A handful of dust is raising big questions.

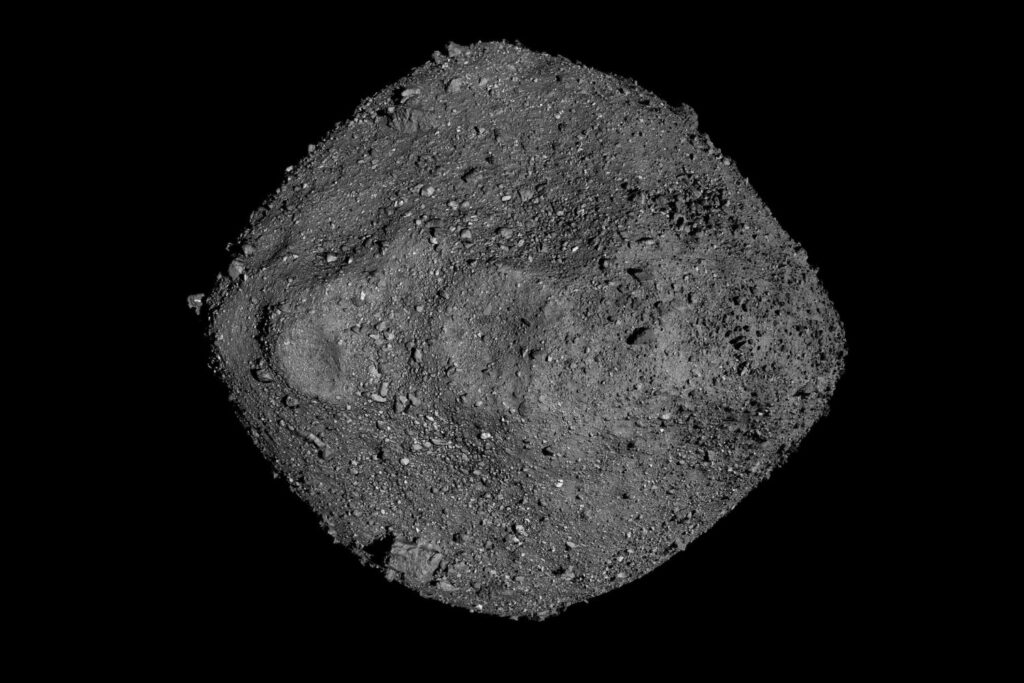

When NASA brought pieces of asteroid Bennu back to Earth, the goal was simple and audacious, touch a relic from the early solar system and read its chemistry like a time capsule. In labs in Houston and around the world, the sample is now revealing carbon rich material, signs of water altered minerals, and a growing list of molecules tied to biology. None of this proves life came from space, but it sharpens the case that key ingredients arrived early and often.

1. Bennu carries carbon that chemistry loves.

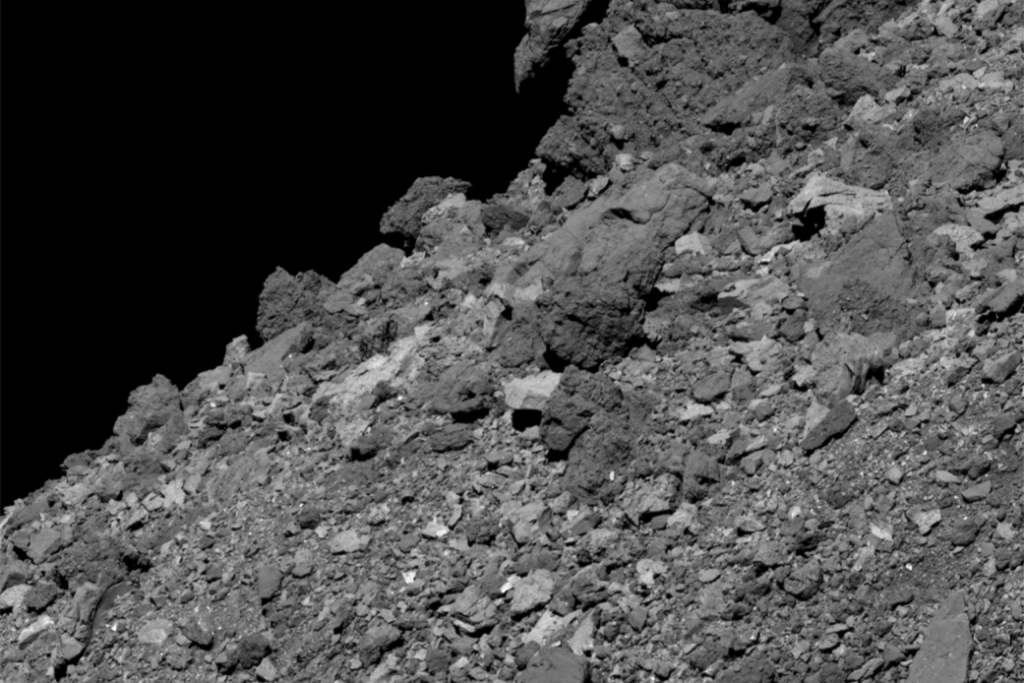

The first shock is how much useful carbon shows up in a small amount of black dust. Carbon is not one thing, it can be simple, stubborn, or surprisingly reactive, and Bennu appears to hold a mix that matters for prebiotic chemistry. In the early solar system, carbon rich asteroids were everywhere, colliding with young planets while surfaces were still volatile and oceans were forming. If those impacts delivered carbon along with water bearing minerals, they may have stocked early Earth with raw material that biology later shaped.

