Each excavation layer raises a more troubling question.

In southeastern Turkey, archaeologists excavating a windswept limestone ridge keep encountering evidence that does not fit older narratives. The site sits in Şanlıurfa Province, within the Taş Tepeler region of Upper Mesopotamia, and dates to the Pre Pottery Neolithic, roughly 9600 to 8200 BCE. What began as scattered monumental stones has revealed something more complex. Large circular spaces, carved human heads, and statues point toward organized gatherings long before farming villages took hold. Each season sharpens the tension between what was expected and what the stones insist on showing.

1. Göbekli Tepe revealed unexpected scale and ambition.

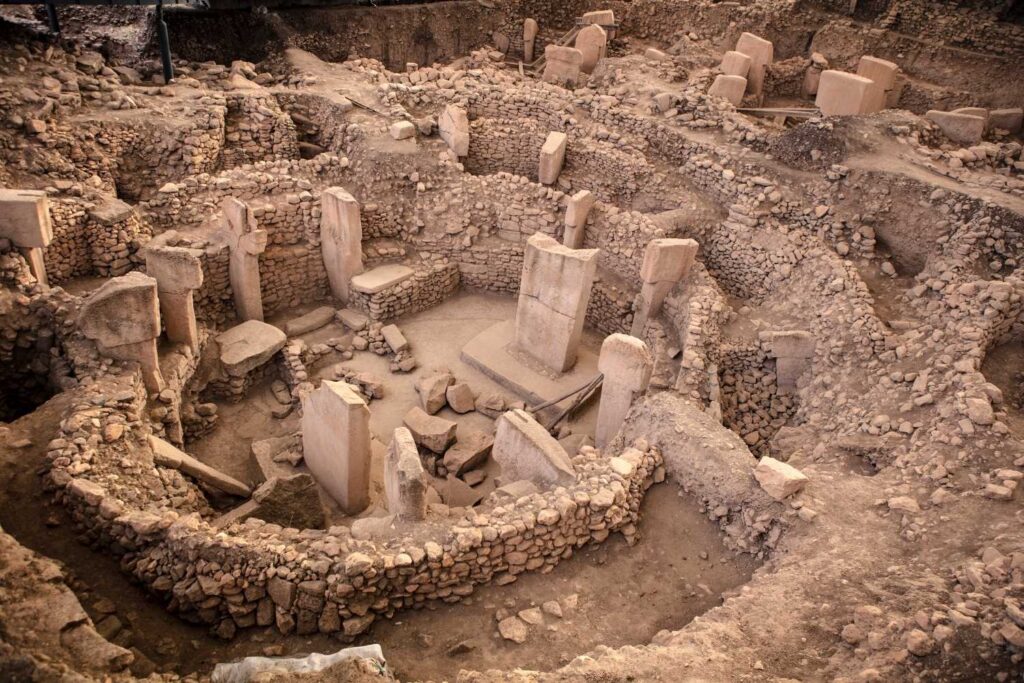

As excavation deepened at Göbekli Tepe, the first surprise was not what appeared, but how much of it kept appearing. Circular stone enclosures emerged one after another, each defined by towering T shaped limestone pillars that dwarfed anything associated with daily life from the same era. The scale alone suggested sustained effort, not a brief experiment. These were not isolated monuments. They were part of something larger, layered, and unfinished in ways that hinted at long use.

According to the German Archaeological Institute, radiocarbon dates place major construction phases around 9600 to 9000 BCE. Building at this scale, this early, required coordination that should not have existed yet, intensifying questions about who organized it and why.

