Its size hints at a busy world history barely recorded.

A large wooden vessel has emerged from northern European waters, and it does not fit quietly into the record. Its size, construction, and location suggest it was built for more than local travel, hinting at heavy cargo, long routes, and a level of planning that complicates what historians assumed about the period. The wreck sits where ships were not expected to concentrate, raising questions about how crowded these waters once were. Taken together, the clues point to a web of movement and exchange far denser than medieval maps imply, one that relied on ships whose sophistication is only now coming into view.

1. The shipwreck was identified as the royal flagship Gribshunden.

The vessel emerging from Baltic waters was not anonymous cargo debris. Archaeologists identified it as Gribshunden, the flagship of King Hans of Denmark and Norway, a ship tied directly to royal power and diplomacy. Its scale and weaponry immediately separated it from local merchant craft expected in the region.

Gribshunden sank in 1495 while carrying the king’s entourage toward Kalmar. Its role as a floating court and military platform reframes the wreck as a centerpiece of late medieval statecraft rather than an isolated maritime accident.

2. Its location challenges assumptions about medieval shipping routes.

The wreck rests off the coast of Ronneby, Sweden, near the island of Stora Ekön, an area not previously considered a major medieval shipping hub. This placement unsettled long held ideas about where large vessels operated during the fifteenth century.

Finding a royal flagship here suggests denser traffic across the southern Baltic than historical maps indicate. Political travel, military movement, and commercial exchange likely intersected these waters more frequently, reshaping views of Northern Europe as a connected maritime network rather than scattered coastal corridors.

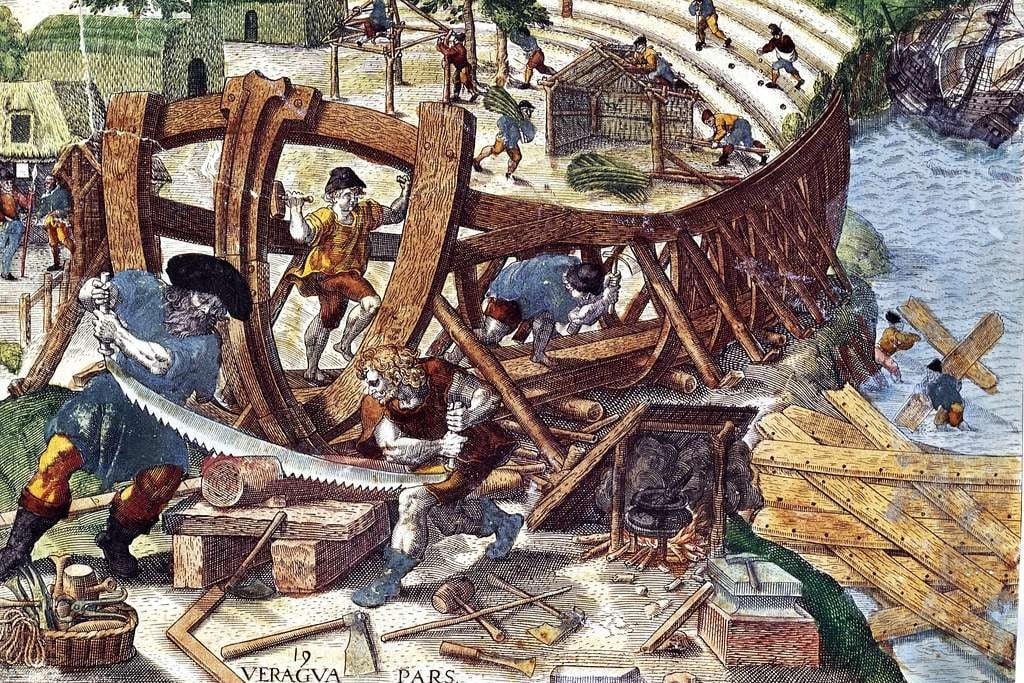

3. Construction techniques reveal unexpected shipbuilding sophistication.

Gribshunden measures over thirty five meters long, rivaling ships thought to appear decades later. Its hull blends clinker and early carvel construction, signaling advanced design experimentation earlier than historians once accepted.

This hybrid structure allowed greater size, stability, and cargo capacity while supporting heavy armament. The ship’s build suggests Northern European shipyards were innovating rapidly, responding to political ambition and expanding naval warfare. Gribshunden becomes evidence that technological evolution at sea accelerated faster than surviving written records suggest.

4. Preserved weaponry confirms its role as a warship.

Bronze cannons recovered from the wreck are among the earliest ship mounted artillery found in the region. Their placement indicates Gribshunden was designed for direct naval confrontation, not merely defense against pirates.

Alongside crossbows, armor, and ammunition, the weapons point to a vessel prepared for force projection. This challenges portrayals of late medieval fleets as lightly armed. Instead, Gribshunden demonstrates that naval warfare had already become central to royal power before the sixteenth century arms race traditionally marks that transition.

5. The cargo reflects elite travel rather than routine trade.

Archaeologists recovered luxury items including imported spices, fine tableware, and personal goods linked to royal attendants. These finds distinguish the ship from commercial freighters carrying bulk commodities.

Such cargo confirms Gribshunden functioned as a mobile seat of authority. Kings traveled with material symbols of power, diplomacy, and ceremony. The ship’s interior was likely arranged to host negotiations and project legitimacy, revealing how political presence at sea mirrored court life on land.

6. The sinking disrupted a critical diplomatic mission.

Gribshunden was en route to Kalmar as King Hans sought to secure alliances within the Kalmar Union. Its loss was not merely material but political, destabilizing negotiations underway across Scandinavia.

The sinking underscores how fragile medieval diplomacy could be when tied to maritime travel. One accident altered power dynamics between Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The wreck therefore records a moment where ocean conditions directly influenced European political outcomes.

7. Shallow burial preserved rare organic materials.

The wreck lies at approximately ten meters depth, where cold, low oxygen Baltic waters slowed decay. This environment preserved wooden structures, food remains, and ship fittings rarely found intact.

Such preservation allows archaeologists to reconstruct daily life aboard a royal vessel. From diet to storage practices, Gribshunden offers insight into how crews lived during extended voyages. These details transform the wreck from a structural artifact into a human record of medieval seafaring.

8. Its discovery reshaped timelines of naval armament.

The presence of advanced artillery aboard Gribshunden pushes naval militarization earlier than many models allow. Ship mounted cannons were once thought uncommon before the sixteenth century.

This evidence forces historians to reconsider how quickly gunpowder changed maritime strategy. Northern European powers were experimenting with floating firepower sooner, suggesting naval dominance emerged incrementally rather than suddenly. Gribshunden becomes a marker of that transitional phase.

9. The wreck reveals crowded waters long overlooked.

Multiple ships from similar periods have since been identified nearby, indicating Ronneby’s waters supported sustained maritime activity. Gribshunden was not alone in these routes.

This clustering implies shared corridors for trade, war, and diplomacy intersected here. The Baltic emerges as a contested, busy space rather than a peripheral sea. Gribshunden helps redraw medieval maritime geography with greater density and complexity.

10. Its legacy alters how medieval power is understood.

Gribshunden shows that royal authority traveled by sea with infrastructure, weaponry, and ceremony intact. Power was mobile, not confined to castles or capitals.

The ship demonstrates how governance, warfare, and commerce fused aboard single vessels. Its rediscovery forces a reevaluation of medieval states as maritime actors earlier than assumed. Gribshunden is not an anomaly but a surviving witness to a world whose scale historians are only beginning to recognize.