Ancient stones are forcing historians to look again.

Across Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Mesopotamia, archaeologists continue uncovering inscriptions, seals, and administrative records that intersect with biblical narratives in ways that are difficult to dismiss. These finds do not verify theology or miracles, but they complicate claims that major biblical figures were invented long after the fact. Names appear in enemy records, tax lists, victory monuments, and imperial correspondence. Each discovery increases tension between minimalist readings of the Bible and the physical record beneath the soil. Archaeology rarely settles debates cleanly, but it keeps reopening them.

1. King David appears in an unexpected enemy inscription.

For much of the twentieth century, King David was treated by some scholars as a legendary founder created to legitimize later rulers. That assumption shifted when fragments of a basalt victory monument were discovered at Tel Dan, erected by an Aramean king celebrating military success over Israel.

According to the Israel Antiquities Authority, the inscription references the House of David, indicating a recognized royal dynasty named after a founder. The fact that the reference appears in a hostile source strengthens its credibility. While debates over translation persist, the inscription strongly suggests David was remembered as a historical ruler within living cultural memory, not a distant myth.

2. King Hezekiah left physical traces of preparation.

Biblical accounts describe Hezekiah ordering major defensive measures before an Assyrian invasion, including securing Jerusalem’s water supply. Archaeological excavations revealed a massive tunnel carved through solid limestone, channeling water into the city while denying it to attackers.

As reported by National Geographic, an inscription inside the tunnel records its construction process, including the moment two teams met in the rock. The engineering sophistication and urgency align closely with siege conditions. Beyond confirming Hezekiah’s existence, the tunnel demonstrates centralized authority, labor coordination, and technical knowledge consistent with a historical monarch responding to real geopolitical threats.

3. Pontius Pilate appears in a Roman dedication.

Pontius Pilate was once known only through biblical and later Roman texts, leaving some room for skepticism. That changed when a limestone block was uncovered at Caesarea Maritima during excavations of a Roman theater.

As stated by the Israel Museum, the inscription identifies Pilate as prefect of Judea, confirming both his name and official title. This find anchors gospel narratives within a documented Roman administrative framework. It demonstrates that New Testament events unfolded under real imperial governance, reducing arguments that Pilate was a literary invention rather than a historical official overseeing a volatile province.

4. King Omri reshaped the regional power balance.

Although the Bible devotes relatively little attention to Omri, Assyrian records treat him as a major political figure. Foreign inscriptions repeatedly refer to Israel as the land of Omri long after his death, indicating lasting influence.

Archaeological remains at Samaria show large scale construction and urban planning during his reign. These findings suggest Omri established a stable and influential dynasty that shaped Israel’s political identity. The contrast between biblical emphasis and archaeological prominence highlights how scripture reflects theological priorities rather than historical importance alone.

5. Ahab appears in enemy military records.

Ahab is often portrayed negatively in biblical texts, yet Assyrian inscriptions present him as a formidable military ally. Records from the Battle of Qarqar list Ahab contributing a large contingent of chariots to a regional coalition resisting Assyria.

This external account indicates significant military resources and political standing. It challenges simplified portrayals by showing Ahab as an active participant in international power struggles. Archaeology thus reframes him not merely as a flawed king, but as a ruler operating within a complex geopolitical landscape.

6. Nebuchadnezzar dominates both text and ruins.

Nebuchadnezzar II appears extensively in Babylonian inscriptions, building records, and royal proclamations. Excavations in Babylon reveal monumental walls, temples, and palaces bearing his name.

These physical remains align with biblical descriptions of a powerful king responsible for Jerusalem’s destruction and exile. The consistency between archaeological evidence and textual accounts strengthens confidence that biblical authors were responding to real historical trauma inflicted by a well documented imperial ruler.

7. Cyrus the Great left a policy record.

The Cyrus Cylinder records imperial policies of repatriation and religious tolerance following Babylon’s conquest. These policies closely parallel biblical descriptions of Cyrus allowing exiled communities to return and rebuild.

The artifact demonstrates that such actions were not unique favors, but part of broader imperial strategy. Cyrus emerges as a historically consistent ruler whose documented governance aligns with biblical memory, reinforcing the text’s grounding in known political practices rather than later invention.

