A startling find surfaces inside ancient banquet architecture.

In the heart of Pompeii a newly uncovered banquet hall has revealed frescoes that plunge us into the secret world of the cult of Dionysus. The decorations stretch across three walls of a large dining space and depict hunting scenes, wine libations and initiation rites dating to roughly 40–30 BCE. With such vivid imagery, this discovery adds a dramatic new chapter to what we know about Roman ritual life beneath the ash of Mount Vesuvius.

1. Archaeologists uncovered the hall in Insula 10 of Regio IX.

During systematic excavation in the block known as Insula 10 of Regio IX at Pompeii, a large banquet room emerged, as reported by officials. According to the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, the room houses nearly life-size frescoes depicting a Dionysian procession. These scenes wrap three walls and open onto a garden, showing the space was designed for ceremonial dining and display.

Once the room was cleared, its scale became apparent. Not a simple triclinium but a grand hall, its size and decoration reflect a gathering place for guests where myth and ritual converged. The setting hints at how deeply culture and banquet life intertwined in Roman elite homes.

2. The frescoes date to about 40–30 BCE and combine ritual and artistry.

A large scale frieze spanning three sides of the room has been dated to the 1st century BCE, as stated by multiple sources at the site. The artwork belongs to the Second Style of Pompeian painting, and at the time of the eruption the frieze was already nearly a century old. It shows female followers of Dionysus, satyrs and animal sacrifices moving in a dramatic cycle of mythic enactment.

The dual nature of the imagery—hunter and worshipper, reveler and sacrificer—tells a story of transformation embedded in the space. In this hall the banquet becomes ritual, the guest becomes initiate, and the dining event takes on symbolism far beyond food and drink.

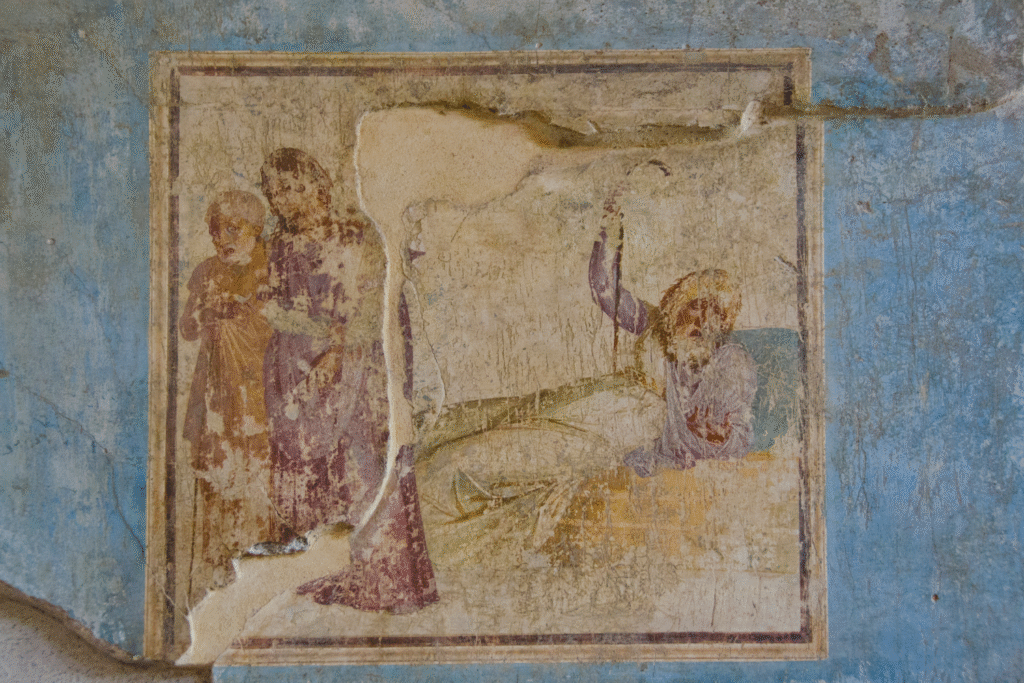

3. Figures in the frieze merge banquet decoration with mystery cult themes.

The scenes depict bacchantes holding slaughtered goats, young satyrs playing double flutes and an initiate about to enter the mysteries of Dionysus, as discovered by researchers. The central figure is flanked by Silenus holding a torch, signaling ritual entry. These details link the feast environment to religious experience.

The hall’s décor transformed what might have been a purely social event into something charged with spiritual significance. Guests sat among images recalling death, rebirth and ecstatic celebration; the frescoes invited reflection on the nature of transformation even as wine cups were passed.

4. The space opens to a garden, suggesting banqueting and ritual convergence.

One side of the hall opens onto a garden rather than another wall, creating a seamless transition between interior and exterior. This architectural choice enriches the experience of the banquet, letting guests move from the painted myth to real nature. As wine and ritual merged, the setting reinforced the sense of a journey from the everyday into the extraordinary.

That design reinforces how the hall was more than a dining room. It became a stage for enactment of mythic themes and embodied movement between domestic life and sacred narrative. Here, the garden welcomes movement outward while the fresco invites inward reflection.

