Light and shadow are rewriting the past.

For generations, spirals and abstract figures etched into canyon walls across the American Southwest were cataloged as symbolic art. They were photographed, sketched, and admired, but rarely tested against the sky. Now researchers returning to sites in and around Chaco Canyon are watching sunlight move across those carvings with instruments and software rather than intuition. As solstices arrive and shadows shift, some panels appear less decorative and more deliberate, raising questions about what their makers were tracking in stone.

1. Solstice light strikes specific carved spirals.

At sites near Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon, narrow beams of sunlight cut across carved spirals during solstices. Observers have documented how shadow and light interact precisely with petroglyph panels on specific days each year. According to National Park Service documentation on Chaco Culture National Historical Park, the Sun Dagger site famously aligns with solstice and equinox light patterns.

This recurring illumination is not random. Researchers argue that repeated, predictable solar interaction suggests intentional placement. The carvings appear positioned to mark seasonal turning points rather than simply decorate canyon walls.

2. The Sun Dagger drew early scientific scrutiny.

In the 1970s, artist Anna Sofaer documented light passing through rock slabs at Fajada Butte, illuminating spiral carvings at solar standstills. Her findings attracted both enthusiasm and skepticism within archaeology.

As reported by Smithsonian Magazine, subsequent studies examined whether the alignment was deliberate or coincidental. Although access to the site is now restricted to prevent damage, the documented interactions between sunlight and carved spirals established a framework for testing astronomical hypotheses rather than relying on visual impression alone.

3. Researchers now test alignments with digital tools.

Earlier claims about archaeoastronomy often relied on field observation. Today, scholars combine drone photogrammetry, 3D scanning, and solar modeling software to test whether alignments hold mathematically.

Recent studies published in Journal of Archaeological Science Reports have modeled how solstice light interacts with petroglyph panels across different centuries. As stated by researchers affiliated with University of Colorado Boulder, these methods reduce subjectivity by simulating solar paths and shadow movement. The results suggest some panels were positioned with knowledge of long term solar cycles rather than chance placement.

