Water never forgot where it once belonged.

Long before canals, pumps, and crop grids, California’s Central Valley was shaped by water moving on its own schedule. Tulare Lake rose and fell with snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada, sometimes stretching across the horizon, sometimes retreating into wetlands and marsh. Engineers later erased it from maps and memory, confident it was gone for good. But geography does not forget. In recent years, storms have forced Tulare Lake back into view, revealing how temporary control can be.

1. Tulare Lake once dominated California’s Central Valley.

At its fullest, Tulare Lake covered more than 800 square miles, making it the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. Fed by four major rivers, the Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern, the lake expanded during wet periods and slowly contracted during droughts. Its boundaries were never fixed, shifting with seasonal runoff and long climate cycles rather than human planning.

This variability was not a flaw but a function. The lake acted as a massive natural reservoir, absorbing floodwaters and releasing them gradually. According to the United States Geological Survey, Tulare Lake stabilized regional hydrology by buffering extreme runoff, reducing downstream flooding while sustaining wetlands across the valley floor.

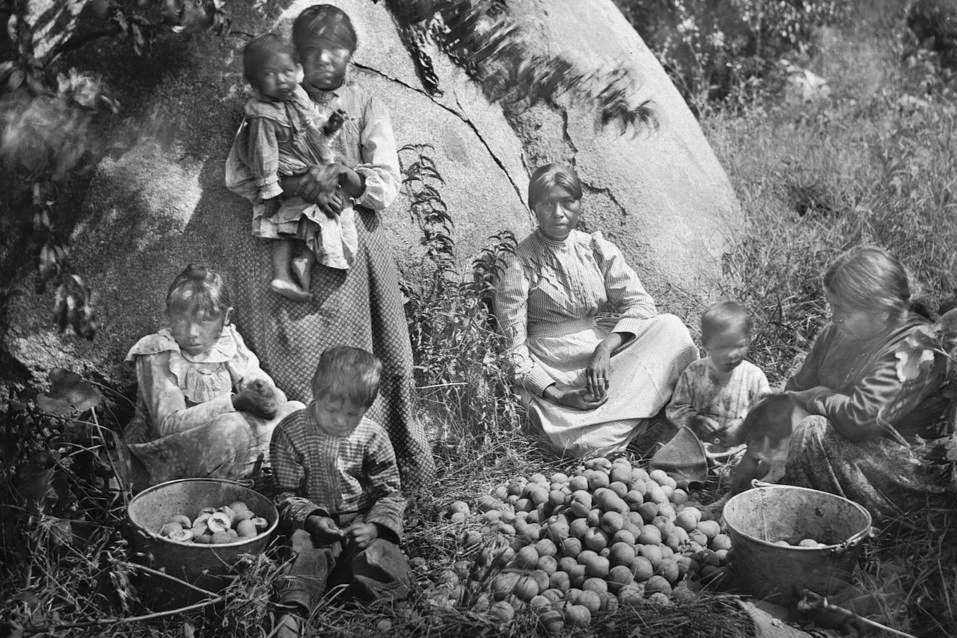

2. Indigenous communities adapted to the lake’s shifting nature.

For thousands of years, Yokuts and neighboring Indigenous groups lived with Tulare Lake rather than attempting to confine it. Villages moved as shorelines shifted, and livelihoods followed seasonal abundance. Fish, waterfowl, tule reeds, and edible plants formed a reliable food system rooted in ecological knowledge rather than permanent infrastructure.

The lake supported trade routes linking inland California to coastal regions. Canoes, fishing tools, and seasonal camps reflected adaptation rather than resistance. As stated by the California Department of Water Resources, Indigenous land use around Tulare Lake demonstrated an understanding of flood cycles that allowed sustainable living without draining or dominating the basin.

3. Early settlers underestimated the lake’s persistence.

When American settlers arrived in the nineteenth century, Tulare Lake appeared manageable during dry years. Farms and towns were built along its margins, assuming the water would remain predictable. That assumption collapsed during major flood events, especially in the 1860s, when heavy rains refilled the basin entirely.

Water remained for years, turning fields into marsh and settlements into islands. These floods were not anomalies but returns to long established patterns. As reported by Smithsonian Magazine, historical accounts show Tulare Lake repeatedly resurfaced during wet cycles, revealing how short settlement timelines were compared to geological memory.

4. Large scale engineering deliberately drained the basin.

By the late nineteenth century, efforts intensified to eliminate Tulare Lake permanently. Rivers feeding the basin were diverted into canals, levees were raised, and water was redirected toward irrigation networks. The lakebed was transformed into farmland through constant mechanical intervention.

This process did not remove the basin itself, only the water. The transformation depended on continuous control, with pumps and levees replacing natural flow. Draining Tulare Lake was celebrated as progress, but it required ongoing effort to maintain the illusion that the lake no longer existed.

5. Agriculture imposed rigid water schedules on flexible land.

Once converted to farmland, the former lakebed depended on precise irrigation timing. Crops demanded consistent water delivery, leaving no room for natural flooding or seasonal overflow. Rivers were confined, straightened, and regulated to meet agricultural schedules rather than ecological ones.

