Ancient oceans held steady until our era.

In one of the most comprehensive studies of its kind, researchers have confirmed that global sea levels are climbing faster now than at any point in the last four millennia. By reconstructing sea-level patterns from coral cores, salt marshes, and sediment records, scientists found a sudden acceleration beginning in the late 19th century. For most of human civilization, sea levels barely shifted. That balance is now gone. The discovery reframes modern coastal flooding not as an isolated problem, but as evidence that the planet has entered an entirely new phase of ocean change.

1. Scientists confirmed a speed never seen in 4,000 years.

Using hundreds of geological samples across multiple continents, researchers found that global mean sea level has risen roughly 1.5 millimeters per year since 1900—a pace unmatched in at least four millennia, as discovered by scientists from Rutgers University and CSIRO. Prior to industrialization, sea levels fluctuated only within a few inches over centuries. That changed dramatically once fossil fuel combustion intensified.

This means the ocean’s quiet balance, which held steady through ancient civilizations and ice-age remnants, has now tipped irreversibly. The numbers aren’t abstract—they represent a planetary system now moving faster than it naturally can adjust.

2. The era of oceanic stability ended within one human lifetime.

Data compiled by global climate archives show that the stable conditions of the past 4,000 years collapsed in less than 150. The average annual rise jumped from 0.2 to 1.5 millimeters, according to NASA. That sevenfold acceleration coincides exactly with the surge of greenhouse gases from industry, transportation, and agriculture.

When seen in that light, sea-level rise becomes a modern phenomenon, not a slow geological one. The shift didn’t need thousands of years—it happened between grandparents and grandchildren. It’s a reminder that human activity can accelerate Earth systems far faster than nature’s normal pace, reshaping coastlines before societies even adapt.

3. Ocean warming and melting ice are driving the change.

As stated by Nature, the twin causes of today’s sea-level rise are thermal expansion from warming water and meltwater from ice sheets and glaciers. Each degree of ocean warming causes seawater to expand slightly, while shrinking ice in Greenland and Antarctica adds millions of tons of liquid to the sea each day.

These two forces combine into a feedback loop. The more the planet warms, the faster the ice melts, and the more the ocean swells. Scientists tracking these processes now call the current rate “unprecedented in the Holocene,” meaning it hasn’t happened since the dawn of human agriculture.

