The sea has a hierarchy, and it bites.

The ocean is full of animals that hunt, but a small group rewrites the rules for everyone around them. Some dominate by speed, others by stealth, others by sheer mass and endurance. When these predators enter a bay, a reef edge, or an ice lead, prey do not just hide, they relocate, change feeding times, and sometimes stop making noise altogether. Here are ten predators that shape ocean life simply by showing up.

1. Orcas can clear a coastline quickly.

Orcas are not just large, they are strategic, and that changes how other animals behave long before an attack happens. In places like the Salish Sea, the Strait of Gibraltar, and Patagonia’s coastal shallows, their presence can push seals off haul out rocks and scatter schooling fish into tighter, more stressed formations. Even other top predators give them space because orcas hunt in coordinated groups and adapt fast to new prey.

What makes them so avoided is their flexibility. One pod may specialize in fish, another targets marine mammals, and some have learned techniques like wave washing seals from ice or shore. That behavioral variety is exactly why prey cannot rely on a single defense. Orcas are recognized as apex predators with sophisticated cooperative hunting, according to NOAA Fisheries.

2. Great white sharks turn calm water into exits.

A great white does not need to strike to change the whole mood of a habitat. Along South Africa’s seal islands, California’s central coast, and parts of southern Australia, the classic pattern is sudden silence, fewer surface breaks, and prey hugging safer zones. Seals shift travel routes, and fish tighten into nervous, compact schools. The shark’s size is part of it, but the real pressure is uncertainty, because the approach is often unseen until the last moment.

They are built for surprise. Countershading helps them blend from above and below, and their burst speed can close the final distance quickly. Even when a shark misses, the message lands. Predators that rely on ambush create avoidance that lasts longer than the attack itself. Great whites are widely documented as apex predators with ambush tactics near seal colonies, as reported by National Geographic.

3. Tiger sharks make sea turtles change schedules.

Tiger sharks are the kind of predator that makes prey reorganize their day. In places like Hawaii’s coastal waters, the Bahamas, and Australia’s reef fringes, sea turtles and dugongs often reduce time in open seagrass when tiger sharks are active. The effect is visible in behavior, longer pauses, more cautious surfacing, and a preference for areas with better escape routes.

Their reputation comes from being both powerful and opportunistic. Tiger sharks eat a wide range of prey, which means they do not have to wait for one perfect target to appear. That flexibility keeps the risk constant for everything nearby. They also handle shallow water well, which removes what would otherwise be a refuge. Tiger sharks are described as large generalist predators with broad diets, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History.

4. Sperm whales hunt in darkness with patience.

Sperm whales look slow at the surface, then disappear into a different world. They dive deep, often into the twilight and midnight zones, where they target large squid and fish that rarely see daylight. In regions like the Gulf of Mexico, the Azores, and the waters off New Zealand, sperm whales can reshape deep prey behavior by forcing animals to stay deeper, move differently, or cluster in less optimal layers.

Avoidance here is not about seeing a predator coming, it is about sensing it. Echolocation clicks carry through water like a searchlight, and prey that can detect it may freeze or drop deeper, which costs energy and changes feeding efficiency. The whale’s endurance matters too. A predator that can stay down, scan, and return repeatedly creates a long pressure window. Deep ocean prey live under that pressure most nights.

5. Leopard seals patrol the ice like gatekeepers.

In Antarctic waters, leopard seals are a sharp reason penguins hesitate at the waterline. They often wait near ice edges and breathing holes, using the white and broken texture of ice to hide their shape. When leopard seals are active, penguin groups bunch tighter and time their entries, trying to reduce the odds of one bird being isolated.

Their hunting style is a mix of speed and control. They can grab a penguin or a young seal, then use a shaking technique to tear prey apart. That ability to subdue animals in confined ice edge zones makes them especially feared. They also hunt fish and krill, which keeps them present even when larger prey is scarce. In an environment where safe routes are limited, a predator that controls chokepoints changes everything about movement.

6. Saltwater crocodiles turn estuaries into danger zones.

Some ocean fear starts in brackish water. Saltwater crocodiles live in tidal rivers, mangroves, and coastal lagoons across northern Australia and parts of Southeast Asia, and they can move between river systems and open coast. That mobility makes shoreline animals and even large mammals cautious around crossings, especially at dawn and dusk when crocs are most active.

They are built for stillness and sudden force. A crocodile can hold position with minimal movement, then launch with a burst that leaves little reaction time. Fish and birds respond too, often avoiding narrow channels or shifting feeding spots. Because crocs can survive long periods without eating, they do not need to chase often, which makes them harder to predict. In many coastal communities, the rule is simple, if the water is calm and dark, assume a crocodile is already there.

