Scientific confirmation finally meets a family’s long memory.

More than one hundred years after Sitting Bull’s killing at Standing Rock, a fragile lock of his hair became the unlikely thread that stitched his story back to his descendants. DNA technology rose to meet what oral history protected, linking the nineteenth century Lakota world to Ernie LaPointe and his sisters. The past did not loosen its hold, it simply waited for science to catch up. The discovery reshaped how his story travels through time.

1. The young warrior grew into a strategist during turbulent expansion.

Born along the Yellowstone River in the 1830s, Sitting Bull entered a world already strained by American incursions into Lakota territory. His early years revolved around bison hunts, protective family circles, and the evolving diplomacy that held Plains alliances together. These foundations shaped the leader he later became according to Smithsonian Magazine.

He drew from this childhood reservoir for the rest of his life. His grounding in community responsibility remained central to Lakota decisions during every crisis.

2. Leadership sharpened as shifting treaties threatened Lakota lands.

By the 1850s and 1860s, territorial maps changed faster than any treaty could hold. Sitting Bull emerged as a voice unwilling to cede hunting grounds or accept unsafe resettlement. His stance hardened when federal agents pressured bands into agreements they never requested, a sequence documented as stated by the National Park Service.

His steady refusal resonated among families watching the Plains contract. The pressure built slowly, then abruptly, until resistance became the only viable path.

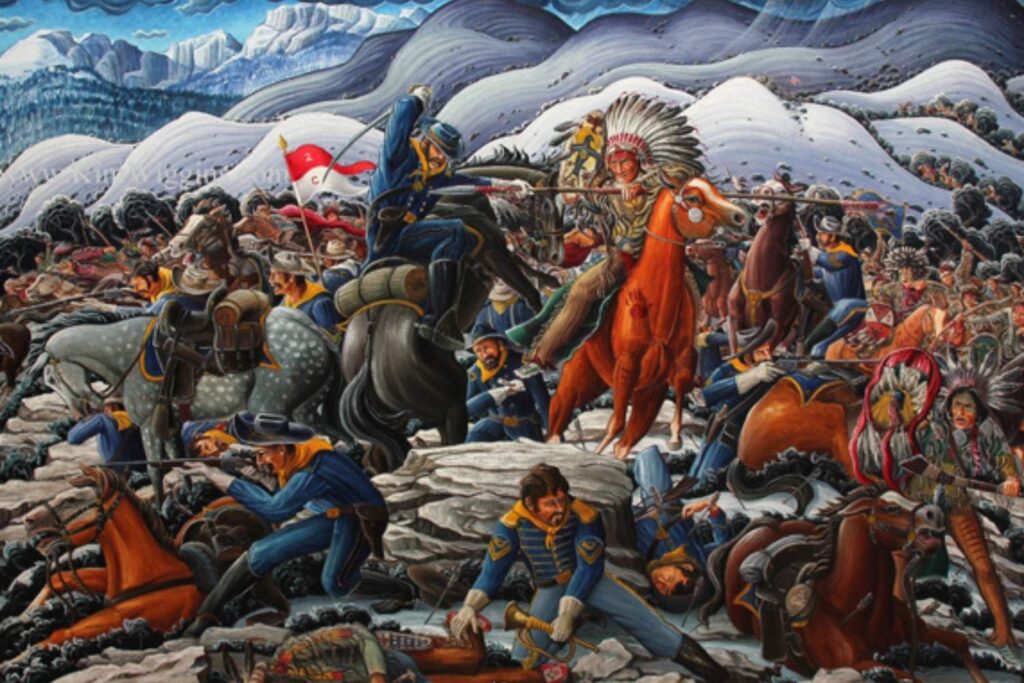

3. The fight for sovereignty intensified while alliances extended northward.

During the 1870s, conflict moved from negotiations to armed confrontation. The Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho unified around the urgent need to protect the last strongholds of the northern Plains. Their coordinated decisions and loyalties have been traced through archival testimonies as reported by PBS.

Survival required clarity, and Sitting Bull supplied it. His leadership steadied families navigating hunger, broken treaties, and the widening reach of U.S. military campaigns.

4. A decisive spiritual moment reframed the coming battle entirely.

In the spring of 1876, a ceremonial gathering brought a vision that predicted soldiers falling as if pulled from the sky. The interpretation circulated quickly, strengthening the resolve of allied camps preparing for conflict near the Little Bighorn River. The moment became almost inseparable from the historic battle that followed.

Communities carried both fear and purpose into the summer. His role was not to command troops but to hold unity, something few leaders could manage.