This rigidity increased vulnerability. When storms exceeded capacity, water returned to the lowest ground available. The land beneath farms had not changed, only the expectation placed upon it. Tulare Lake’s basin remained intact beneath the grid of fields.

6. Groundwater pumping destabilized the former lakebed.

As surface water became over allocated, groundwater pumping intensified across the region. Aquifers dropped dramatically, causing land subsidence that damaged canals, levees, and roads. The ground itself sank, reducing the ability to move or store water safely.

Subsidence weakened infrastructure designed to keep the basin dry. Ironically, the effort to extract more water increased flood risk. The drained lakebed became less resilient over time, not more stable, exposing long term consequences of replacing natural storage with mechanical systems.

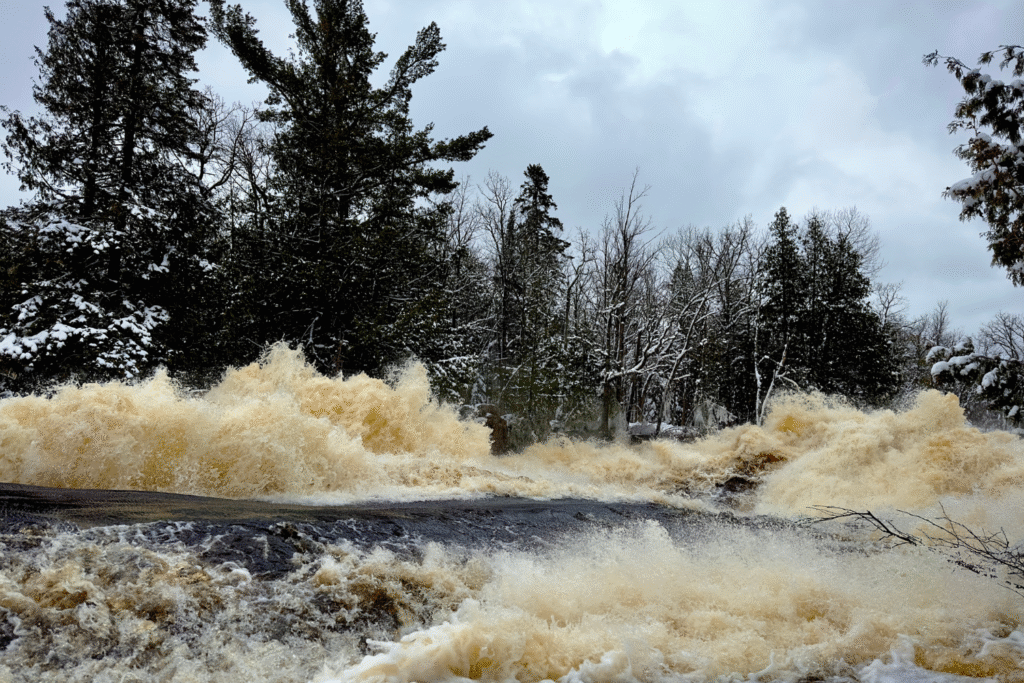

7. Recent storms overwhelmed engineered defenses.

Beginning in 2023, repeated atmospheric rivers delivered record rainfall and snowmelt to California. Rivers swelled beyond capacity, levees failed, and water flowed downhill according to gravity rather than policy. Tulare Lake began to re form in the exact place it once occupied.

Fields flooded, highways closed, and entire communities were displaced. The lake’s return followed historical contours mapped long ago. The basin accepted water as it always had, regardless of modern boundaries or ownership.

8. Wildlife returned with remarkable speed.

As water pooled, birds arrived almost immediately. Migratory species used the flooded basin as resting and feeding grounds, mirroring patterns recorded generations earlier. Fish appeared in channels and lowlands, carried by rivers reclaiming old routes.

This rapid response demonstrated ecological memory. Even temporary water restored functions that had lain dormant. The land responded as if the lake had merely been paused, not erased, revealing how resilient natural systems remain when conditions briefly return.

9. Flooding exposed the limits of permanent control.

Despite decades of infrastructure, pumps and levees failed under sustained pressure. Keeping the basin dry required constant energy and expense, which escalated rapidly during extreme weather. Once overwhelmed, the systems could not prevent water from reclaiming space.

The flooding revealed a fundamental truth. Engineering can redirect water temporarily, but it cannot remove geography. Tulare Lake’s basin remains the natural endpoint for runoff, regardless of land use or planning assumptions.

10. Climate change increases the likelihood of recurrence.

Warmer temperatures intensify storms and accelerate snowmelt, increasing the frequency of large runoff events. Climate models project greater extremes rather than stable patterns, raising the odds that Tulare Lake will continue to reappear.

This volatility favors natural basins that can absorb overflow. Rigid systems struggle under unpredictability. The lake’s return may shift from rare disruption to recurring reality as climate conditions continue to change.

11. California must decide how to live with memory.

Tulare Lake presents a choice between constant resistance and adaptive planning. Restoring parts of the basin as managed flood zones could reduce damage while supporting ecosystems. Ignoring history guarantees repetition.

Water does not forget where it belongs. The question is whether California will continue forcing it away, or finally design around the landscape that keeps reminding us what it once was.