A direct stare can quietly trigger danger.

Eye contact is not universal language in nature. For many wild animals, a steady stare signals threat, challenge, or intent to dominate. In forests, savannas, deserts, and waterways, biologists repeatedly warn that human gaze can escalate encounters fast. Knowing when to look away can quietly reduce risk, prevent charges, and keep brief encounters from turning dangerous for both people involved.

1. Mountain lions read eye contact as direct challenge.

In western North America, mountain lions assess threats silently. Prolonged eye contact mimics predatory focus and can trigger stalking behavior during daylight hikes or dusk encounters near trails, according to the National Park Service across public lands each year widely.

Looking away while backing slowly reduces escalation. Maintaining peripheral awareness helps avoid sudden movement, which lions interpret as weakness. Most confrontations reported in California and British Columbia end without contact when humans break gaze and appear larger to predators nearby.

2. Brown bears treat staring as an aggressive signal.

In Alaska and parts of Eastern Europe, brown bears communicate dominance through posture and gaze. Sustained eye contact can escalate bluff charges during surprise encounters on rivers or berry patches, as stated by Alaska Department of Fish and Game officials.

Avoid staring while speaking calmly and slowly backing away. Fixed gaze suggests competition over space or food. Many recorded injuries occur when hikers freeze and lock eyes instead of creating distance and reducing perceived threat cues in wild settings alone.

3. African elephants interpret staring as dominance testing.

Across African savannas, elephants rely on visual signals to assess rank. Direct eye contact can provoke mock charges, especially near calves or waterholes, as reported by World Wildlife Fund field researchers during dry seasons when resources tighten quickly there regionally.

Lowering your gaze and increasing distance reduces perceived threat. Elephants often pause and reassess once the stare ends. Many dangerous encounters documented in Kenya and Botswana involved prolonged visual fixation during close range photography near herds in open reserves there.

4. Gorillas perceive eye contact as immediate challenge.

In Central African forests, gorillas use gaze to signal intent. Staring can trigger chest beating or bluff charges, particularly from silverbacks protecting groups. Encounters most often occur during guided treks in Rwanda and Uganda where tourism brings humans close regularly.

Looking aside while staying still reduces tension. Gorillas frequently disengage when humans break eye contact. Rangers emphasize neutral posture and slow movements to avoid escalating situations in dense vegetation where escape routes are limited during close encounters on trails nearby.

5. Chimpanzees react defensively to prolonged human staring.

Chimpanzees use intense eye contact to assert hierarchy. In forests of Tanzania and West Africa, staring may provoke screaming displays or charges, especially around food sources or infants during research or tourism encounters when group dynamics feel unstable suddenly nearby.

Averted gaze communicates non threat. Many primatologists advise watching indirectly while keeping body sideways. Several documented injuries occurred when visitors locked eyes during feeding times at forest edge sites across reserves where habituated groups forage near people daily seasonally there.

6. Wolves interpret staring as a territorial confrontation.

In North American and Eurasian ranges, wolves use eye contact to test rivals. Sustained staring can escalate defensive behavior if humans appear near dens or carcasses during winter when packs are stressed by food scarcity and heavy snow cover conditions.

Breaking gaze and increasing distance signals neutrality. Wolves typically retreat once threat perception drops. Rare aggressive incidents often involve prolonged observation at close range by people attempting photography or tracking during dawn or dusk periods in remote territories mostly alone.

7. Moose may charge when eye contact persists.

Across boreal forests and suburban edges, moose perceive staring as provocation. Eye contact during fall rut or spring calving can prompt sudden charges, particularly along roadsides in Alaska, Canada, and Scandinavia where humans frequently encounter animals at close range seasonally.

Looking away while increasing space lowers risk. Moose rely on early visual cues before acting. Many injuries happen when people stop to stare during roadside photography or yard encounters in snowy months across northern towns and park corridors frequently reported.

8. Bison respond aggressively to sustained human staring.

In Yellowstone and other plains parks, bison interpret staring as challenge. Direct eye contact can precede charges, especially when visitors approach too closely during summer calving season when herds occupy trails boardwalks and thermal basins frequented by crowds daily there.

Averted gaze and slow retreat reduce risk. Bison rely on visual distance to gauge threats. Most injuries occur after prolonged staring combined with attempts to photograph animals at close range by tourists during peak visitation months in large parks nationwide.