The sample also matters because it is cleaner than most meteorites, which pick up contamination after landing on Earth. In other words, Bennu lets researchers ask what space delivered before weather and microbes got involved. Early lab work highlighted carbon and water signatures in the returned material, according to NASA.

2. Ancient salty water hints at hidden chemistry.

A second layer of the story is that Bennu is not just dry rubble. Mineral clues suggest it formed from a parent body that once hosted liquid water, not as an ocean you could swim in, but as briny fluids moving through rock. When water circulates, it creates micro environments where molecules can concentrate, react, and evolve into more complex forms. That is the kind of setting origin of life researchers care about, because chemistry changes when it is not diluted into nothing.

What raises eyebrows is the salt record itself. Evaporating brines can leave behind phosphate rich minerals, carbonates, and other salts that preserve evidence of a water chemistry past. Those salts also point to ingredients that biology uses heavily, including phosphorus chemistry that is often a bottleneck on young worlds. Bennu salts were identified in returned samples, as reported by Nature.

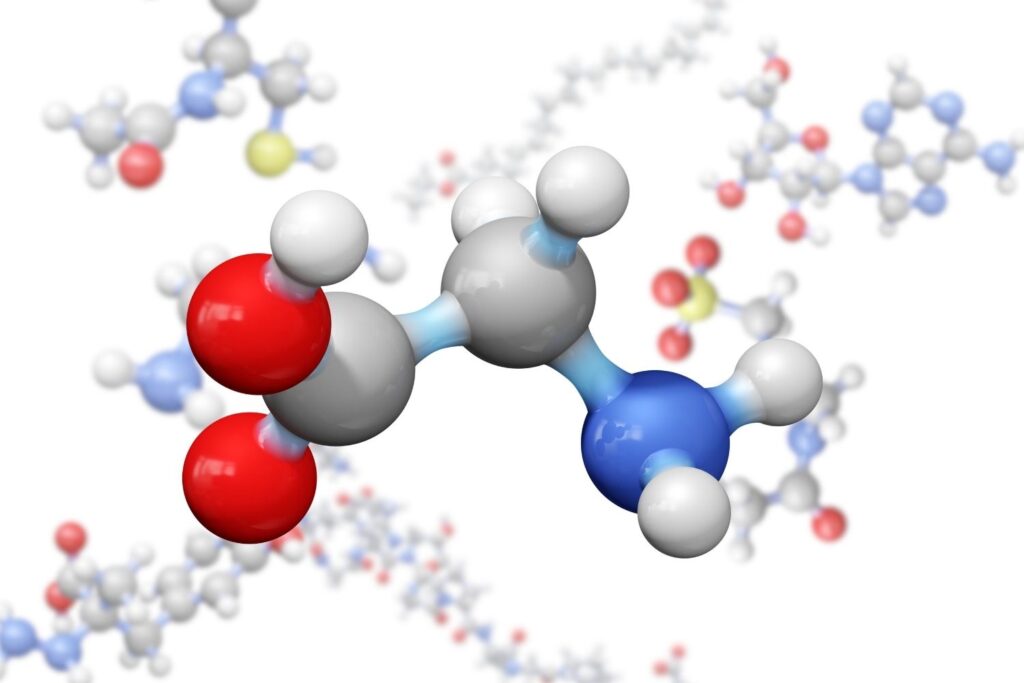

3. Amino acids show up without life attached.

Amino acids are not life, but they are the kind of parts life uses, like loose screws and beams that could become a house. Finding them in a pristine asteroid sample matters because it strengthens the argument that important building blocks form in space and survive the trip to a planet. It also complicates an easy story. On Earth, biology overwhelmingly prefers one handed form of many amino acids, but Bennu results point to mixtures that suggest early chemistry may have started unbiased, then got steered later by environment or chance.

The deeper implication is that Earth may not have needed to invent every ingredient locally. It could have received a starter kit repeatedly through impacts, dust, and debris over millions of years. That makes life feel less like a single lucky lightning strike and more like a long process with many deliveries. Laboratory analyses report a range of amino acids in Bennu material, according to PNAS.

