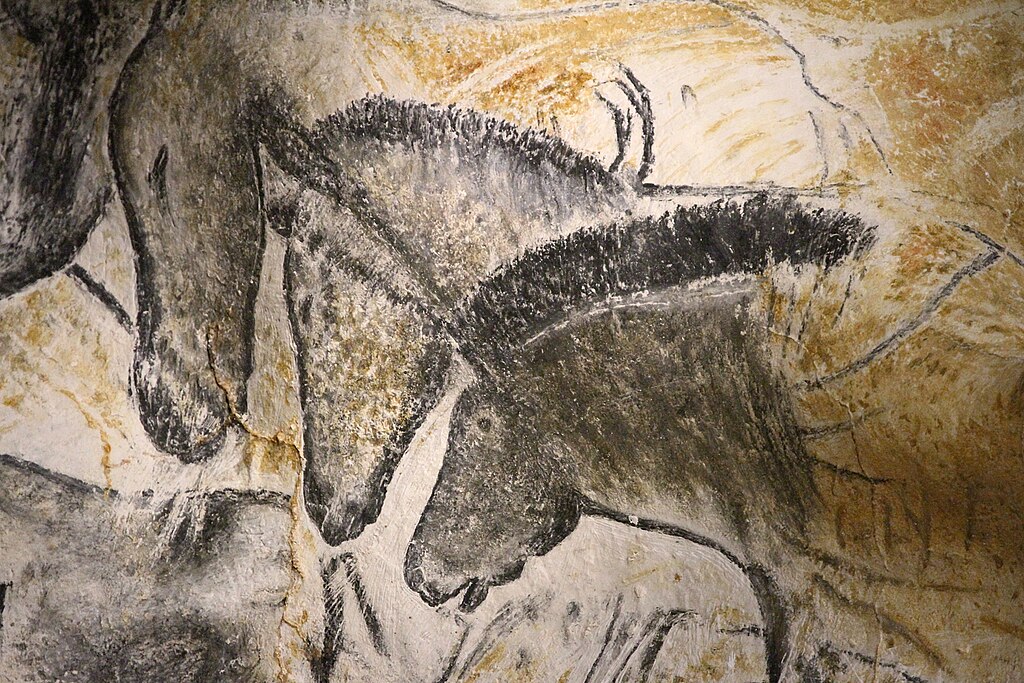

2. Some of the oldest animal paintings are over forty thousand years old.

Archaeologists date the oldest known figurative drawings of animals—massive wild bovids found in Borneo’s Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave—to around 40,000 years ago according to Science Advances. The pigments still cling to limestone walls where humans once sheltered from tropical rain. That timeline stretches back further than Europe’s famous Chauvet Cave, revealing that early storytelling through animal imagery wasn’t a local innovation but a shared human impulse. Across continents, art began where wildlife ruled, not where civilization bloomed.

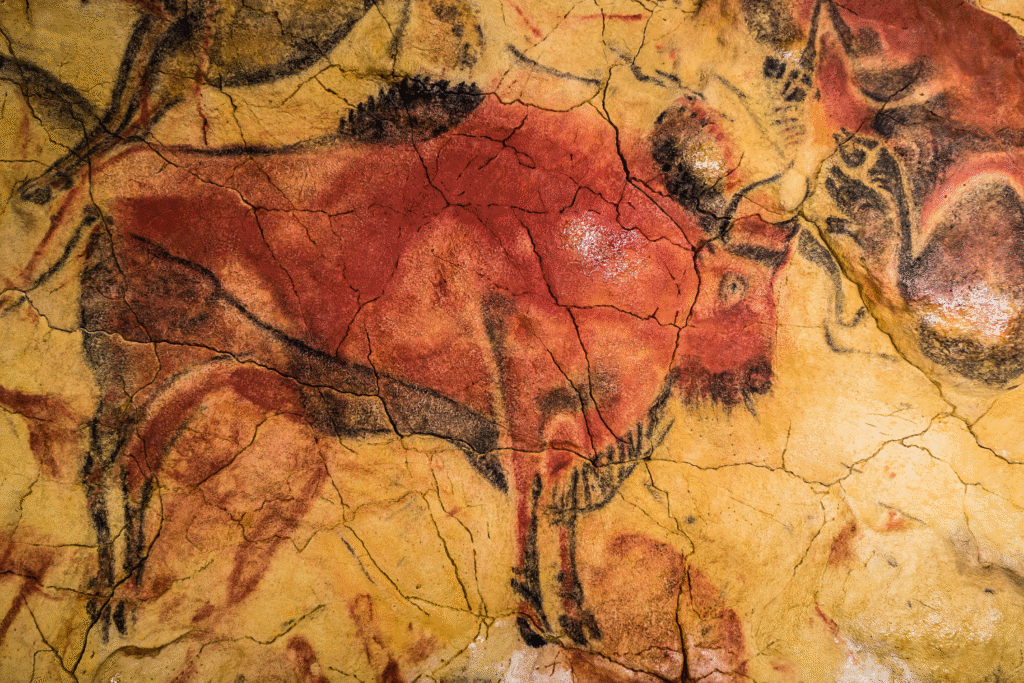

3. The precision of animal details shows deep observation.

At France’s Chauvet Cave, horses’ nostrils flare and lions crouch mid-pounce with uncanny accuracy, showing that the artists had watched them closely. They knew the roll of a bison’s shoulder, the twist of a mammoth’s trunk. This precision suggests familiarity beyond hunting, perhaps awe or ritual engagement, as discovered by the Journal of Archaeological Science. Such realism indicates that early painters studied animals as sentient counterparts. These depictions weren’t fantasy—they were field notes written in ochre and memory.

