A routine mission just became a medical test.

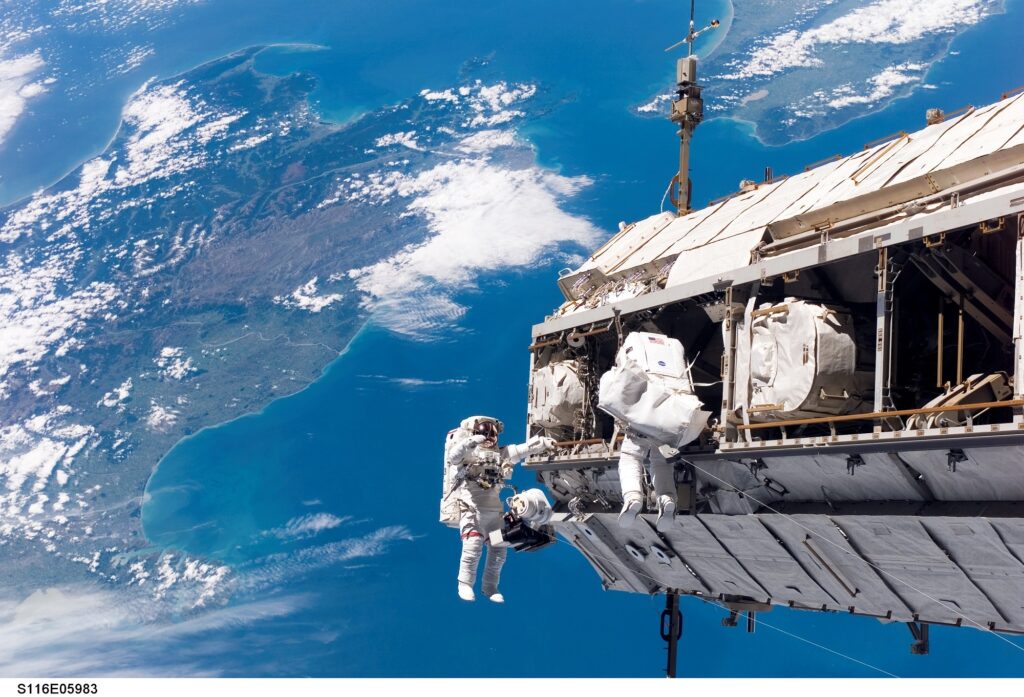

On January 7, 2026, NASA said a crew member aboard the International Space Station experienced a medical situation and was later described as stable. Within hours, the agency began weighing an early return that would cut a months long mission short, a rare move in the station’s quarter century history. The details are limited for privacy, but the ripple effects are loud. A single health concern is now shaping scheduling, spacewalk plans, and the way NASA thinks about risk when Earth is only a capsule ride away.

1. A medical concern forced an early return.

The decision started with a report from orbit on January 7, when one Crew 11 astronaut experienced a medical situation and the crew medical team began monitoring closely. NASA described the crew member as stable, but stability is not the same as resolution, especially when diagnostic tools in orbit are limited and treatment options are narrow.

NASA also treated the moment as operational, not dramatic, which is exactly why it is so revealing. The agency can keep a crew safe and still decide the safest move is leaving. It is the first real reminder in years that the station is not a hospital, it is a laboratory with a very small clinic. The early return discussion, including the decision to keep the astronaut’s identity private, was described in detail as reported by Reuters.