4. Water altered minerals change the whole timeline.

When you see clay minerals and water altered rock in a sample like Bennu, it forces a different picture of the early solar system. Instead of dry stones drifting in cold space, you have parent bodies that warmed up, melted internal ice, and ran water through cracks and pores. That kind of geologic activity can happen surprisingly early, driven by heat from short lived radioactive elements. It also means chemistry had time to simmer before asteroids ever broke apart and scattered.

For Earth, that matters because it suggests some prebiotic processing happened before impact delivery. The planet may have received not just raw ingredients but ingredients already altered by water chemistry, which can make certain reactions easier. In a sense, the asteroid becomes a lab that ran long before Earth cooled enough for stable seas, handing over products that Earth later reused in its own experiments.

5. Impact delivery works best during messy early eras.

The moment when Bennu like material would matter most is when Earth was young, hot, and constantly hit. Early impacts were violent, yet they were also frequent opportunities to add water, organics, and reactive minerals. Some incoming material burns up, but not all. Larger fragments can reach the surface, and smaller dust can rain down over time, spreading ingredients broadly rather than dumping them in one crater.

This helps explain why origin of life theories often focus on accumulation, not single events. Life needs concentration and repetition. If asteroid debris delivered organics again and again, then lakes, tidal flats, and volcanic pools could have been replenished even after sterilizing events. Bennu does not prove this happened, but it makes the delivery scenario more chemically plausible because the materials are not imaginary, they are measurable in a modern sample.

6. Phosphorus becomes less mysterious in brines.

One of the quiet problems in origin of life research is phosphorus availability. Biology needs it for genetic material, cell membranes, and energy transfer, yet many common phosphorus minerals are not easily dissolved in water. Briny systems can change that. Salts, pH shifts, and evaporation can mobilize phosphorus in ways that make it more chemically active, and Bennu type salts point to that kind of environment.

If early Earth received phosphate bearing minerals from carbon rich bodies, that could have boosted the odds of forming key compounds without requiring rare local geology. It also widens the search beyond Earth. Any world with water, rock, and intermittent brines could have similar chemical opportunities. Bennu is a reminder that small bodies can host complex geochemistry, and the most important chemistry may happen in cramped spaces where fluids concentrate and then dry down again.

7. Contamination concerns shrink with sealed samples.

Meteorites have taught scientists a lot, but they come with a constant question, what got added after landing. Soil microbes, rainwater, lab handling, and even storage conditions can alter organics. Bennu samples were collected in space and curated under strict protocols, which makes them far more trustworthy for delicate molecules. That is why the results feel heavier than another meteorite headline.

This matters because origin of life debates often hinge on small differences. If a molecule is rare or easily destroyed, you need confidence that it is truly extraterrestrial. Sample return missions create that confidence. They also allow repeated testing across different labs, using different methods, which reduces the chance that one measurement error becomes a grand conclusion. Bennu is not only a source of molecules, it is a cleaner courtroom for deciding what space chemistry actually produces.

8. The sample suggests many worlds got similar deliveries.

Bennu is a near Earth asteroid today, but its material likely connects to a larger family of carbon rich bodies that circulated throughout the early solar system. If Bennu carries organics, salts, and water altered minerals, it is reasonable to imagine that many similar bodies did too. That means early Earth may not have been uniquely gifted. It may have been one of many rocky worlds receiving steady inputs of chemistry from space.

This expands the emotional stakes. It makes the origin of life feel less like a miracle reserved for one planet and more like a probability game shaped by environment and time. The ingredients may be common, while the final assembly depends on local conditions, stability, and perhaps sheer persistence. Bennu becomes a proxy for a broader population, hinting that the early solar system was not chemically barren, it was chemically busy.

9. Chemistry alone still needs a workable setting.

Even with a rich inventory, ingredients do not automatically become life. They need cycles, concentration, and energy gradients. That means Bennu like deliveries are only half the story. The other half is where on Earth those materials landed and what happened next. Tidal flats can concentrate solutions. Hydrothermal systems provide energy and mineral surfaces. Wet dry cycles can drive reactions that water alone will not.

This is where the narrative stays tense. Bennu strengthens the idea that Earth had access to important molecules, but it also raises the bar for explaining how those molecules became organized. The most realistic pathway is not a straight line. It is repeated attempts, with chemistry failing often and succeeding rarely, until a self sustaining system emerged. Bennu may have supplied fuel, but Earth still had to build the engine.

10. Bennu makes life’s origin feel less isolated.

The most lasting shift is psychological. When scientists open a sample and find multiple classes of molecules tied to biology, along with minerals shaped by water, it nudges the story away from isolation. Earth looks less like a lone stage and more like part of a network of exchanging materials. Asteroids, comets, dust, and impacts become part of the planet’s early supply chain.

That does not reduce Earth’s role, it sharpens it. The planet still needed the right conditions to take advantage of what arrived. But Bennu suggests those arrivals were chemically meaningful, not random rocks. If similar deliveries happened on Mars, on icy moons, or on young exoplanets, the question shifts from can life start at all to where it had enough time and stability to keep going.