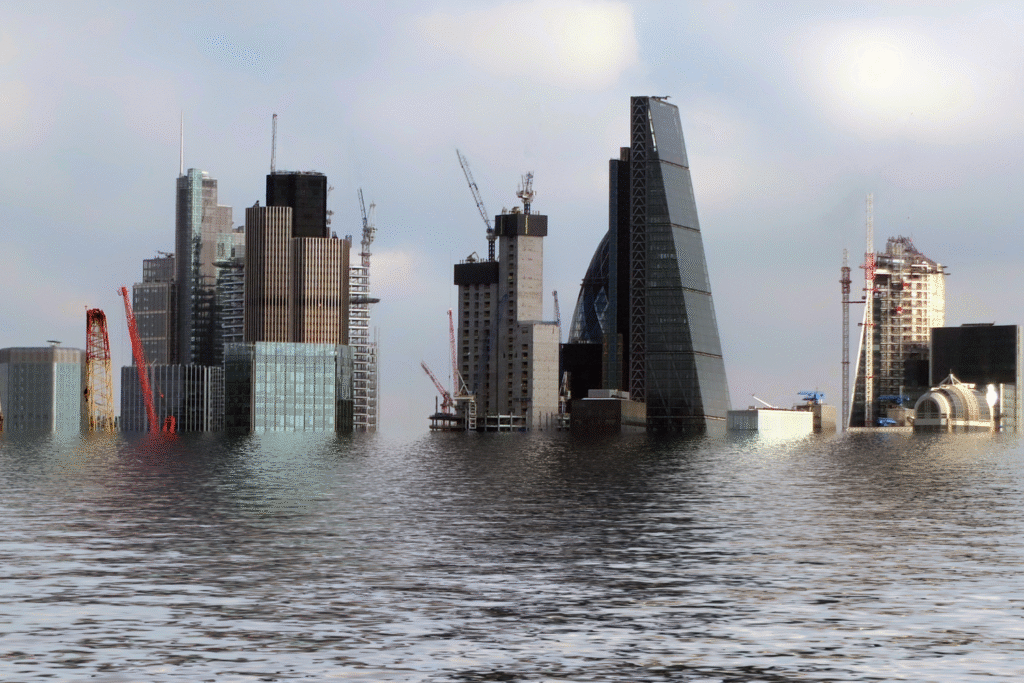

4. Rising tides are already reshaping coastal geography.

Beaches that once defined coastlines are now eroding faster than communities can respond. In places like Louisiana, Bangladesh, and Pacific atolls, shorelines retreat by several meters each year. Once-per-century floods now arrive every decade, and high-tide flooding is creeping into coastal streets. These changes reveal that the modern sea-level crisis is no longer theoretical—it’s visibly redrawing maps.

Each inch of rise may sound small, but its effect multiplies with storms and tides. Even moderate surges can overwhelm infrastructure designed for older baselines, making coastal living a daily negotiation between safety and inevitability.

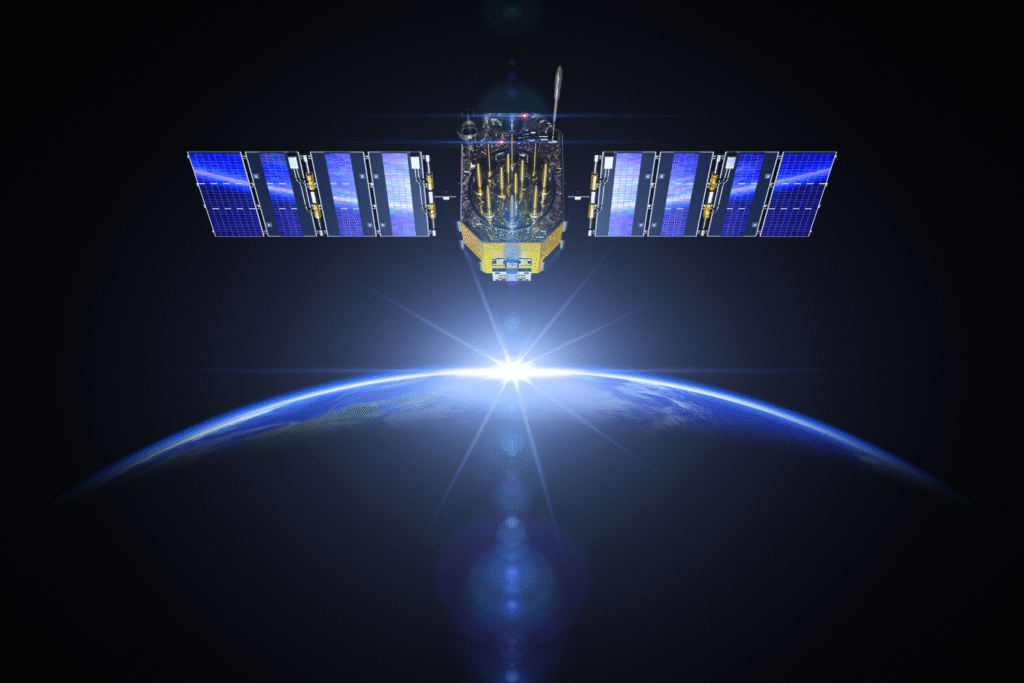

5. Satellite data confirms the rate is accelerating further.

Since NASA launched its first sea-level monitoring satellites in the early 1990s, the agency has recorded a rise of over 10 centimeters globally—an average of about 3.4 millimeters per year today. That rate is more than double what it was in the early 20th century. Every new decade adds precision to this alarming upward curve.

The acceleration means that the ocean’s surface isn’t just higher—it’s climbing faster each year. Scientists call this a “compounding rate of change,” where the speed itself becomes a risk factor. What feels incremental becomes exponential in just a few generations.

