Two discoveries rewrote Britain’s coastal past.

Along Britain’s eroding coastline, storms and shifting cliffs have a way of revealing what time tried to hide. In recent years, chance discoveries have exposed objects separated by millions of years yet bound by geography. One involved human hands, metal, and intent. The other belonged to a reptile that ruled ancient seas long before people existed. Found within miles of one another, these discoveries forced archaeologists and paleontologists to look twice at familiar shores. Britain’s coast turned out to be less predictable than anyone expected.

1. Storm erosion exposed artifacts buried for centuries.

After heavy winter storms battered the English coast, exposed sediment layers revealed metal glinting beneath collapsed cliffs. Local detectorists and archaeologists responded quickly, documenting coins and worked objects before tides reclaimed them. According to the British Museum, coastal erosion has become a leading factor in recent accidental discoveries.

The timing mattered. Without rapid reporting, saltwater would have damaged surfaces beyond study. Each object helped reconstruct trade, wealth, and movement along Britain’s shoreline. What first looked like scattered debris soon revealed deliberate burial, suggesting urgency, fear, or ritual rather than simple loss during travel.

2. The hoard reflected wealth from a volatile era.

Analysis showed the treasure dated to a period marked by political instability and shifting power. Coin composition and iconography pointed to regional authority rather than centralized rule, as reported by the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

That detail reframed the find. Instead of a merchant’s savings, the hoard likely represented emergency concealment during conflict. Buried close to the sea, it suggests coastal routes were lifelines and escape paths. The objects froze a moment of decision, capturing how people responded when order weakened and survival demanded quick, silent choices.

