Ancient genomes rewrite early medieval Britain’s story.

A recent genetic study of seventh century burials in southern England revealed that two individuals, one in Kent and another in Dorset, had a grandparent from West Africa. The results challenge long held assumptions about the genetic uniformity of Anglo Saxon England and point to a far more interconnected past than once believed. These burials were typical in every way, which makes their ancestry all the more remarkable.

Their remains were found among ordinary graves, buried with items that showed no signs of foreign origin. This suggests these individuals were fully accepted members of their communities, not outsiders.

1. Ancient DNA showed 20 to 40 percent West African ancestry.

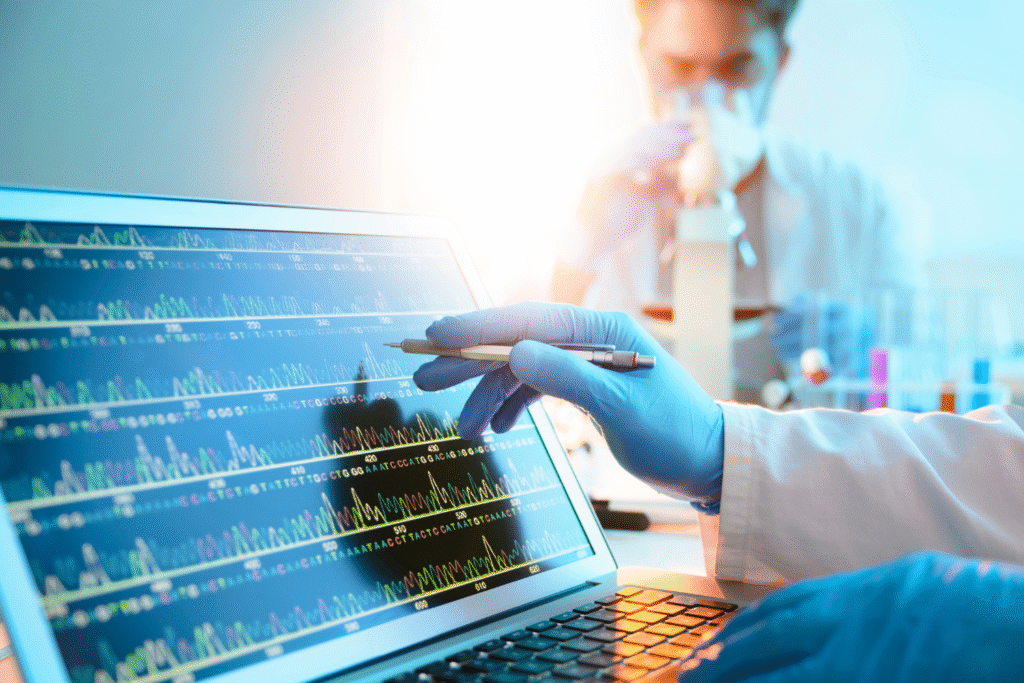

When scientists sequenced the DNA from the remains, they found unmistakable traces of sub Saharan ancestry. Researchers determined that roughly 20 to 40 percent of each individual’s genome came from West African sources, with the remainder matching Northern European populations. The findings are detailed in recent publications in Antiquity.

This proportion points to a relatively close ancestor, possibly a grandparent, rather than distant admixture. It provides direct evidence of genetic diversity in early medieval England that scholars had long considered unlikely.

2. Maternal lines remained European despite mixed ancestry.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis revealed that both individuals carried maternal lineages typical of northern Europe. This indicates that their mothers were likely local or regional women. Their African ancestry must therefore have entered through paternal lines, possibly from men who traveled long distances, as stated by the researchers who conducted the study.

That pattern matches scenarios where men from afar arrived through trade or migration and integrated into existing local populations. It also shows that population blending was not a one way process but part of wider human movement across continents.

3. The burials followed standard local customs and styles.

Archaeologists examining the graves noted that they contained typical Anglo Saxon items, such as pottery, buckles, and a spoon similar to others in nearby tombs. The individuals were buried according to the customs of their time without any indication that their ancestry set them apart, as discovered by the authors of the research.

This conformity shows that ancestry did not determine social status or burial treatment. They lived and died within the same cultural framework as their neighbors, reflecting a shared local identity despite diverse origins.

4. The sites lie in Kent and Dorset, far apart geographically.

One set of remains was uncovered at Updown in Kent, while the other was found in Worth Matravers in Dorset. These regions are more than 200 miles apart, suggesting the phenomenon was not isolated to a single community. Each site had independent cultural histories, yet both contained individuals of mixed heritage.

Kent served as a major continental gateway, while Dorset was a quieter coastal region. Finding similar ancestry in both demonstrates how widespread movement and contact must have been across early medieval Britain.

5. Their African roots align with Yoruba and Mende groups.

Genetic comparisons linked the sub Saharan component of their DNA to modern West African populations, including the Yoruba, Mende, and Esan peoples. That connection gives researchers a clearer picture of where the African ancestry likely originated. It is the first genetic evidence tying England to these regions during the early Middle Ages.

Although ancient migration routes remain uncertain, the precision of the match suggests genuine historical contact, whether through trade, service, or movement across the Mediterranean and beyond.

6. Trading routes or travel likely explain their presence.

Historians point to the vast network of trade routes that stretched from North Africa into Europe and eventually to the British Isles. Some travelers may have come directly from African coastal regions, while others might have moved through Mediterranean or continental European settlements before reaching England.

The graves themselves contained continental items such as Frankish ceramics, underscoring how goods and people alike crossed immense distances. Such mobility reveals a level of global connection far earlier than many previously assumed.

7. These are among the first confirmed cases in England.

Until recently, genetic studies of Anglo Saxon populations showed little to no sub Saharan ancestry. This discovery marks one of the earliest confirmed examples of African genetic presence in early medieval England. It provides physical evidence for what had only been theoretical.

By expanding the known genetic diversity of the era, these findings reshape how historians and scientists view early English communities. The past was more mixed, and more connected, than the written record suggests.

8. The individuals appear fully integrated into local society.

Nothing in their burial patterns suggests that these individuals were treated as foreigners. They were laid to rest among their peers, with the same modest items and attention to custom. This equality in death implies equality in life.

Such treatment indicates that cultural belonging, rather than ancestry, defined identity. Early English communities may have valued participation and kinship above appearance or origin.

9. The discovery alters understanding of medieval connectivity.

These genetic results force a reconsideration of how isolated early England truly was. The data supports a picture of movement that included not only traders and sailors but families who settled, married, and raised children far from their ancestral homes.

Migration has always shaped human history, but evidence like this turns abstract speculation into tangible proof. It shows that even in a time of limited technology, people and cultures reached farther than we once imagined.

10. More surprises may be waiting in other burials.

Researchers plan to reexamine remains from other Anglo Saxon cemeteries using updated DNA methods. If more examples of mixed ancestry appear, they could transform how we understand the composition of medieval Britain entirely.

Future work may reveal that early England was not a closed island society but a living crossroads of global connections. These two graves remind us that history often hides its most remarkable truths in the smallest fragments of bone and DNA.