The insects themselves matter less than what allowed them in.

The insects themselves matter less than what allowed them in.

For decades, Iceland stood apart as a rare exception, a place mosquitoes could not survive. That assumption has now cracked. Recent sightings suggest something fundamental has shifted, not suddenly, but enough to cross a line scientists long considered firm. The concern is not about itchy bites or summer nuisance. It is about temperature thresholds, breeding cycles, and what else might now be able to follow. Researchers are asking why this happened here, and why now, and what it signals next.

1. A backyard discovery in Reykjavik changed everything.

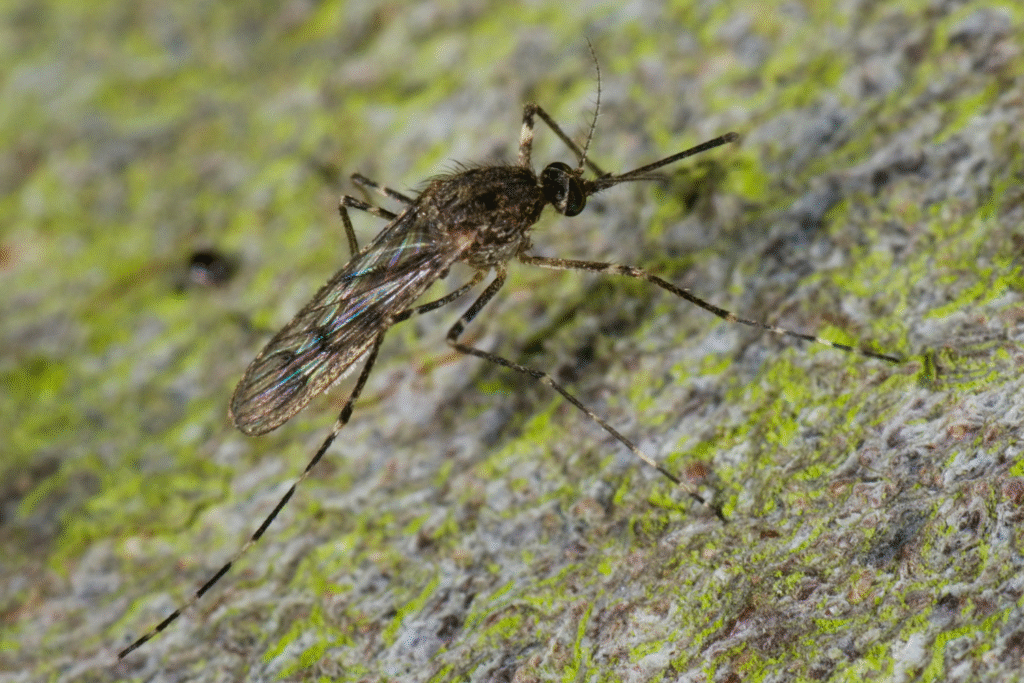

An amateur insect collector in Kjós thought he had trapped an odd type of fly until an entomologist at the Natural Science Institute identified it as Culiseta annulata, a species of mosquito known for surviving in cold climates. As reported by Euronews, the man had used a cloth soaked in red wine and sugar to attract moths but instead caught two female mosquitoes and one male. The discovery, small as it seemed, rippled across Iceland’s scientific community and drew immediate calls for ecological monitoring.

That moment redefined the country’s environmental narrative. A land that once prided itself on being mosquito-free suddenly had proof of their presence, alive and flying. Researchers began collecting climate data from surrounding areas, comparing recent temperature spikes with historical patterns. The results hinted that this may not be a one-time event. Iceland’s famously unpredictable weather, usually its best defense, now seemed to be turning in favor of insects evolution had built for resilience.

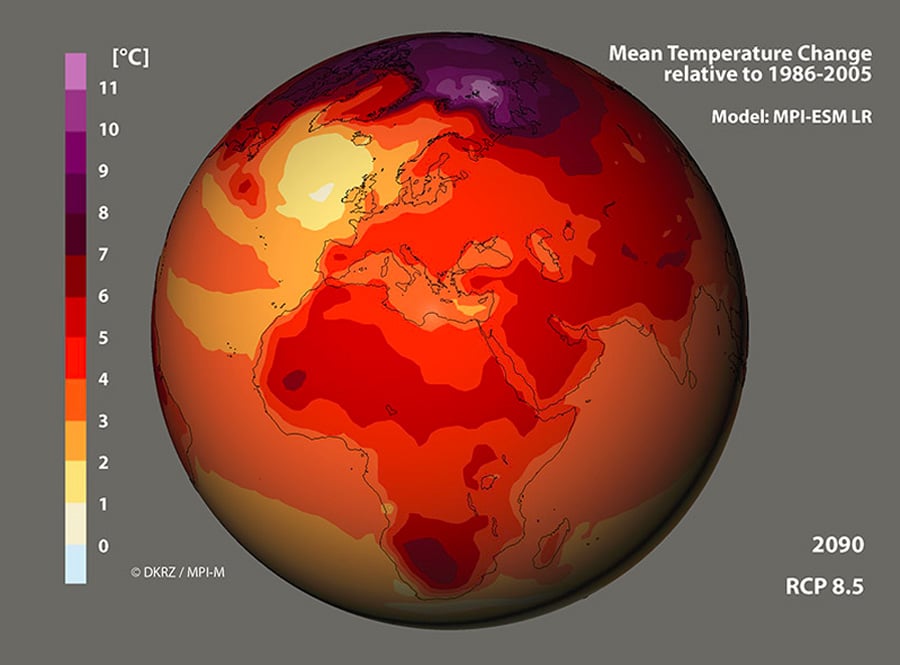

2. Climate patterns are warming faster than anyone expected.

Experts say the Arctic region, including Iceland, is warming up to four times faster than the rest of the northern hemisphere. That shift is creating mild winters and longer warm seasons, which are ideal conditions for mosquito survival. It means even a few days of unseasonably high temperatures could allow a small population to persist through the cold months, according to the BBC.