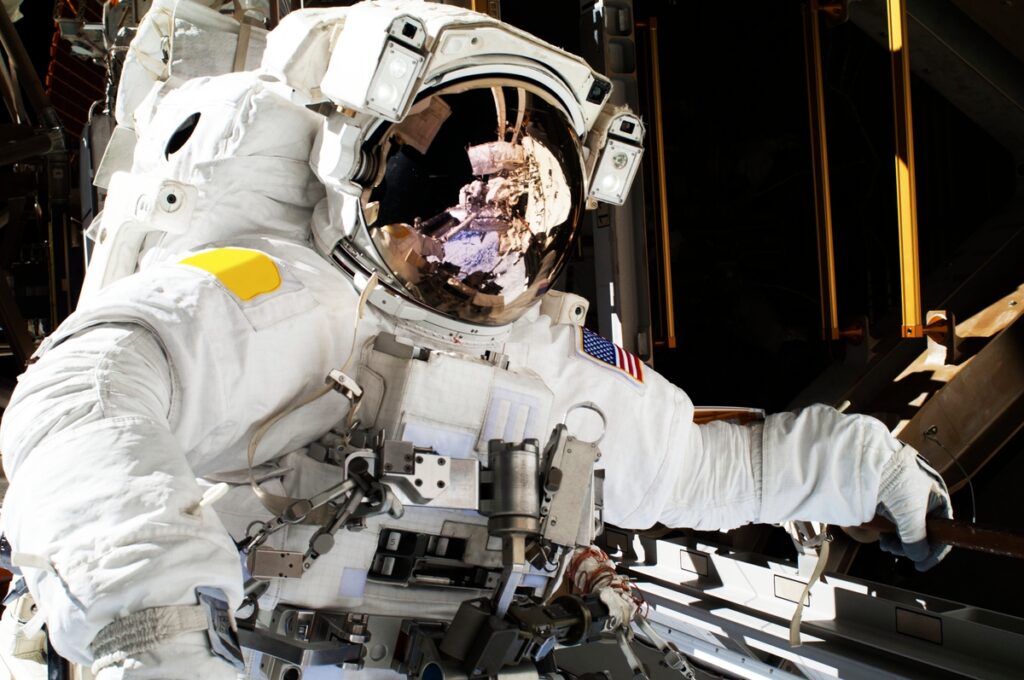

2. Canceling a spacewalk signaled higher caution.

When NASA canceled a planned spacewalk tied to station maintenance and prep work, it sent a clear signal. Spacewalks are choreographed, physically demanding, and risky even when everyone feels perfect. In a scenario where one crew member is under medical watch, NASA has to consider distraction, workload shifts, and the possibility of a second problem emerging.

A canceled spacewalk also reveals the quiet math of mission management. The station runs on routine, and a medical event breaks routine in a way that spreads. The remaining crew may be needed to assist, monitor, or simply conserve energy and focus. That changes what tasks are worth doing. NASA’s emphasis that the crew member was stable, while still shortening the mission, was outlined as reported by the Associated Press.

3. Privacy rules kept the illness details sealed.

People naturally want to know what happened and who is affected, but NASA’s astronaut medical privacy practices are strict. That means the public may never learn the diagnosis, even though the operational consequences are public and visible. The tension is that secrecy can breed speculation, even when it is ethically necessary.

In spaceflight medicine, privacy also protects future crews. Astronauts are screened intensely, and publicizing a medical issue could create stigma, career fears, and a chilling effect on reporting symptoms early. NASA needs crews to speak up fast, not hide discomfort until it becomes dangerous. The agency is trying to balance transparency with trust inside the astronaut corps, and that balance becomes harder when an early return is on the table, as stated by Scientific American.

4. Getting home fast is still complicated.

Even with a capsule docked and a return path mapped, bringing a crew home early is not like calling a rideshare. The vehicle has to be ready, weather at splashdown zones matters, recovery teams must be staged, and timing has to fit orbital mechanics. Every hour has to be planned around safety, not urgency alone.

There is also the question of what early return means for the remaining station timeline. A crew coming back early changes schedules for arrivals, handovers, and responsibilities. NASA and its partners have to keep the station staffed, maintain experiments, and avoid gaps in critical roles. In the background, mission planners are running scenarios, including what happens if the medical issue stabilizes further or worsens. The fact that NASA publicly discussed returning early shows how high the internal risk threshold rose.

5. Limited diagnostics in orbit drove the decision.

On Earth, a concerning symptom can be followed by imaging, labs, specialist consults, and rapid treatment changes. On the station, the medical toolkit is intentionally small. There are ways to monitor vital signs and manage many issues, but deep diagnostics are constrained by equipment, time, and the need to prioritize mission safety.

That limitation reshapes how NASA thinks about uncertainty. If doctors cannot confidently rule out serious causes, a conservative choice becomes more attractive. It is not only about the current symptom, it is about what the symptom could become in two days, or two weeks, with no intensive care available. This is why space agencies treat ambiguous medical situations as operational hazards. A stable astronaut can still be a reason to leave if the underlying cause is unknown and risk is trending upward.

6. Crew workload shifts can raise new risks.

Once one person is pulled toward medical monitoring, the rest of the crew has to absorb additional duties. That sounds manageable until you remember the station is a machine that demands constant attention. Maintenance, inspections, exercise protocols, communications, and experiments all compete for time, and fatigue is a real safety factor.

In a compressed situation, cognitive load becomes its own hazard. A tired astronaut can make a mistake on a simple procedure. A distracted crew can miss a subtle equipment warning. NASA is not only protecting the ill crew member, it is protecting everyone from cascading risk. That is the quiet theme of this story. Medical issues do not stay in one body. They change the whole system, including decision making, task sequencing, and the margin for error.

