A controversial idea is forcing physicists to respond.

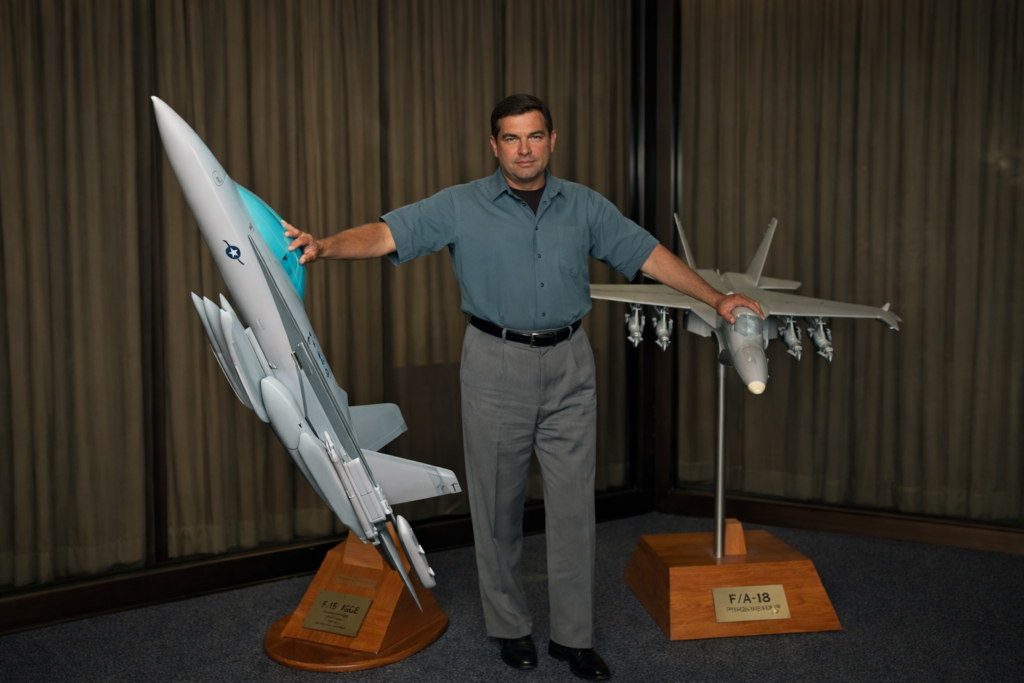

In late 2023 and through 2024, a claim began circulating well beyond engineering circles. Salvatore Pais, a former aerospace engineer whose work has previously drawn attention inside the U.S. defense research ecosystem, asserted that a new class of engineered systems could manipulate inertia itself. If correct, the implications would reach far beyond flight. Gravity, long treated as untouchable outside theory, would become something engineers could influence. Scientists are cautious, but they are no longer ignoring the claim.

1. Salvatore Pais argues inertia can be engineered directly.

Pais claims his work focuses on manipulating how matter interacts with the surrounding vacuum field. Rather than pushing against gravity, his approach aims to reduce inertial resistance, the property that makes objects resist motion. If inertia drops, lift requires far less force.

In interviews and technical filings, Pais has argued that extreme electromagnetic configurations can alter local physical conditions, according to reporting by The Drive. He emphasizes that the concept does not cancel gravity but changes how mass responds to it. Physicists remain skeptical, yet the claim is specific enough to provoke serious scrutiny rather than outright dismissal.

2. His work builds on unconventional physics concepts.

Pais’s ideas draw heavily from quantum field theory and vacuum energy models. He suggests that space itself is not empty, but structured, and that engineered systems can interact with that structure under precise conditions.

This framework overlaps with speculative physics but is not invented in isolation. Similar discussions appear in academic literature exploring zero point energy and spacetime structure. What makes Pais unusual is his insistence that these effects are not theoretical but experimentally approachable, as stated by Popular Mechanics. That assertion is where debate intensifies, separating cautious curiosity from sharp criticism.

3. Government patents brought the claims public attention.

Pais first gained widespread attention through a series of U.S. Navy related patents describing advanced propulsion and inertial mass reduction devices. The filings described craft capable of extreme acceleration without conventional propulsion.

The patents were initially dismissed as speculative. However, Navy officials later confirmed they were pursued seriously enough to justify legal protection, as reported by The New York Times. That confirmation did not validate the physics, but it did confirm institutional interest. Once government agencies appeared willing to engage, the scientific community could no longer ignore the claims entirely.

