Innovations shaped by landscapes few humans survive.

Archaeologists and engineers have started comparing Inuit technologies to modern cold-weather systems, and the results are surprising even to specialists. What began as a study of survival strategies has shifted into a deeper look at how a people living in some of the harshest climates on Earth built tools, shelters and transportation systems that rival today’s performance. The new findings show a pattern. Inuit technology was not improvised. It was engineered, refined and tested across centuries of ice, wind and darkness.\

1. Igloo construction reveals unmatched thermal engineering.

Recent thermal imaging studies found that igloos trap heat so efficiently that interior temperatures stabilize far above outside conditions according to Smithsonian Magazine. The dome shape redirects wind, while compacted snow acts as both insulation and structure. Researchers say the precision of block placement allows minimal heat loss in extreme Arctic storms. The design performs closer to modern passive heating models than to simple shelters.

Inside, air stratifies naturally, creating warm and cool zones without mechanical circulation. This gradient makes cooking, sleeping and tool work possible even when temperatures outside drop to conditions capable of freezing exposed skin in minutes.

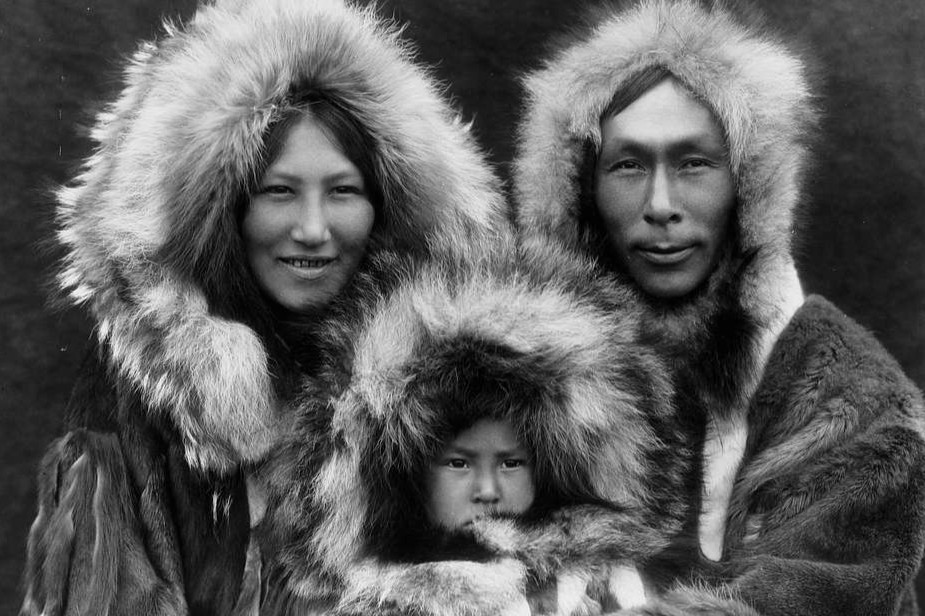

2. Inuit clothing systems outperform synthetic gear in testing.

Field experiments in northern Canada showed that caribou skin parkas outperform many modern insulated jackets as stated by National Geographic. The hollow hairs create thousands of air pockets that trap heat while allowing moisture to escape. This dual performance reduces sweat buildup, which is critical in environments where damp clothing becomes dangerous. The garments also layer in a way that distributes warmth evenly across moving joints.

Researchers studying mobility noticed something else. The clothing allows a full range of motion without compromising heat retention. The synergy between insulation and movement makes traditional outfits ideal for travel across shifting ice.