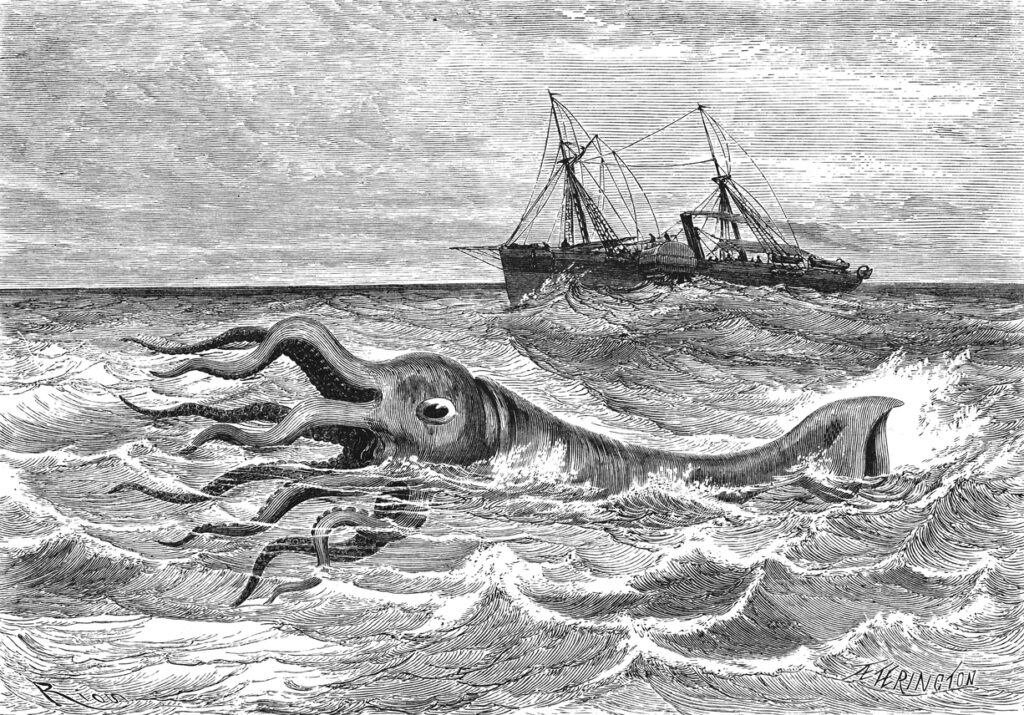

7. Giant squid keep deep prey on edge.

Giant squid are elusive, but their role as aggressive deep predators shows up in scars on sperm whales and in the anatomy built for grabbing. In cold and temperate deep waters, they use long tentacles with powerful suckers to seize prey, and their large eyes are tuned for the faintest light. For animals living in the deep, a predator that can reach out from the dark adds a constant layer of risk.

Avoidance in the deep often looks like vertical migration changes. Prey may shift to different depths to reduce encounters, even if it means worse feeding. A predator does not need to be common to be influential, it only needs to be deadly enough that survival favors caution. Giant squid also remind us that the deep sea has its own apex contests, and many of them happen where humans never see the movement, only the evidence left behind.

8. Giant Pacific octopuses rule small reef corners.

In the kelp forests and rocky reefs of the North Pacific, from British Columbia to Alaska and down toward northern California, a giant Pacific octopus can dominate a patch of seafloor. It hunts crabs, clams, snails, and fish, and it does it with a mix of stealth and strength that makes escape difficult. Prey animals often avoid dens, crevices, and rubble fields that look perfect until a hidden arm reaches out.

This octopus is not fast in the open, it is efficient in close quarters. Its arms can explore holes, lift rocks, and pull prey into a grip that is hard to break. The beak ends the story quickly. Because octopuses learn and adjust, prey cannot rely on one trick. In a reef neighborhood, repeated encounters create a map of fear, and the octopus is often the reason some micro habitats stay oddly quiet.

9. Barracudas make reefs feel suddenly unsafe.

Barracudas are the kind of predator that changes the behavior of small fish just by hovering. On tropical reefs in the Caribbean, the Red Sea, and the Indo Pacific, they often linger near drop offs and reef edges, watching. Their posture looks calm, but the acceleration is not. When a barracuda commits, it can strike fast enough that prey have almost no time to scatter.

They rely on timing and confusion. Small fish respond by tightening their schools, staying closer to cover, and reducing risky foraging in open water. The barracuda’s long body and forward facing teeth are not subtle, and prey seem to treat that silhouette as a warning sign. Even divers notice it, because the fish holds eye contact in a way that feels deliberate. On reefs, predators that patrol edges can control where food is eaten and where it is not.

10. Humboldt squid can turn night water chaotic.

Humboldt squid, also called jumbo squid, operate like a moving threat in the eastern Pacific, especially off Mexico, Peru, and parts of California in certain years. They hunt in groups, and their coordination can make the water feel crowded with predators all at once. Fish respond by changing depth and speed, and even larger animals adjust their routes when squid numbers surge.

What makes them avoided is intensity. They are fast, strong, and willing to attack prey that looks large relative to their body size. They also shift between deep day zones and shallower night hunting, which means prey face risk on a schedule. In seasons when Humboldt squid expand their range, local ecosystems can feel different, not because one predator arrived, but because thousands did. That is a rare kind of pressure, and it forces everything nearby to adapt quickly or get caught.