Genetic clues reopen an old coastal mystery.

Along California’s central coast, the Chumash built one of North America’s most advanced maritime cultures. Far across the Pacific, island societies mastered long distance ocean travel centuries before European contact. For years, similarities between these worlds were treated as coincidence. New genetic analysis has added weight to older questions, suggesting limited but meaningful contact across the Pacific. The findings do not rewrite history outright, but they complicate it, revealing how connected the ancient world may have been.

1. Genetic markers suggest unexpected ancestral connections.

Recent genetic analysis identified markers that appear in both Chumash descendants and certain Pacific Island populations. These shared segments are rare and do not align neatly with known migration patterns across the Americas. Their presence suggests contact that falls outside traditional models of isolation.

The study focused on specific haplotypes rather than broad ancestry claims. According to Nature, researchers emphasized that the genetic overlap is limited but statistically significant, pointing toward historical interaction rather than shared continental origin or modern admixture.

2. The findings challenge long accepted migration models.

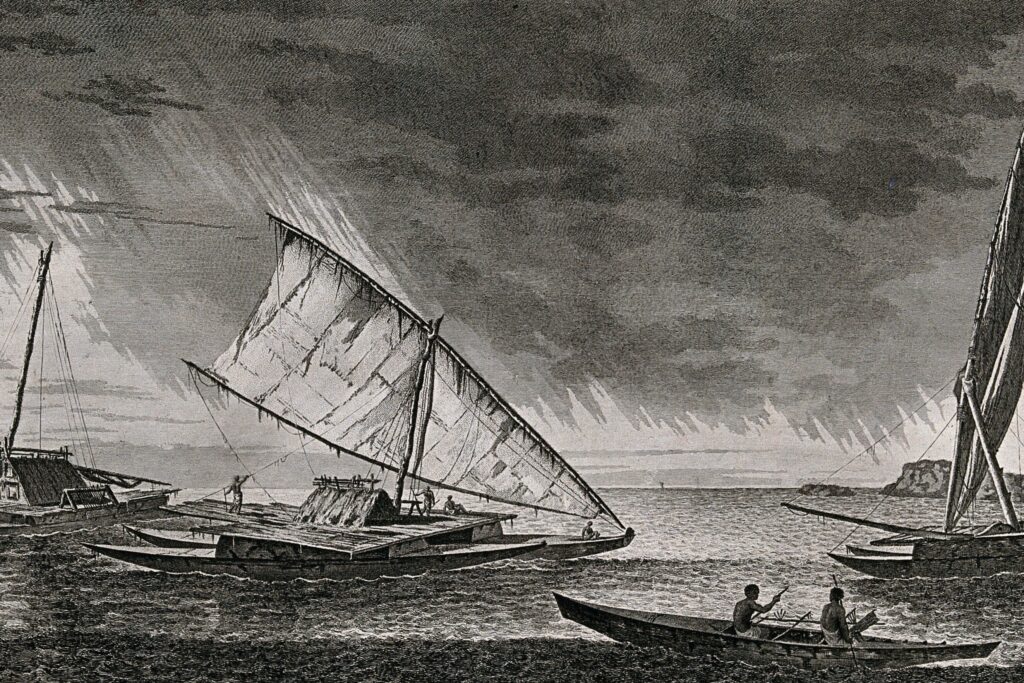

For decades, migration theories focused almost entirely on land routes through Beringia. Ocean travel across the Pacific was considered implausible for contact with coastal North America. The genetic data introduces a new variable into that framework.

Rather than replacing existing models, the evidence adds complexity. It suggests supplemental contact alongside established migration paths. As reported by Science Advances, the genetic signal aligns more closely with episodic interaction than large scale population movement, challenging assumptions without discarding them entirely.

3. Maritime technology supports possible ocean contact.

The Chumash were exceptional seafarers, building plank canoes capable of open water travel. Pacific Islanders developed vessels designed for long ocean crossings using stars, currents, and wind patterns. These parallel traditions raise practical questions about feasibility.

When combined with genetic evidence, maritime capability becomes harder to dismiss. As stated by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, technological skill plays a critical role in evaluating contact hypotheses, especially when genetic markers suggest interaction rather than isolation.

4. Cultural similarities alone were once dismissed.

Anthropologists previously noted similarities in fishing methods, shell bead use, and . These observations were often treated cautiously, attributed to independent development rather than contact.

Without genetic support, such comparisons remained speculative. The new DNA findings do not prove cultural exchange outright, but they reopen older observations that were set aside. Cultural parallels now sit alongside biological data rather than standing alone.

5. The genetic signal appears limited and specific.

Importantly, the shared genetic markers do not appear across all Chumash or Pacific Island populations. They are localized, suggesting contact events rather than widespread blending. This pattern fits small scale interaction rather than migration.