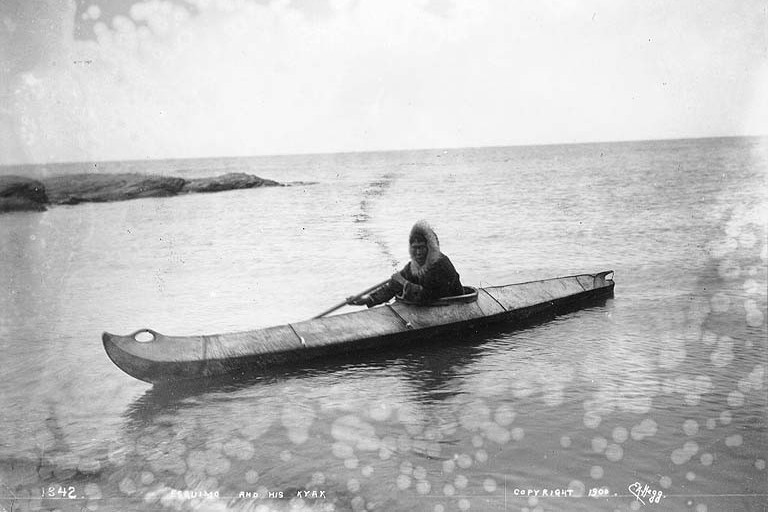

3. Kayak architecture mirrors hydrodynamic principles used today.

Marine engineers examining traditional Inuit kayaks found they follow the same stability and drag-reduction patterns seen in modern competitive vessels as reported by Scientific American. The narrow frame, stretched animal skin and precise weight distribution make the kayak extremely responsive in water. These boats cut through waves with minimal resistance, even in turbulent Arctic seas. Their lightweight design also allows for easy portaging over ice.

What impressed researchers most was the structural balance. The frame flexes slightly under pressure, absorbing shock from rough water. This adaptability gives kayaks exceptional durability without sacrificing speed or control.

4. Sled runners show sophisticated friction management.

Inuit sleds glide across hard snow using runners treated with fine layers of ice, soot or mud that reduce drag. This technique mimics lubrication models seen in modern cold-weather engineering. The treated surface lowers friction dramatically, giving sled teams the ability to travel long distances with minimal energy output. The method reflects generations of testing in shifting snow textures.

The materials also adjust easily to temperature changes. Runners can be resurfaced in minutes, allowing sleds to maintain performance even as conditions shift from powder to ice crust.

5. Hunting tools were streamlined for aerodynamic precision.

Harpoons, throwing boards and spears were shaped with weight distribution that improves accuracy and penetration. The leverage created by the throwing board increases speed while conserving energy. Hunters could strike moving targets over open water or across drifting ice with remarkable reliability. Archaeologists found consistencies in tool shape across distant regions, indicating shared engineering knowledge.

These tools reveal an understanding of lift and trajectory that predates aerodynamic modeling. Their balance reflects a deep awareness of how motion behaves in freezing air and how muscle power transfers through lightweight materials.

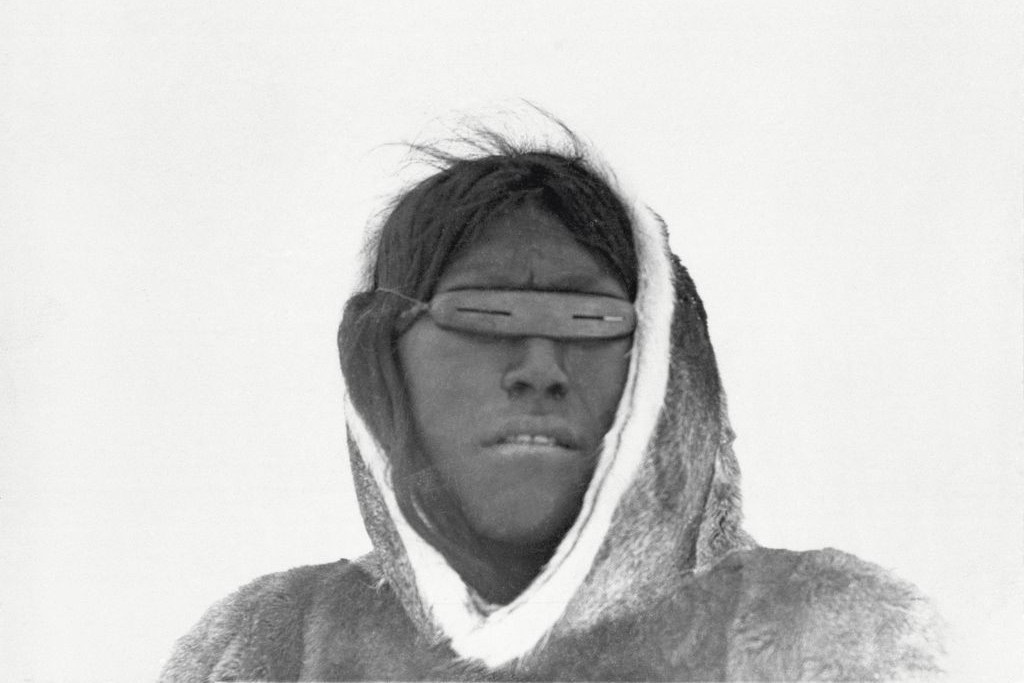

6. Snow goggles protected vision through optical science.

Slit-style snow goggles prevented blindness caused by intense glare reflected off ice. The narrow openings reduced light but enhanced contrast, making subtle contours visible during travel. The design acts like a primitive camera aperture, increasing depth perception in bright conditions. This allowed hunters and navigators to move confidently in landscapes where glare could disorient even seasoned Arctic travelers.