4. The proposed systems rely on extreme electromagnetic conditions.

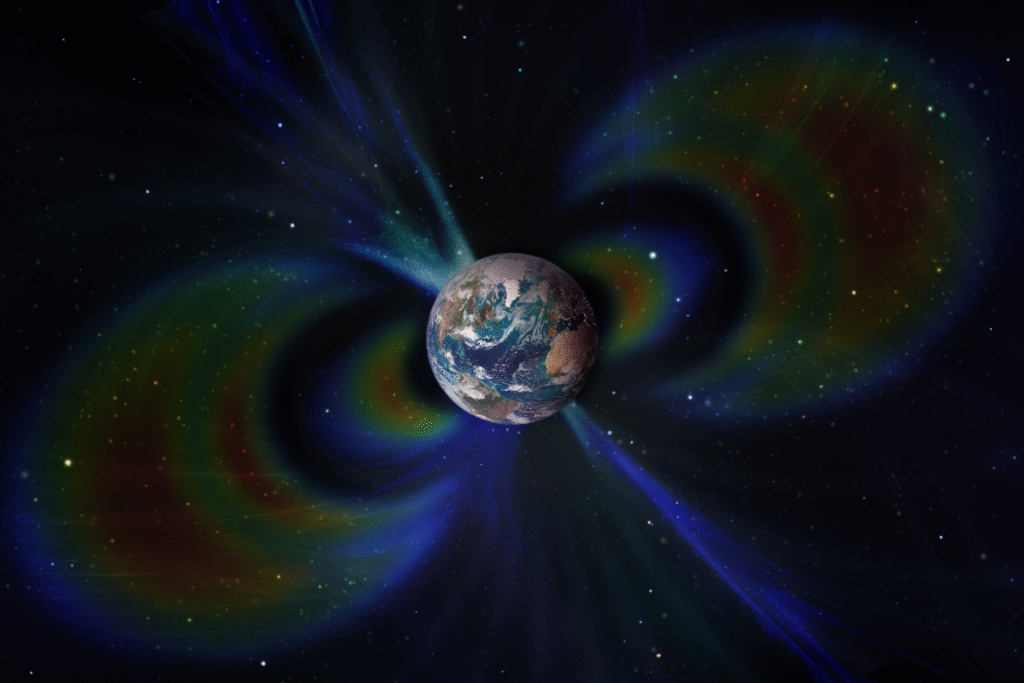

At the center of Pais’s concept are rapidly oscillating electromagnetic fields arranged in precise geometries. He argues that under certain frequencies and intensities, these fields can alter how mass couples to spacetime.

This is not anti gravity in the popular sense. No force pushes upward. Instead, resistance to motion drops. Engineers familiar with electromagnetic systems note that achieving such conditions would be extraordinarily difficult. The technical challenge alone makes the claim testable in principle, even if success remains uncertain.

5. Critics point to missing experimental verification.

The largest obstacle facing Pais’s claims is the absence of independently replicated experiments. No peer reviewed paper has yet demonstrated measurable inertial reduction under controlled conditions.

Physicists emphasize that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Mathematical consistency is not enough. Without reproducible data, skepticism remains the default. That said, critics also acknowledge that dismissing the idea outright would contradict scientific process. The correct response is verification or falsification, not silence.

6. Supporters argue the theory fits emerging anomalies.

A small number of researchers argue that unexplained experimental anomalies may align loosely with Pais’s framework. These include unusual force measurements in high energy electromagnetic setups and unexplained energy coupling effects.

While none prove inertial manipulation, supporters claim they justify deeper investigation. Engineering history is filled with phenomena that appeared impossible until instrumentation improved. From superconductivity to nuclear magnetic resonance, early skepticism did not prevent later breakthroughs. Pais’s supporters see his work as potentially occupying that early uncertain phase.

7. Aerospace implications drive intense interest.

If inertia could be reduced even slightly, the consequences for aerospace engineering would be profound. Launch systems would require far less energy. Aircraft could maneuver without extreme structural stress.

Defense analysts note that such capabilities would redefine mobility and logistics. This explains why government agencies have paid attention despite controversy. The interest does not confirm validity, but it shows that the potential payoff justifies careful evaluation rather than dismissal.

8. The claim challenges how gravity is treated practically.

Gravity itself remains well described by general relativity. Pais does not dispute that. His challenge is practical, not theoretical. He suggests engineers may not need to defeat gravity directly if they can change how objects respond to forces.

This reframing unsettles physicists because it blurs boundaries between fundamental theory and applied engineering. If correct, it would mean gravity is not bypassed, but effectively sidestepped through material interaction. That idea forces new questions about where engineering ends and physics begins.

9. Verification will determine whether history changes or closes.

Pais’s claims now sit at a crossroads. Either experiments will fail and the idea will fade, or measurable effects will force a reevaluation of long held assumptions.

What makes this moment unusual is not belief, but engagement. Engineers, physicists, and institutions are watching closely. Gravity itself may not be in danger, but the way humans interact with it could be. Science advances by confronting uncomfortable possibilities, and this one has reached the stage where it must be tested, not argued away.