The speed of change is what unsettles scientists most. Iceland has recorded multiple record-breaking warm years over the last decade, with average winter lows rising noticeably. Frozen ponds now thaw earlier, snow arrives later, and precipitation comes as rain instead of snow. Those subtle changes, stacked together, create new chances for insects to thrive. A single season of survival could quickly turn into a permanent foothold if warming trends continue.

3. The species that appeared can tolerate brutal winters.

As stated by ABC News, Culiseta annulata is a hardy northern mosquito found across Europe and parts of Asia, well adapted to cold environments. Unlike tropical species that die off when frost hits, this one can overwinter as an adult in barns, attics, and caves, emerging again when temperatures rise. That unique adaptation gives it an enormous survival edge in climates that previously seemed impossible for mosquito life.

This species doesn’t rely on tropical humidity or constant heat. It can rest dormant for months, waiting for the right temperature cue to reactivate. Iceland’s increasingly mild spring thaws provide that cue. If enough adults make it through winter, they could begin breeding in sheltered microclimates like geothermal zones or animal barns — small pockets of warmth that now exist across the island’s landscape.

4. Scientists are racing to find out if they can breed.

Catching adult mosquitoes is one thing, finding larvae is another. The next step for Icelandic entomologists is to check standing water sources across the region for eggs and larvae, which would confirm active breeding. If that happens, it means the species has officially established itself in Iceland’s ecosystem.

For now, researchers are collecting samples from ponds and marshes to test that theory. They’re also using temperature models to simulate how long mosquito larvae could survive before freezing kills them off. Early indications suggest that the window for development has already lengthened by several weeks. It’s a small but significant sign that climate change is reshaping the life cycle of northern insects.

5. Iceland’s wetlands are now potential mosquito nurseries.

The island is covered in ponds, bogs, and small lakes, many of which were once too cold to support mosquito larvae. But shorter winters and earlier thaws are changing that. As temperatures rise, those calm, shallow waters stay liquid longer — just enough time for larvae to mature and emerge.

That environmental shift has biologists concerned. Iceland’s wetlands are rich with nutrients and organic debris, perfect breeding conditions if the climate remains mild. Even temporary breeding success could pave the way for mosquitoes to return each summer. And because wetlands also attract birds and livestock, these areas could become central to how the new insect population spreads.

6. Shipping routes might be helping them reach Iceland.

Scientists are still investigating how mosquitoes arrived at all. Some speculate that adults or larvae were accidentally transported through cargo, plants, or containers brought by ships and planes. Iceland’s busy trade links with Scandinavia and mainland Europe make such accidental stowaways plausible.

Others think natural expansion is also possible. With temperatures rising, northern European mosquito populations are pushing their range farther north each decade. Either way, human movement and climate change have blurred the lines of natural geography. Iceland, once buffered by the cold North Atlantic, is learning that isolation is no longer an effective barrier against ecological change.

7. Health officials say the immediate risk is minimal.

For now, health authorities are reassuring the public that Culiseta annulata does not transmit human diseases like dengue or malaria. Its bite may be irritating, but it’s not dangerous. Still, scientists emphasize the need for vigilance. As new species follow shifting climate corridors, Iceland could eventually host insects that carry pathogens previously confined to warmer latitudes.

That concern is why surveillance will ramp up next spring. Environmental agencies plan to set up monitoring traps around Reykjavik and northern coastal towns. The goal is to track timing, population density, and survival rates. Iceland’s “first mosquitoes” may not pose a health crisis, but they’ve introduced a new era of environmental responsibility.

8. Local communities are already noticing small changes outdoors.

Residents near Kjós have begun reporting faint evening swarms near barns and greenhouses — something unheard of just a few years ago. Farmers have seen insects hovering over water troughs or resting on livestock during milder evenings. The shift has sparked both curiosity and concern.

In a country famous for its absence of biting bugs, even a few sightings stand out. Some locals have started installing window screens and using repellents for the first time. The cultural adjustment is striking, revealing how quickly climate effects can touch everyday life in small, visible ways.

9. The event is a warning to other cold nations.

What’s happening in Iceland could foreshadow what’s next for other northern territories. Countries like Greenland, parts of Alaska, and northern Norway share similar climatic thresholds that once made mosquitoes nearly impossible. As temperatures rise, those barriers will erode too.

Researchers studying Arctic biodiversity say this isn’t just about mosquitoes. It’s a sign that entire ecosystems — from insects to plants to birds — are redrawing their borders. Iceland’s experience provides a glimpse of what happens when the planet’s coldest habitats begin to thaw and open to life forms that once couldn’t survive there.

10. Mosquitoes have become a quiet symbol of climate change.

The arrival of three small insects might sound trivial, but to scientists, it’s symbolic. These mosquitoes represent the creeping reach of climate change, the kind that doesn’t announce itself with hurricanes or fires, but with quiet adaptation. Iceland’s pristine isolation couldn’t stop it.

This shift reveals how fragile environmental boundaries truly are. If mosquitoes can reach Iceland, one of the world’s last safe zones, then every ecosystem is in play. The story began with one curious collector in a garden, but it may end as one of the clearest signs yet that the Arctic is changing faster than anyone imagined.