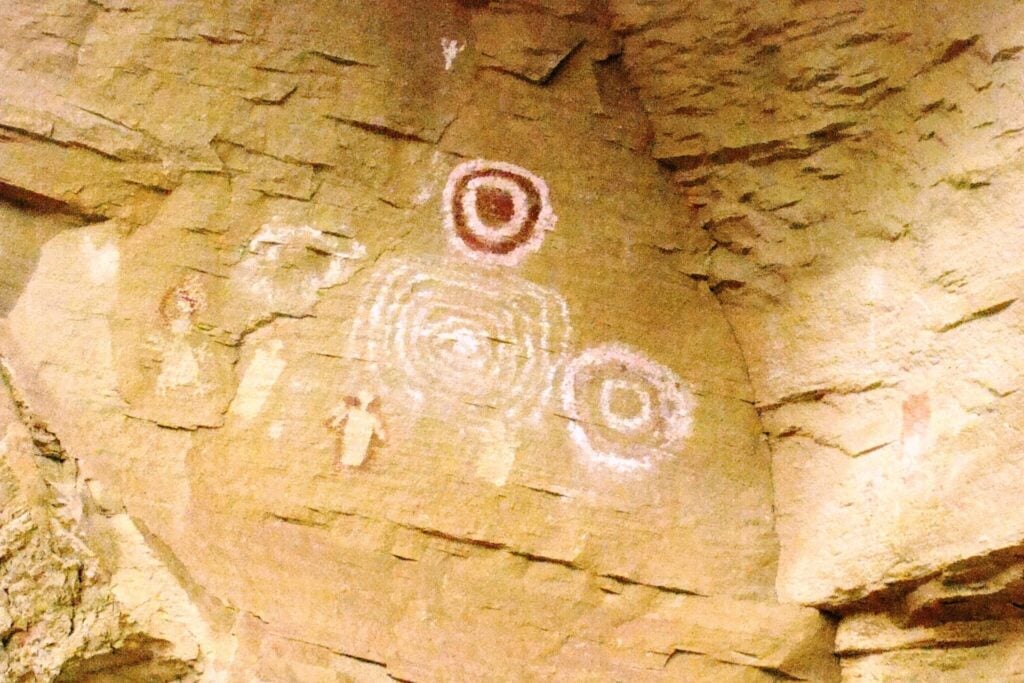

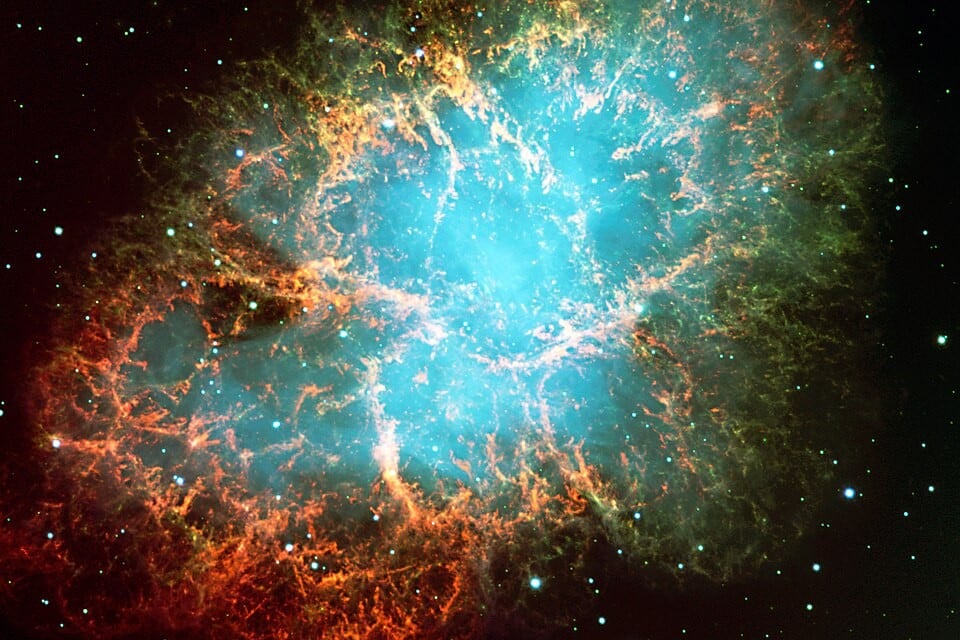

4. Some panels may record the 1054 supernova.

Among the carvings studied in the Southwest are glyphs interpreted by some scholars as depicting the supernova of 1054, which was recorded in Chinese astronomical texts and produced the Crab Nebula.

Petroglyphs in New Mexico show a star like symbol beside a crescent moon, positioned in a way that could correspond to the sky configuration observed in July 1054. While debate continues, the possibility that such events were documented in stone expands the scope of what these carvings may represent.

5. Chaco Canyon served as a ritual hub.

Between roughly 850 and 1150 A.D., Chaco Canyon in present day New Mexico functioned as a major ceremonial center for Ancestral Puebloan communities. Great houses such as Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl were aligned along cardinal directions.

Architectural orientation toward solar and lunar standstills reinforces the idea that astronomical observation was integrated into ritual life. Petroglyph panels surrounding the canyon may have complemented built structures, creating a landscape calibrated to celestial cycles.

6. Lunar standstills appear in carved clusters.

Beyond solar events, researchers have examined whether certain panels align with the 18.6 year lunar standstill cycle. This rare astronomical event alters the moon’s maximum rise and set positions.

Some glyph clusters correspond with extreme lunar positions when modeled against reconstructed horizons. These potential alignments suggest observational traditions extended beyond annual solar tracking into multi decade cycles requiring long term record keeping.

7. Light and shadow create moving markers.

Unlike static art, these carvings interact dynamically with sunlight. Shadows cast by overhanging rocks or adjacent slabs move across spiral grooves during specific times of year.

This motion transforms carved stone into a functional calendar device. The interaction depends on precise angles and seasonal timing, reinforcing arguments that placement was intentional. The carvings respond to the sky, turning canyon walls into instruments rather than passive surfaces.

8. Skepticism remains within archaeology.

Not all scholars accept archaeoastronomical interpretations. Critics caution against confirmation bias, warning that large numbers of carvings increase the chance of coincidental alignments.

Recent digital modeling addresses these concerns by testing whether alignments exceed statistical expectation. The debate continues, but the conversation has shifted from speculation to measurable geometry and astronomical simulation.

9. Regional studies extend beyond Chaco.

Petroglyph panels across Arizona, Utah, and Colorado are being reexamined using similar analytical tools. Sites such as Hovenweep and Mesa Verde contain carvings that may interact with seasonal light.

Comparative studies seek patterns across the broader Southwest rather than isolated examples. If consistent alignments appear across multiple regions, the case strengthens for a shared astronomical tradition embedded within rock art.

10. Technology is reshaping interpretation.

High resolution scanning allows researchers to measure carving depth, orientation, and erosion patterns with precision. Solar path software reconstructs sky positions for centuries in the past.

These tools help determine whether alignments would have functioned when the carvings were made. By combining archaeology with astronomy and digital modeling, scholars move beyond visual intuition toward reproducible analysis.

11. The canyon walls now read differently.

As evidence accumulates, panels once cataloged as decorative motifs appear increasingly tied to cycles of light and celestial motion. What looked abstract gains seasonal rhythm under scrutiny.

The shift does not erase artistic meaning, but it adds functional dimension. In and around Chaco Canyon, stone surfaces may represent a fusion of symbolism and observation, where carved spirals captured the turning of the sun across generations.