An Indigenous system quietly influenced Western governance.

Centuries before modern constitutions were drafted, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy governed itself through a detailed political framework designed to stop cycles of violence and concentrate power responsibly. Known as the Great Law of Peace, this system emerged in what is now the northeastern United States and southern Canada, likely between the 12th and 15th centuries. When European colonists arrived, they encountered not fragmented tribes but a functioning, durable political union. Observers did not always understand it fully, but its principles lingered. Over time, they subtly reshaped how democracy itself would be imagined.

1. The Great Law created a lasting political union.

The Great Law of Peace unified five distinct nations into a single confederacy without erasing their sovereignty. Each nation retained control over its internal affairs while participating in shared decision making through a central council. This balance allowed cooperation without domination.

What made this union remarkable was its longevity. While many European alliances fractured within decades, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy endured for centuries. According to the National Museum of the American Indian, the system resolved disputes internally through diplomacy rather than force. This model demonstrated that political unity did not require centralized authority, an idea that later resonated with thinkers grappling with how independent states might coexist under a shared framework.

2. Leadership was limited by collective accountability.

Haudenosaunee leaders, known as sachems, did not rule by command. Their authority was conditional, grounded in service rather than dominance. Chiefs were expected to act in the interest of the people, and failure to do so carried consequences. Removal was not symbolic, it was real.

This structure directly contradicted European norms of hereditary or absolute rule. Power flowed upward from the people rather than downward from a throne. As reported by the Smithsonian Institution, colonial observers took note of how leaders were restrained by councils and clan mothers. The idea that leadership should be accountable, removable, and answerable became foundational to later democratic theory.

3. Decision making emphasized consensus over force.

Under the Great Law, decisions required broad agreement across nations. Debate was expected to be deliberate and respectful. Rushed outcomes were discouraged. The process favored patience over efficiency.

This emphasis on consensus reduced factionalism and limited tyranny by majority. According to research presented by the Library of Congress, early American thinkers observed these councils and contrasted them with adversarial European politics. The system demonstrated that governance could prioritize unity without suppressing dissent. That approach influenced later ideas about deliberative democracy, checks on power, and the importance of compromise in sustaining long term political stability.

4. Separate roles created a system of shared governance.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy distributed authority across multiple roles and councils. No single person or body controlled governance. Responsibilities were divided intentionally to prevent concentration of power.

Different councils handled diplomacy, war, and internal affairs. Clan structures provided oversight. This separation mirrored what later political philosophers would describe as checks and balances. While the systems are not identical, the underlying logic is similar. Power functions best when shared. This principle later became central to modern constitutional design, particularly in federal systems that sought to prevent authoritarian drift.

5. Women held decisive political authority.

Women were central to Haudenosaunee governance. Clan mothers selected chiefs, advised councils, and had the authority to remove leaders who violated the Great Law. Political legitimacy flowed through maternal lines.

This structure sharply contrasted with European political norms, where women were excluded from formal power. The Haudenosaunee system recognized women as guardians of continuity and moral authority. Their role ensured leadership remained aligned with communal values. This inclusion challenged colonial assumptions about governance and demonstrated that stable political systems could distribute authority across genders without undermining cohesion.

6. Individual freedom existed within collective responsibility.

The Great Law protected individual autonomy while emphasizing responsibility to the collective. People were free to speak, dissent, and participate in governance without fear of arbitrary punishment.

At the same time, personal actions were evaluated based on their impact on the community. This balance prevented both tyranny and fragmentation. Liberty did not mean isolation. It meant participation. This principle later echoed in democratic thought that framed freedom as inseparable from civic responsibility, shaping debates about rights, duties, and the social contract.

7. Law was memorized and transmitted communally.

The Great Law was preserved through oral tradition, wampum belts, and ceremonial recitation. Knowledge was not locked in texts accessible only to elites. It lived within the community.