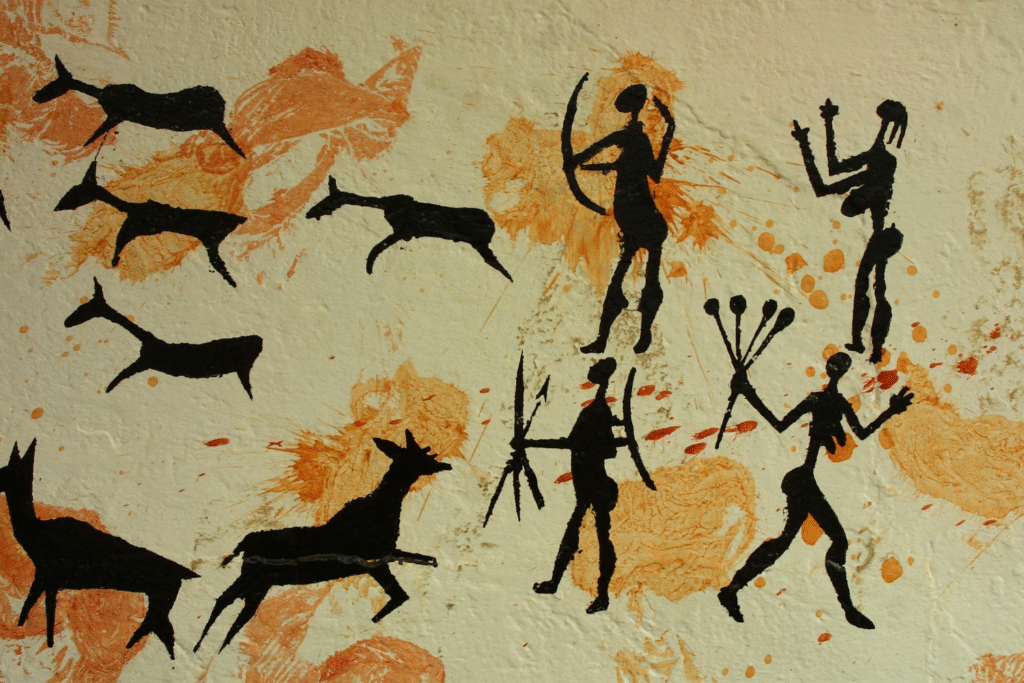

4. Many cave scenes depict humans in action with animals.

Some of the earliest visual storytelling shows people hunting, confronting, or dancing alongside animals. The scenes shift from still portraits to moving relationships, suggesting that humans saw themselves as part of the wild drama. In Spain’s El Castillo Cave, silhouettes of spearmen and charging deer merge into one rhythmic composition. These images likely marked community rituals or survival lessons, showing that art became a kind of shared history. They turn cave walls into living theaters of human-animal connection.

5. Animal choices varied with geography and cultural focus.

Caves in Europe teem with horses, mammoths, and bison, while Indonesian and Australian shelters show pigs, birds, and fish. Each region reveals a unique story about which species defined local life. Hunters immortalized what sustained or threatened them, and shamans may have painted what they feared or revered. That diversity suggests early humans weren’t just copying nature; they were curating their own ecological gallery. Each image served as both documentation and devotion to the creatures shaping their survival.

6. The placement of animal paintings suggests ritual purpose.

Many of these images are hidden deep within caves where daylight never reaches. To paint there, humans carried torches and mixed pigments in darkness, transforming walls into ceremonial spaces. The isolation adds weight to the idea that these paintings weren’t casual art but sacred acts. Animals may have represented spirits, ancestors, or forces of renewal. The choice to place them beyond ordinary reach implies reverence—and perhaps an early understanding that meaning often hides in shadow.

7. Some animals were painted behaving exactly as they moved.

Unlike static symbols, many creatures are shown in motion—galloping, grazing, or striking. This attention to behavior reveals an intimate grasp of animal life. Early humans didn’t just record what they saw; they captured essence and energy. The movement on those walls shows empathy and study, a bridge between observation and imagination. By freezing motion, they were preserving lessons about migration, danger, and rhythm—clues about how to survive among giants that once roamed freely around them.

8. Artists used natural rock contours to animate their subjects.

Cave painters often exploited bulges and curves in the rock so that animal bodies appeared lifelike by torchlight. A ridge might become a mammoth’s spine, a depression the shadow of an eye. This blending of art and geology shows remarkable creative intelligence. The cave itself became part of the artwork, transforming stone into skin. In a world without written language, those sculpted surfaces turned into silent storytellers that spoke through flickering light and ancient imagination.

9. The repetition of certain species hints at shared mythology.

Across distant continents, humans repeatedly painted similar animals—bison, horses, aurochs, and boars—suggesting shared mythic themes. Perhaps these species symbolized strength, fertility, or divine connection. The same animal appearing across thousands of miles points to a network of ideas older than nations. These repetitions show that animals weren’t merely observed but embedded in human mythmaking. By painting them again and again, people kept their stories alive and their worlds spiritually aligned with the creatures they depended on.

10. Cave art reflects the birth of human imagination itself.

When animals appeared on stone, humanity crossed a cognitive threshold—from reacting to nature to reflecting on it. Those first painters turned raw encounters into symbols, giving form to emotion and story. The walls of Chauvet, Sulawesi, and Altamira aren’t just remnants of prehistory; they’re mirrors of our shared consciousness. Every line carved or brushed was a declaration that humans could see, feel, and remember beyond instinct. Through animals, they learned to imagine—and through imagination, to be human.