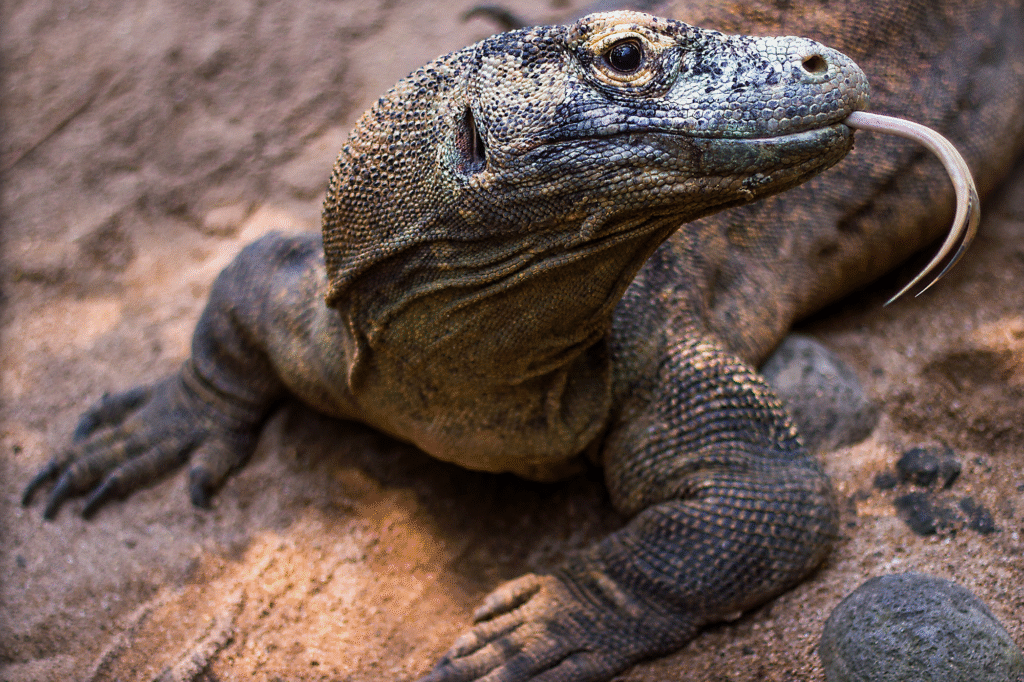

9. Komodo dragons interpret staring as prey focus.

On Indonesian islands, Komodo dragons use gaze to assess prey. Prolonged eye contact can trigger investigative approaches, especially around food scraps or injured animals near ranger stations where human presence alters feeding behavior patterns seasonally during dry periods there often.

Looking away and backing slowly reduces interest. Rangers advise minimizing eye contact while maintaining awareness. Several incidents involved tourists staring during guided walks on Rinca and Komodo islands when dragons were actively foraging near paths and campsites frequented by groups.

10. Saltwater crocodiles view eye contact as threat.

In northern Australia and Southeast Asia, saltwater crocodiles monitor eye movement closely. Staring can trigger defensive lunges near riverbanks, especially during nesting season or low tide when crocodiles are exposed and guarding territories close to human activity zones frequently observed.

Averted gaze combined with distance reduces risk. Crocodiles rely on stillness to judge threats. Many attacks occur after people linger and watch animals too closely from banks or boats in estuaries rivers and mangrove systems across tropical regions worldwide today.

11. Cassowaries interpret staring as territorial aggression behavior.

In northeastern Australia, cassowaries rely on vision to assess threats. Direct staring can provoke charges, especially near feeding sites or during breeding season in rainforest edges where human development intersects wildlife corridors and fruit availability shifts seasonally there often now.

Looking down and retreating calmly reduces risk. Cassowaries often disengage once eye contact ends. Injuries frequently involve people stopping to stare while photographing birds on walking tracks in coastal Queensland reserves during busy tourist seasons when encounters rise sharply each.

12. Cobras react defensively to sustained direct gaze.

In South Asia and parts of Africa, cobras use visual focus to assess threats. Staring can prompt hood displays or strikes, especially during accidental encounters near homes or fields where human activity overlaps snake habitat during warm seasons frequently reported.

Averted eyes and slow retreat reduce escalation. Snakes often strike when they perceive focused attention. Many bites occur after people freeze and stare instead of creating distance during sudden encounters on paths farms and village edges across regions seasonally there.