This method ensured shared ownership of the law. Interpretation was collective rather than imposed. Memory became a civic duty. This approach parallels later democratic ideals of transparency and public engagement. Law was something people knew, not something done to them. Archaeological and ethnographic records show this system remained remarkably consistent across generations.

8. Peace was treated as a political achievement.

Peace under the Great Law was not passive. It required maintenance, restraint, and continuous dialogue. Governance existed to prevent violence before it erupted.

Conflict resolution mechanisms were embedded into political life. This reframed peace as an outcome of good governance rather than temporary absence of war. This concept influenced later thinking about the role of law in maintaining civil order. Government became a tool for preventing conflict, not merely responding to it, shaping modern expectations of political stability.

9. Diplomacy shaped colonial political imagination.

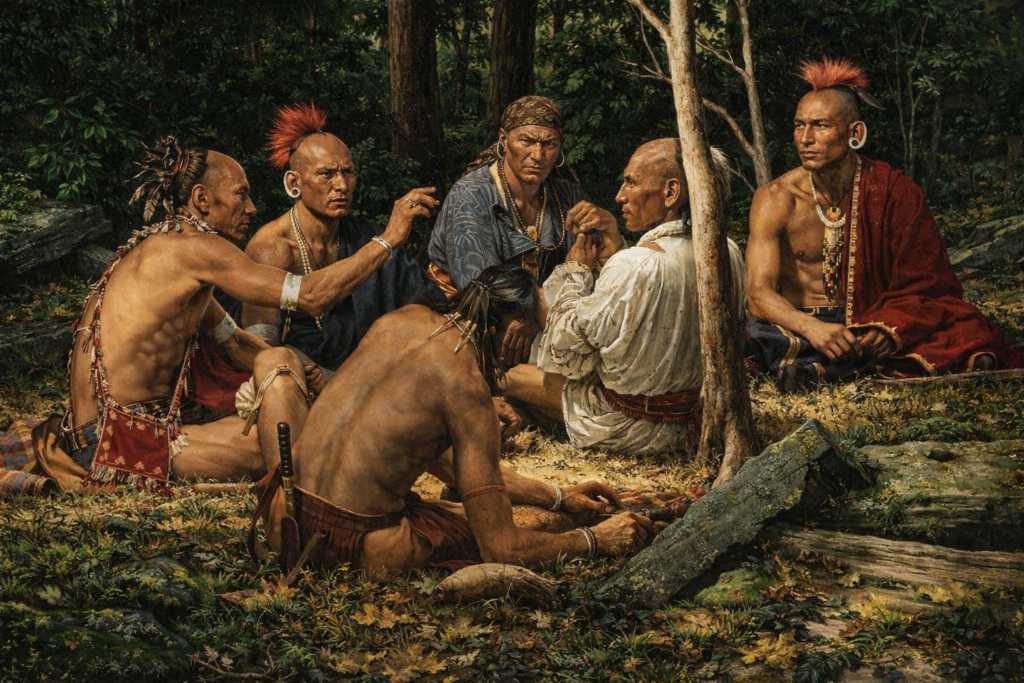

Colonial leaders regularly interacted with Haudenosaunee diplomats through treaties and councils. These encounters exposed them to unfamiliar political norms rooted in equality and mutual respect.

The confederacy negotiated as a sovereign entity, demanded accountability, and expected long term commitments. These experiences challenged European hierarchical assumptions. While ideas were adapted selectively, exposure mattered. Concepts of federalism, representation, and intergovernmental negotiation were shaped in part by sustained contact with Indigenous governance systems.

10. The influence was subtle but historically significant.

The Great Law of Peace was not copied directly into modern constitutions. Its influence was indirect, shaped through observation, dialogue, and adaptation.

Ideas such as union without domination, accountable leadership, shared power, and peace as governance filtered into Enlightenment thought. The system stands as evidence that democratic principles did not emerge in isolation. They were informed by long practiced Indigenous political traditions. Recognizing this influence broadens the story of democracy and restores depth to its global origins.