Near Göbekli Tepe, meaning begins to take form.

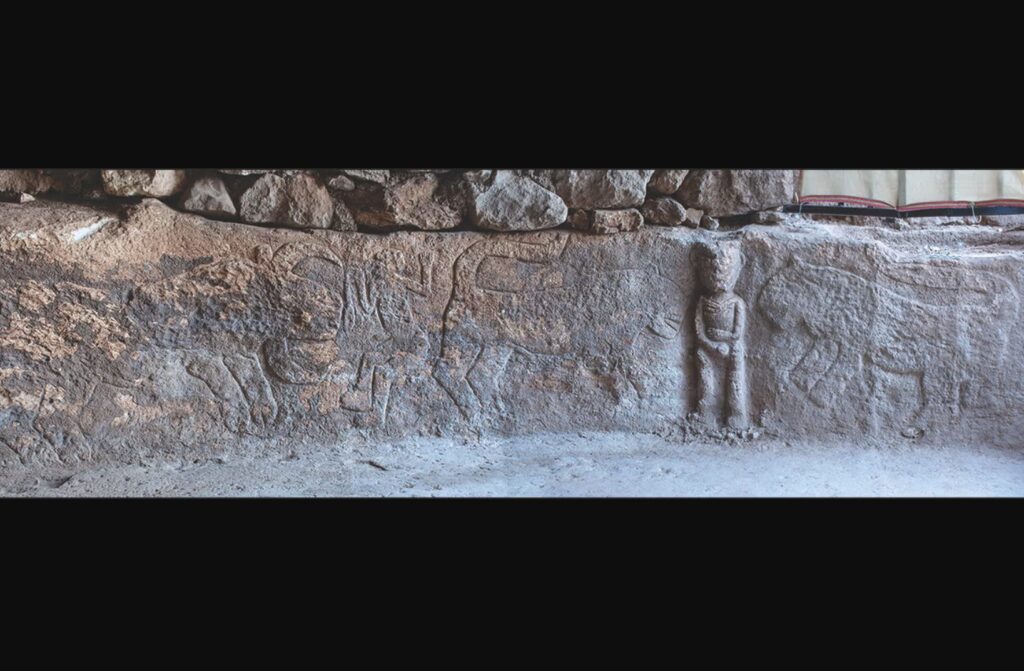

On a limestone wall in southeastern Turkey, a scene carved eleven millennia ago is forcing archaeologists to rethink when humans first began telling stories. Found near Göbekli Tepe, the relief does not depict a single animal or symbol but an interaction between figures. This was not decoration. It was narrative. Long before writing, farming, or cities, someone carved meaning into stone, revealing a moment when imagination crossed into shared human storytelling.

1. The carving was discovered near the Göbekli Tepe complex.

The relief was uncovered at Sayburç, a small archaeological site roughly thirty miles from Göbekli Tepe in Şanlıurfa Province. Archaeologists identified the carving in a communal structure dated to around 9000 BCE. According to Archaeology Magazine, the stone panel depicts multiple figures interacting within a single scene rather than isolated symbols.

This proximity matters because Göbekli Tepe is already known as the world’s oldest monumental ritual site. The Sayburç carving expands that cultural landscape. It suggests a broader regional tradition of symbolic expression rather than a single extraordinary location.

2. The scene shows multiple figures engaged in action.

Unlike earlier carvings that focus on animals or abstract motifs, this relief shows human figures facing animals in a shared space. One human appears to confront a large predator while another figure stands nearby. According to National Geographic, this interaction marks the earliest known example of a narrative scene carved by humans.

The figures are arranged deliberately, guiding the viewer’s eye across the stone. This layout implies intention beyond symbolism. It suggests the carver wanted others to understand an event or idea, not just admire a form.

3. Researchers believe it represents a shared communal story.

Archaeologists interpret the carving as evidence of storytelling meant to be seen and discussed by others. The panel was built into a bench like structure where people likely gathered. As reported by Smithsonian Magazine, the scene may represent myth, memory, or a moral lesson shared within the community.

This shifts how early cognition is understood. The carving implies humans were already creating shared narratives before agriculture took hold. Storytelling appears as a foundation of social bonding, not a byproduct of later civilization.

4. The carving predates writing by thousands of years.

The Sayburç relief was created at least six thousand years before the earliest known writing systems. There are no letters or numbers, only images arranged with intent. This shows that humans were communicating complex ideas visually long before formal language systems existed.

The scene functions like a frozen moment in a story. It relies on shared understanding rather than text. This challenges the assumption that storytelling requires writing to exist.

5. Stone Age creativity appears far more advanced.

For decades, Stone Age art was described as simple or symbolic. This carving undermines that view. It shows planning, abstraction, and narrative logic. The figures are proportioned and placed with care, not randomly etched.

This level of creativity suggests early humans were capable of complex thought much earlier than believed. Their mental worlds were rich with meaning, memory, and imagination. Art was already serving as communication.

6. The relief likely held ritual significance.

The carving was placed in a communal architectural setting, not hidden or private. This suggests it played a role in shared rituals or gatherings. The figures may reference ancestral stories, spiritual beliefs, or social rules.

Ritual spaces amplify meaning. By embedding the story into stone architecture, the community ensured it endured across generations. The carving became part of lived experience, not just visual art.

7. Animals appear as characters rather than decoration.

Predatory animals in the carving face humans directly. They are not background elements. This positioning implies symbolic roles such as danger, power, or transformation. Animals appear to participate in the story.

This reflects a worldview where humans and animals shared a meaningful relationship. Nature was not separate from human life. It was central to identity, belief, and survival.

8. The discovery reshapes early human timelines.

The carving forces archaeologists to push back the timeline for narrative thinking. Storytelling was once linked to settled societies. This evidence shows it emerged among hunter gatherers.

That realization changes how culture is defined. Creativity and shared meaning did not wait for cities. They helped create the conditions that made civilization possible.

9. Göbekli Tepe’s region now appears culturally unified.

The Sayburç relief supports the idea that Göbekli Tepe was part of a larger symbolic network. Similar motifs appear across nearby sites. This suggests shared beliefs across communities.

Rather than isolated innovation, the region reflects cultural exchange. Ideas moved between groups long before written records. Storytelling connected people across landscapes.

10. The carving marks the birth of recorded imagination.

This relief stands as the earliest known human story preserved in stone. It captures imagination made permanent. Someone wanted others to remember, reflect, and understand.

In that act, creativity became communal. The carving bridges thought and memory. It marks the moment when humans began recording not just survival, but meaning itself.