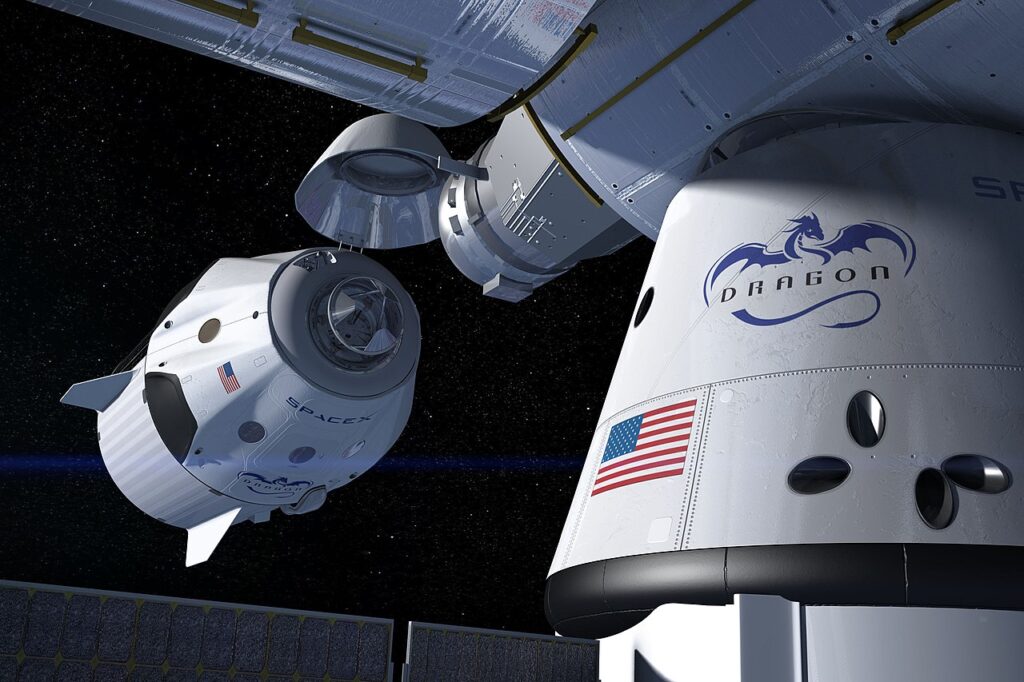

7. The return vehicle choice affects every option.

Crew returns are shaped by what spacecraft is available, how quickly it can undock, and where it can land. The vehicle has to support the crew during deorbit, reentry, and recovery, and it has to be configured for the right number of people. Even small changes in plan can require significant coordination.

Recovery is also part of the medical equation. If a crew member needs evaluation immediately, NASA has to plan for rapid transport after landing. That includes medical teams, equipment, and a smooth handoff to Earth based care. In public, this looks like a simple early return decision. In practice, it is a chain of readiness checks that must all align. The spacecraft is the lifeboat, but it is also a medical evacuation tool, and that dual role forces different planning than a routine end of mission.

8. This may reshape future medical protocols in space.

A high profile early return prompts reviews, even if the diagnosis stays private. NASA will look at whether current on orbit monitoring is sufficient, whether certain symptoms should trigger earlier intervention, and how to reduce uncertainty without overreacting. Space medicine is a field built on rare events, so each event gets studied intensely.

The broader context is that NASA is preparing for longer missions where early return is not possible, like lunar stays and eventual Mars planning. That makes every station medical event feel like a rehearsal, not just a one off problem. If an issue can force an early return from low Earth orbit, it raises uncomfortable questions about how crews will handle similar problems much farther away. That tension will likely push new training, new equipment, and more emphasis on diagnosing in place.

9. Better on board diagnostics could change everything.

One practical outcome may be investment in compact diagnostics that work reliably in microgravity. Portable ultrasound is already used in space, but future tools could expand to faster lab testing, improved imaging, and smarter monitoring that flags deterioration earlier. The goal would be to narrow uncertainty before it forces a mission level decision.

There is also a human factor. Astronauts could have more autonomy in assessing symptoms, guided by ground experts, without waiting for situations to escalate. That would protect privacy and reduce the need for public mission changes that invite speculation. A stronger medical toolkit in orbit does not just treat illness, it protects schedules, reduces risk for crewmates, and builds capability for deep space travel. In a way, this one event may accelerate the shift from spaceflight medicine as emergency response to spaceflight medicine as continuous precision care.