5. The aftermath of victory carried its own irreversible cost.

The defeat of Custer’s forces made headlines across the nation, but for Lakota families it made retaliation certain. The military response intensified, pushing communities toward exhaustion and eventual exile. Ultimately, Sitting Bull guided hundreds north into Canada where food was scarce and winters were unforgiving.

Returning to the United States under military control became unavoidable. The reservation era confronted him with political traps more dangerous than any battlefield.

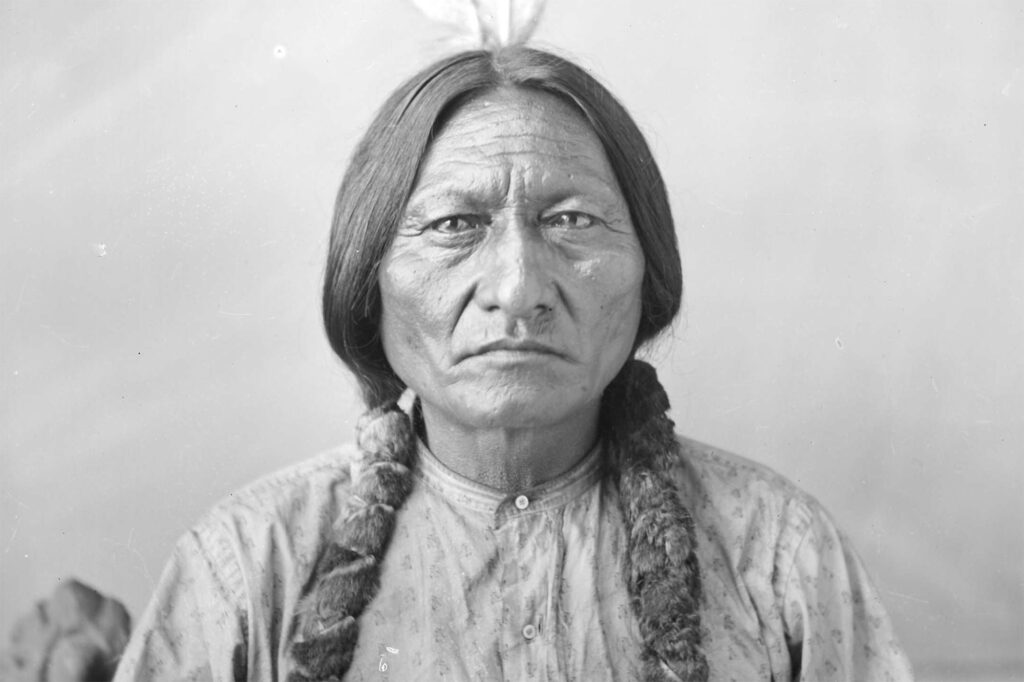

6. A fragile lock of hair survived where records did not.

After his death in December 1890, a small sample of his hair was taken and stored in museum collections far from Standing Rock. The strand moved from catalog drawers to climate controlled vaults as institutions reorganized collections through the twentieth century. It outlasted wars, relocations, and shifting curatorial practices.

Only recently did the hair become a biological archive. Its degraded fragments held genetic signatures no document could match.

7. The family guarding his memory waited longer than most histories recall.

Ernie LaPointe and his three sisters grew up knowing their lineage through stories protected within their household. Yet public institutions rarely recognized those connections. They spent decades repeating their history to scholars who often wanted paperwork rather than lived knowledge.

Patience became part of survival. They carried cultural responsibility without formal acknowledgment, waiting for a moment when scientific tools could match their memory.

8. Advanced genetic sequencing finally made the impossible achievable.

Researchers working with severely damaged samples used methods typically reserved for ancient remains. They isolated tiny sections of autosomal DNA from the preserved hair, recreating genomic markers compatible with living relatives. The work required precision and a near surgical approach to contamination control.

Once patterns emerged, the connection became statistically sound. The past, long out of reach, settled into measurable fact.

9. Scientific confirmation gave the family the recognition institutions denied.

When the DNA match aligned with Ernie LaPointe and his sisters, history shifted. The validation extended beyond personal identity, reshaping how museums, historians, and agencies referenced Sitting Bull’s line. The decision strengthened their role in cultural stewardship and repatriation discussions.

For the family, it felt less like discovery and more like justice. Their ancestors kept the lineage intact through memory alone until science finally named it aloud.

10. The link between past and present now belongs to them again.

The DNA confirmation restored authority to the people who lived closest to his legacy. It replaced doubt with clarity, giving future generations a direct line back to their ancestor’s world. The match also reframed Sitting Bull not as a distant figure of textbooks but as a relative whose descendants still speak for him.

That connection allows Lakota memory and modern science to coexist. The story now continues in the voices of his family, not the footnotes of outsiders.