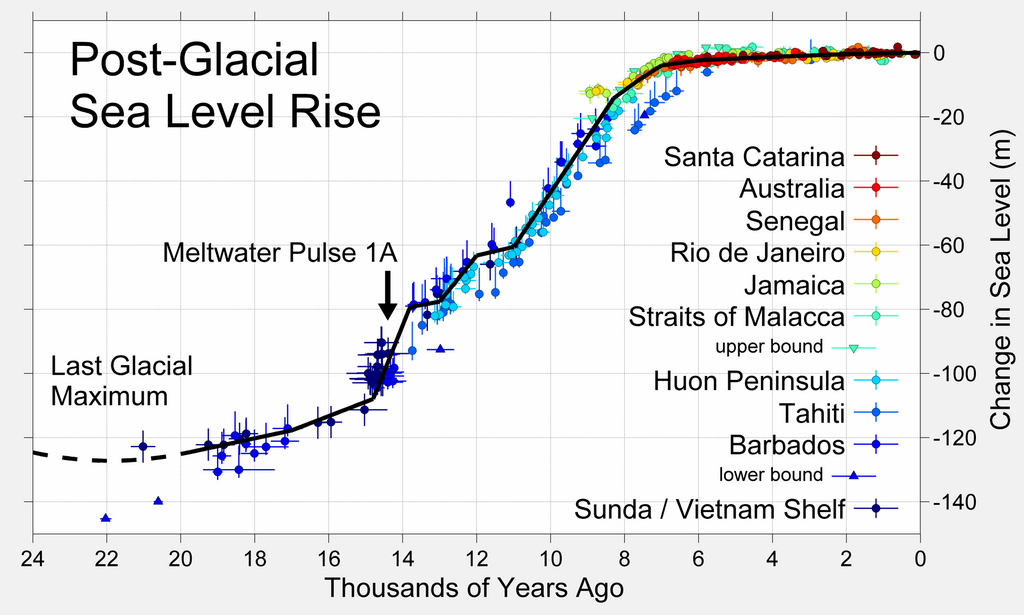

6. Ancient shorelines help scientists reconstruct past stability.

By studying fossilized coral reefs, salt marshes, and ancient mangrove deposits, researchers can see that for thousands of years after the last Ice Age, the sea found a balance. These natural markers show only gentle fluctuations—nothing like today’s rapid climb. They serve as a geological baseline for what “normal” once looked like.

Those quiet patterns of stability now act as contrast to modern data. Where ancient seas moved at a glacial pace, today’s rise looks more like a sharp upward spike. It’s a record written in coral and stone that shows how extraordinary our current era truly is.

7. Low-lying nations are being pushed to the brink.

Islands such as Tuvalu, Kiribati, and the Maldives have become poster children for sea-level rise, where freshwater contamination and erosion now threaten basic habitability. These countries contribute the least to global emissions yet face the most direct existential risks. For some, relocation of entire populations is becoming the only long-term option.

Beyond small islands, major cities like Jakarta, Miami, and Bangkok are also sinking faster due to both rising seas and local subsidence. This creates a dual crisis: the land drops as the ocean climbs, closing the margin of safety faster than adaptation plans can catch up.

8. The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are tipping points.

Scientists warn that the largest uncertainties for future sea-level rise lie within the polar ice sheets. If certain melting thresholds are crossed, massive sections of these glaciers could slide into the ocean irreversibly. That would add several meters to global sea levels over centuries—a change that no coastal defense could manage.

Researchers studying satellite data and ice cores say some parts of West Antarctica may already be past a “point of no return.” That phrase isn’t alarmism—it describes a feedback where melting creates more exposed ice, which melts even faster. The world is now racing against physics.

9. The human cost will define this century’s migrations.

As seas rise, millions may be displaced from coastal homes, triggering migrations that reshape demographics and economies. Entire cultural identities tied to coastal regions—from Louisiana bayou communities to Pacific islanders—face erasure. The economic burden, meanwhile, will be measured not in billions but in trillions as infrastructure must be rebuilt or abandoned.

The challenge stretches beyond engineering; it’s social and ethical. Deciding which regions to defend and which to yield may become one of the most difficult political choices of the 21st century, with climate justice hovering at the heart of every decision.

10. Scientists say there’s still time to slow the surge.

While the current pace of sea-level rise is unprecedented, it is not yet unstoppable. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions could slow ice loss and stabilize ocean expansion over time. The window is narrow but open. Scientists argue that every fraction of a degree of avoided warming translates directly into less ocean rise, less erosion, and fewer displaced people.

It’s not a simple fix, but the data point toward hope as much as warning. What we do now will decide if the next 4,000 years tell a story of continued acceleration—or one where humanity finally learned to steady the seas again.