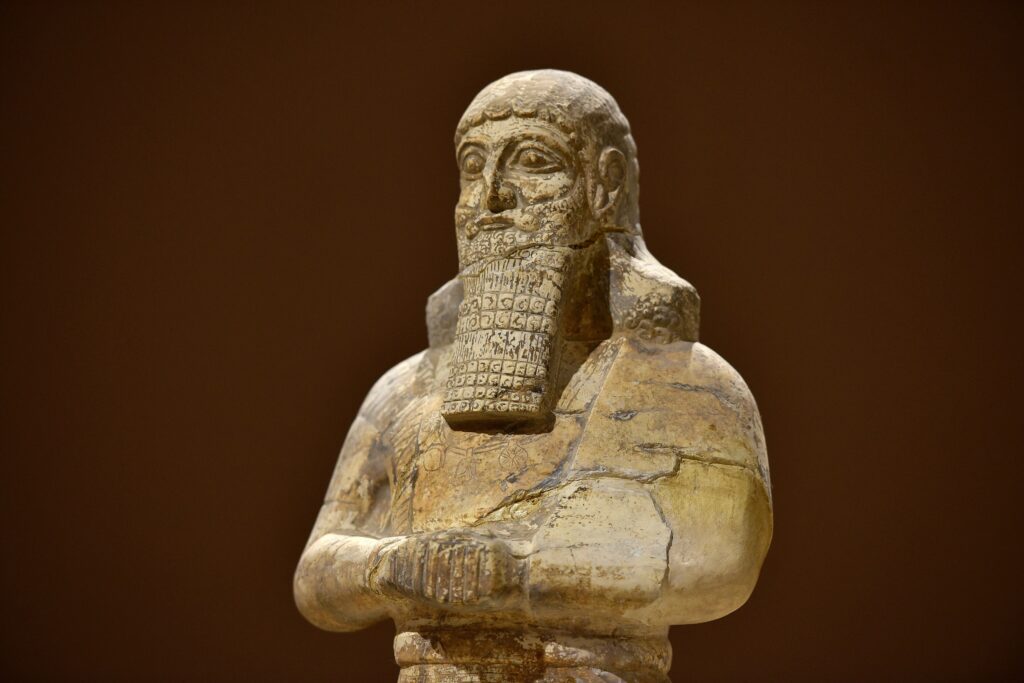

8. Shalmaneser III recorded Israelite kings.

Assyrian reliefs and inscriptions from Shalmaneser III document interactions with Israelite rulers, including tribute payments and military encounters. These records provide external confirmation of Israel’s participation in regional power networks.

They show Israel functioning as a recognized polity rather than an isolated or exaggerated entity. Archaeology thus situates biblical kingdoms within the same diplomatic systems described in Mesopotamian archives, strengthening their historical plausibility.

9. Jehoiachin appears in ration tablets.

Babylonian administrative tablets list food rations allocated to Jehoiachin, identified as king of Judah, and his family. These mundane records carry exceptional historical weight.

They confirm Jehoiachin’s captivity and royal status in exile, matching biblical descriptions. The tablets also reveal how displaced kings were integrated into imperial bureaucracy, providing rare insight into the lived consequences of conquest described in scripture.

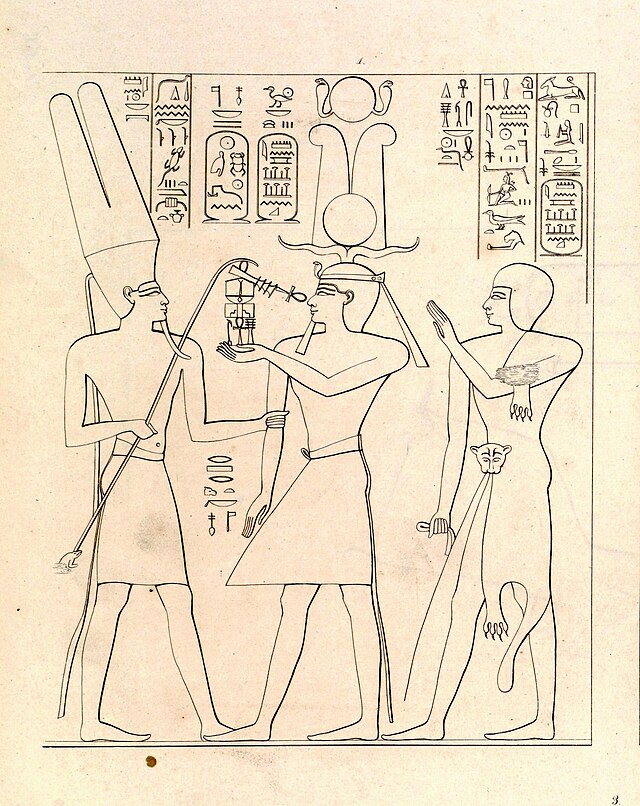

10. Pharaoh Shoshenq entered Israelite territory.

Egyptian inscriptions at Karnak describe a military campaign into the Levant by Pharaoh Shoshenq I. Biblical texts describe a similar invasion during the reign of Rehoboam.

Archaeological destruction layers in several cities align with the timing of this campaign. The convergence of Egyptian and biblical sources suggests shared historical memory of regional upheaval rather than isolated storytelling.

11. Balaam appears in unexpected prophetic texts.

An inscription discovered at Deir Alla references Balaam son of Beor, portraying him as a renowned seer receiving divine visions. This text is independent of Israelite tradition.

Its existence indicates Balaam was known across cultural boundaries. The find suggests biblical authors incorporated figures already circulating in regional memory, rather than inventing characters solely for narrative purposes.

12. Sargon II was once doubted entirely.

Sargon II was long dismissed as fictional due to lack of evidence, despite biblical references. That skepticism collapsed when inscriptions and palaces bearing his name were uncovered at Khorsabad.

This reversal serves as a cautionary example. Archaeology demonstrates how absence of evidence can reflect incomplete excavation rather than nonexistence. Sargon’s rediscovery underscores why debates over biblical figures remain open as long as the ground continues to yield new data.