2. Karahantepe expanded the pattern beyond a single site.

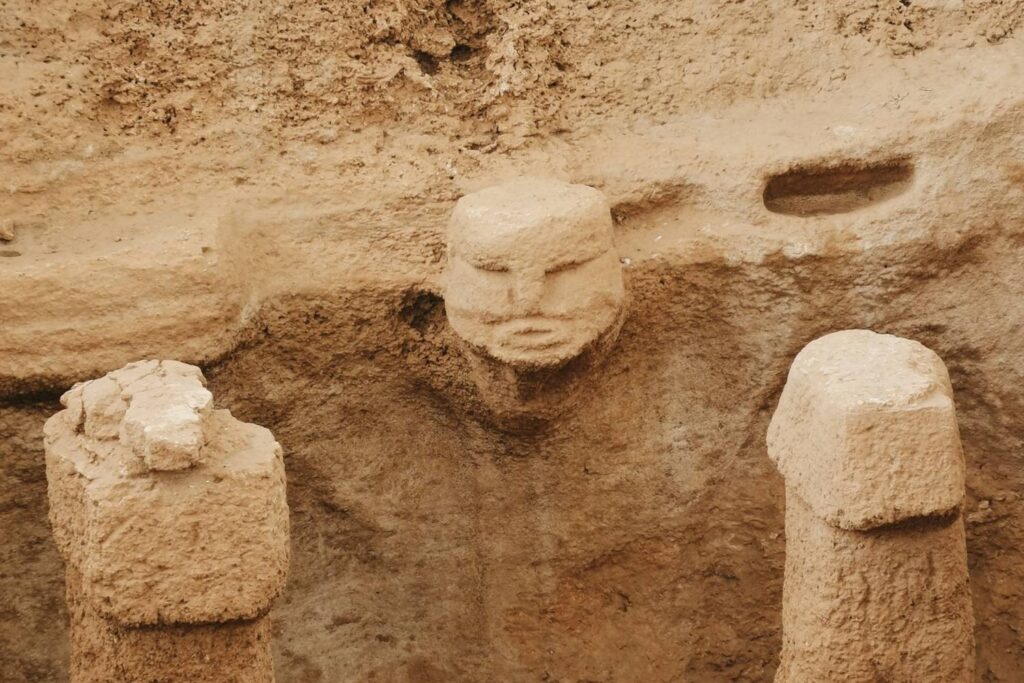

The discovery of Karahantepe, located roughly thirty five kilometers east of Göbekli Tepe, complicated interpretations further. Here, archaeologists uncovered similar monumental elements alongside carved human heads emerging directly from bedrock. This was no isolated anomaly.

As reported by Science, the repetition of sculptural forms across sites suggests a regional tradition rather than a one off experiment. The findings indicate shared symbolic practices across Upper Mesopotamia, pointing to widespread communal behaviors earlier than expected.

3. Amphitheater like spaces resisted domestic explanations.

Several structures at both sites form circular, open areas with inward facing stone elements. These spaces lack hearths, storage pits, or household debris typical of living quarters. Their design invites gathering rather than shelter.

As stated by researchers in Antiquity, the architectural layout supports interpretation as communal or ritual spaces. The absence of domestic features strengthens the case that these were venues for group activity, not residences, reshaping views of early Neolithic social life.

4. Carved human heads appeared deliberately positioned.

Human heads carved in stone recur across excavation layers. Some are freestanding, others embedded within walls or emerging from architectural elements. Their placement appears intentional rather than decorative.

The repetition and positioning suggest symbolic roles tied to memory, identity, or ritual. These carvings imply shared meanings understood by participants, pointing toward belief systems sophisticated enough to persist across generations.

5. Dating places construction before full agriculture.

Radiocarbon analysis consistently places major construction phases before widespread farming. This timing unsettles models linking monument building to agricultural surplus.

Sustaining such projects without farming implies alternative food strategies and social incentives. The evidence suggests that communal gathering itself may have driven cooperation, rather than surplus production alone.

6. Rebuilding shows long term site importance.

Excavation layers reveal repeated rebuilding and modification of structures. Enclosures were repaired, altered, and reused rather than abandoned.

This persistence indicates enduring significance. Communities returned over centuries, maintaining traditions and spaces that anchored collective identity across time.

7. Animal imagery added symbolic complexity.

Alongside human forms, reliefs depict animals including snakes, foxes, and birds. These figures are integrated into architectural contexts rather than isolated art.

The imagery suggests symbolic narratives linking humans and animals. Such integration points toward cosmological thinking embedded within communal spaces.

8. Site placement favored symbolism over resources.

Both Göbekli Tepe and Karahantepe sit away from prime water sources or arable land. Their locations appear chosen for visibility or meaning rather than subsistence advantage.

This suggests neutral or shared ground where dispersed groups could convene. The choice of place reinforces interpretations of intentional gathering points.

9. Regional timelines now require revision.

Comparable sites across the Taş Tepeler region are being reevaluated in light of these discoveries. What once seemed isolated now appears connected.

If similar structures existed elsewhere, early social complexity was more widespread than assumed. The timeline for organized communal life must shift accordingly.

10. Each season continues to disrupt certainty.

Ongoing excavation keeps adding detail without closing debate. New sculptures and spaces complicate earlier interpretations rather than confirming them.

The sites resist simple classification. They force archaeologists to confront the possibility that large scale communal life emerged earlier, and for reasons more complex, than traditional models allowed.