The goggles also reduce eye strain over long distances. By filtering excess light naturally, they preserve clarity without relying on tinted materials that can distort landmarks.

7. Stone lamps produced steady, efficient heat.

The qulliq, a carved stone lamp fueled by animal fat, served as a stable heat and light source. Its curved basin and wick placement optimize flame shape, producing clean, steady warmth with minimal smoke. The lamp’s output is surprisingly efficient for a non-pressurized system. Families used it for cooking, drying clothing and warming shelters through long polar nights.

Its reliability mattered most during storms. Even in poor oxygen conditions, the qulliq burned consistently, providing warmth when other fuel sources would fail or extinguish.

8. Sea-ice navigation relied on micro-patterns in the landscape.

Inuit navigators read subtle shifts in snow texture, wind-carved ridges and ice tone to determine safe passages. These cues act like a natural map. The skill requires decades of experience and deep environmental memory. Travelers could determine wind direction, ice thickness and hidden currents with a level of accuracy comparable to modern instruments.

This method allowed long-distance movement across unpredictable surfaces. The knowledge was refined collaboratively, passed through generations that relied on survival routes no outsider could detect.

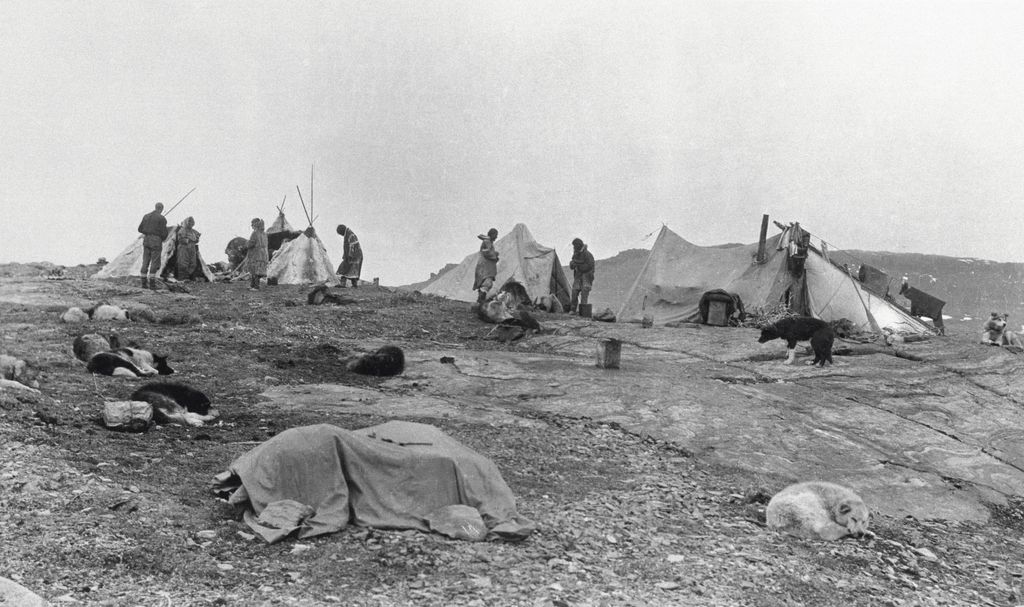

9. Flexible housing systems adapted instantly to conditions.

Unlike permanent structures, Inuit camps could be assembled or dismantled quickly in response to weather or wildlife movement. Tents made from hides offered ventilation in summer, while snow houses provided insulation in winter. Families moved with seasonal cycles, optimizing resource use and reducing exposure to risk. The flexibility reflects an advanced understanding of energy conservation and environmental balance.

These structures worked in harmony with the landscape. Instead of fighting the elements, they aligned with them, preserving energy that would otherwise be spent enduring harsh conditions.

10. Community knowledge networks functioned like scientific research.

Survival depended on shared innovation. Skills, observations and refinements moved through families and across regions, evolving with each generation. This collaborative approach mirrors modern scientific methodology, where data is tested, corrected and preserved. The consistency found across technologies suggests a long tradition of collective problem solving.

This network ensured that improvements spread quickly. No single innovation stood alone. Each tool, shelter and practice grew from the same principle: knowledge is a resource that strengthens when shared.