3. Cliff collapses also revealed something far older.

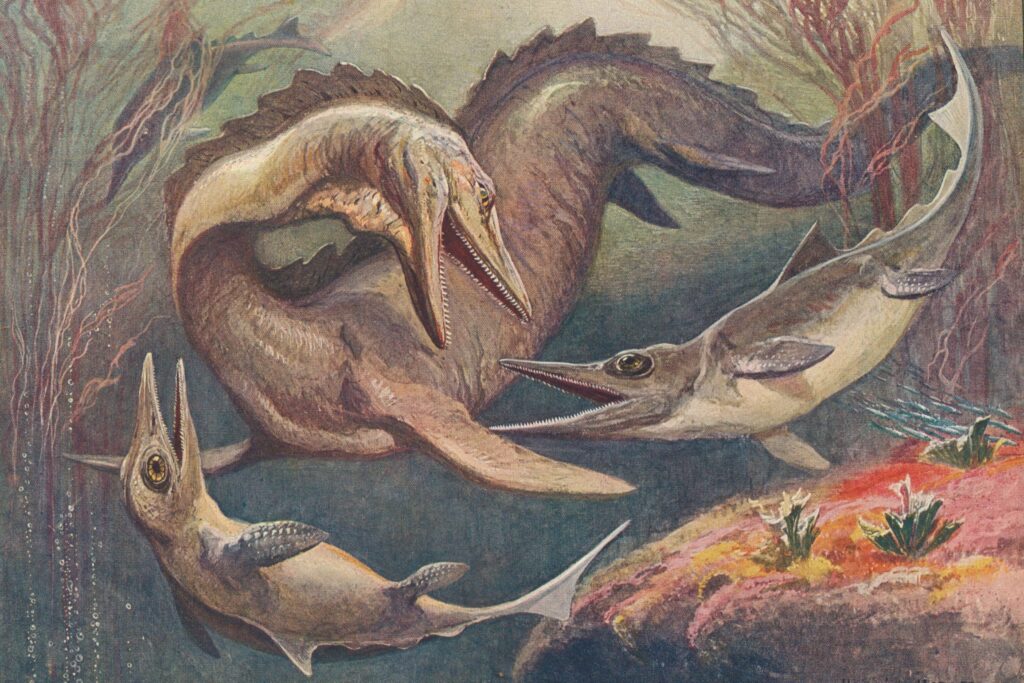

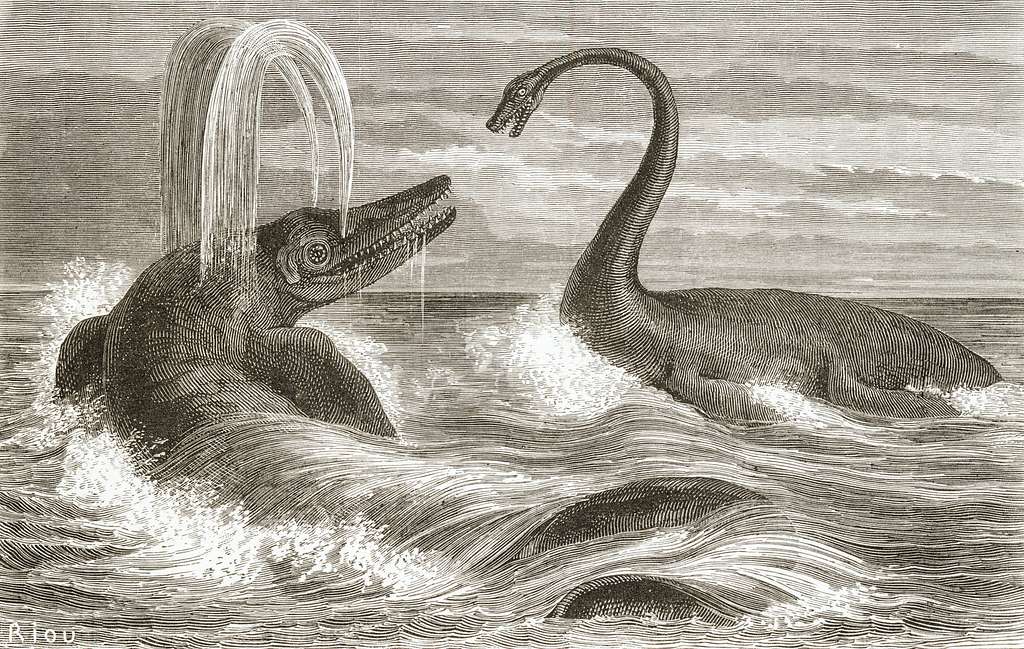

Not far from the treasure site, a separate cliff fall exposed massive vertebrae embedded in shale. Paleontologists recognized the shape immediately. It belonged to an ichthyosaur, a marine reptile that dominated Jurassic seas, as discovered by researchers affiliated with the Natural History Museum.

The scale surprised even seasoned experts. Measuring more than twenty meters, the specimen ranked among the largest marine predators ever documented. Its preservation was unusually complete, offering rare insight into anatomy. Britain’s coast had revealed not only human history but a reminder of oceans that vanished long before memory.

4. The sea dragon once hunted in warm shallow waters.

During the Jurassic period, much of what is now Britain lay beneath warm, shallow seas. Ichthyosaurs thrived there, feeding on fish and cephalopods with speed and precision. The newly uncovered skeleton confirmed that these waters supported giants.

Its size implies a stable, productive ecosystem capable of sustaining massive predators. Teeth structure and bone density suggest an animal built for endurance rather than quick ambush. This discovery strengthened the idea that ancient British seas rivaled modern oceans in biological richness and complexity.

5. Proximity of finds raised difficult interpretive questions.

Finding human treasure and prehistoric remains so close together forced researchers to confront scale in new ways. Millions of years separated the objects, yet erosion erased that distance in a single season. The coast collapsed time.

This overlap challenged how sites are protected. Archaeology and paleontology often operate separately, but Britain’s shoreline does not respect academic boundaries. Each storm reshapes priorities, making cooperation essential. What appears as loss through erosion can also become a fleeting window into layers of history stacked tightly together.

6. Local residents became first witnesses to history.

In both cases, discoveries began with ordinary people walking familiar paths. Dog walkers, hobbyists, and fossil hunters noticed shapes that felt wrong for modern debris. Their decisions to report instead of collect preserved critical context.

That trust mattered. Without coordinates and stratigraphic notes, both finds would have lost scientific value. The episodes highlighted how public awareness plays a growing role in heritage protection. Britain’s coast depends on many eyes, not just institutions, to catch moments before the sea erases them again.

7. Coastal erosion accelerated discovery and destruction.

Rising sea levels and stronger storms are speeding up cliff retreat across Britain. While this exposes buried material, it also threatens to destroy it quickly. The balance between discovery and loss grows tighter each year.

Researchers now race against time. Excavation schedules shorten, funding decisions shift, and emergency surveys become routine. These finds illustrated the urgency. Without rapid response, both the treasure and the sea dragon would have fragmented into the surf, leaving only rumors behind.

8. Scientific methods preserved fragile evidence.

Once recovered, both finds required specialized conservation. Metals underwent desalination and stabilization, while fossil bones were reinforced to prevent cracking. Precision mattered at every step.

Laboratory work revealed details invisible in the field. Tool marks on coins, growth patterns in vertebrae, and mineral traces all added depth to the story. These processes turned raw discovery into usable knowledge, proving that careful handling matters as much as dramatic exposure.

9. Public reaction reshaped interest in coastal heritage.

News of the discoveries sparked renewed attention to Britain’s shoreline. Museums reported increased interest, and local councils reassessed monitoring strategies. The coast began to feel alive with possibility again.

This attention carried responsibility. Authorities balanced access with protection, knowing publicity can attract both curiosity and damage. Still, the finds reminded the public that history is not sealed behind glass. It lies underfoot, waiting for the right moment to surface.

10. Britain’s coast emerged as a layered archive.

Together, the treasure and the sea dragon reframed how Britain’s coastline is understood. It is not a boundary but a record, constantly edited by water and weather.

Each collapse rewrites the page. Human fear, ancient predators, forgotten seas all coexist within meters of one another. These discoveries did not just add facts. They altered perspective. Britain’s coast now reads less like a line on a map and more like a living archive, briefly open before the tide turns again.