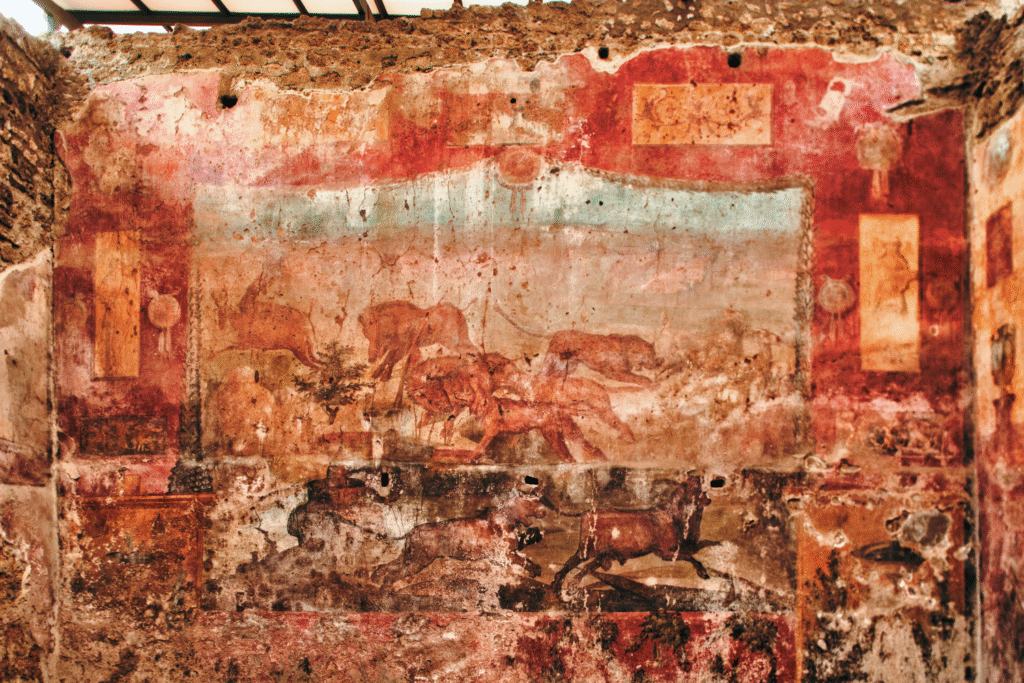

5. Hunting motifs in the mural evoke death, rebirth and wild vitality.

Above the banquet frieze a secondary band depicts living and dead animals—fawns, a freshly gutted boar, birds and shellfish—underscoring the ritual’s themes of life and sacrifice. Hunting imagery, unexpected in domestic decoration, signals the ancient belief that transformation often required release from the familiar.

Guests dining in that hall stood among scenes that asked more of them than taste and conversation. They were immersed in representations of primal struggle, of captivity and liberation, of moving from destruction into renewal via wine, dance and myth.

6. The discovery reshapes understanding of everyday space in Pompeii.

Until now many luxurious rooms in Pompeii were seen simply as performance spaces for elite display. But this hall shows how domestic architecture integrated myth, initiation and banquet in one place. The combination of elite dining and cultic imagery invites us to reconsider what lavish homes really meant in ancient Rome.

The find shifts the frame: banquets were not only about entertainment but about identity, transformation and social positioning. The guests in this room may have dined, yes—but they also became participants in an echo of ritual coded in paint and stone.

7. The frescoes share stylistic ties with the famous Villa of the Mysteries.

The new frieze in Pompeii evokes the famed frescoes of the Villa of the Mysteries—found about a century ago—yet adds hunting motifs and vivid life-size figures that refresh our view of second century BCE art. As reported by archaeological outlets, the room’s figures stand on pedestals like statues even as they appear caught in movement.

That comparison reminds us the Roman home was a canvas for myth. The new banquet hall joins a lineage of spaces where painting, architecture and ritual merged. And its similarities to the Villa encourage fresh questions about how widespread such décor might have been.

8. Preservation under Vesuvius ash kept detail and color intact.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, though catastrophic, preserved rooms such as this one under a thick layer of ash—shielding color, contours and meaning. The depth of the covering insulated frescoes from centuries of weather, offering modern viewers a window into ancient spectacle. What we see today echoes the hall’s brilliance just before doom struck.

Its survival reminds us that the everyday and the extraordinary once co-existed. A space meant for feast and myth lay buried and untouched until now, offering a direct link across millennia to banquet, ritual and memory in full color.

9. Public access is planned soon, integrating archaeology and tourism.

Excavators note that the hall will be opened to public tours in controlled numbers, supporting both preservation and public engagement. Site officials emphasize guided entries in small groups to maintain the fragile environment while sharing this extraordinary space. The balance of access and conservation is delicate yet essential.

When visitors step inside they will not only observe ancient myth but inhabit a room where wine, ritual and art once converged. This dimension transforms the visit into something more immersive than typical archaeological viewing.

10. The banquet hall invites fresh questions about Roman ritual life.

Beyond artistry and architecture the discovery prompts broader inquiry into how Romans understood feasting, identities and religion. The hall’s combination of mythic imagery, social gathering and ritual hints at networks of meaning deeper than entertainment alone. We now see a banquet that meant more than food.

The hall urges us to ask: who dined here, what did they feel, why did they decorate their walls with such potent imagery, and how did guests internalize the narratives laid before them? In that room the feast became metaphor, the guest became initiate, and the wall became scripture.