Such specificity reduces the likelihood of coincidence or contamination. It also points toward brief encounters that left lasting traces. Limited contact can still reshape understanding without implying sustained settlement or domination by either group.

6. Timing remains the most difficult question.

Determining when contact occurred is challenging. Genetic data can indicate relatedness but struggles to pinpoint exact dates. Archaeological layers and oral histories offer clues but no definitive timeline.

Most estimates place interaction within the last several thousand years, after maritime technologies matured on both sides of the Pacific. The uncertainty keeps conclusions cautious, emphasizing possibility over certainty while still acknowledging the significance of the signal.

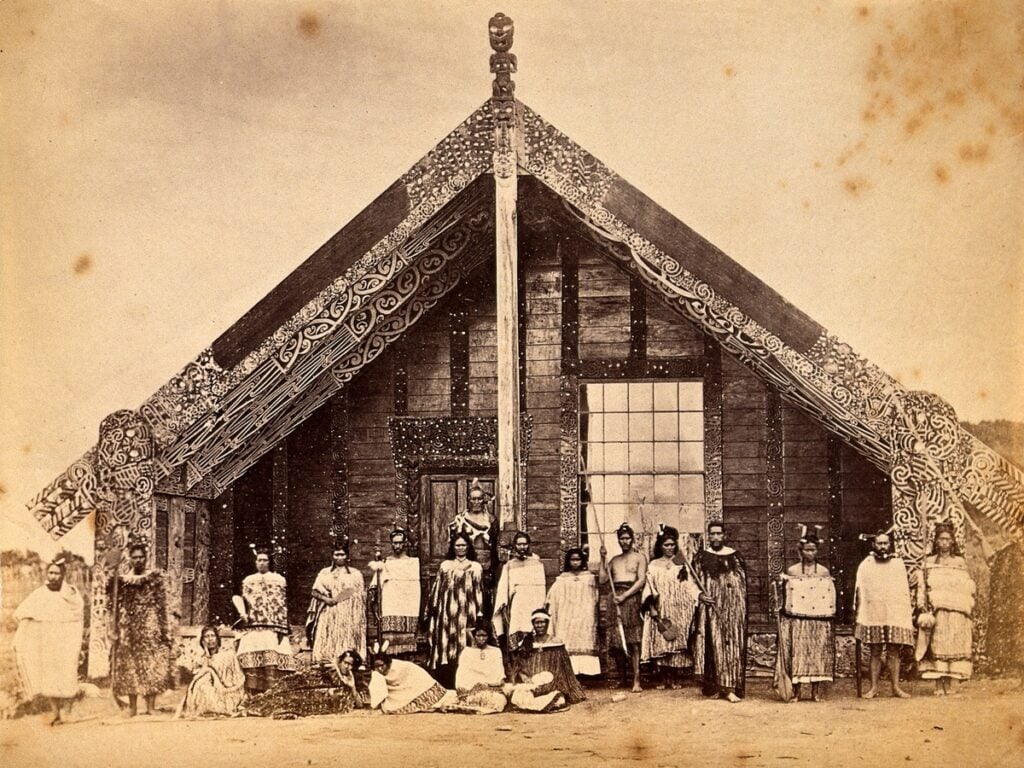

7. Indigenous histories provide important context.

Chumash oral traditions emphasize the ocean as a connector rather than a barrier. Stories describe long journeys, trade, and knowledge exchange along the coast and beyond. These narratives were often sidelined in academic interpretation.

While oral history is not genetic evidence, it frames how communities understood their world. The DNA findings give new weight to Indigenous perspectives that long suggested broader connections across water rather than isolation.

8. The study avoids claims of direct ancestry.

Researchers were careful not to suggest that Pacific Islanders are ancestors of the Chumash or vice versa. The genetic overlap represents contact, not origin. This distinction matters for both scientific accuracy and cultural respect.

Framing the findings as interaction rather than lineage avoids oversimplification. It acknowledges complexity without collapsing distinct histories into a single narrative. Precision here protects against sensationalism while preserving significance.

9. Broader implications extend beyond California.

If limited trans Pacific contact occurred along the California coast, it raises questions about other coastal societies. Similar interactions may have gone undetected due to lack of genetic sampling or preservation.

The study encourages reexamination of coastal archaeology with fresh assumptions. Ocean currents, not land borders, may have shaped more human interaction than previously acknowledged, especially among skilled maritime cultures.

10. Ancient oceans were not the barriers assumed.

The combined genetic, technological, and cultural evidence suggests ancient oceans functioned as pathways rather than walls. Even rare contact events can leave measurable traces thousands of years later.

The Chumash and Pacific Islanders did not exist in sealed worlds. Their connection, however limited, reshapes how ancient human networks are understood. History appears less isolated, more dynamic, and more connected than once believed.