A long-lost gospel attempts to flip betrayal into speculation.

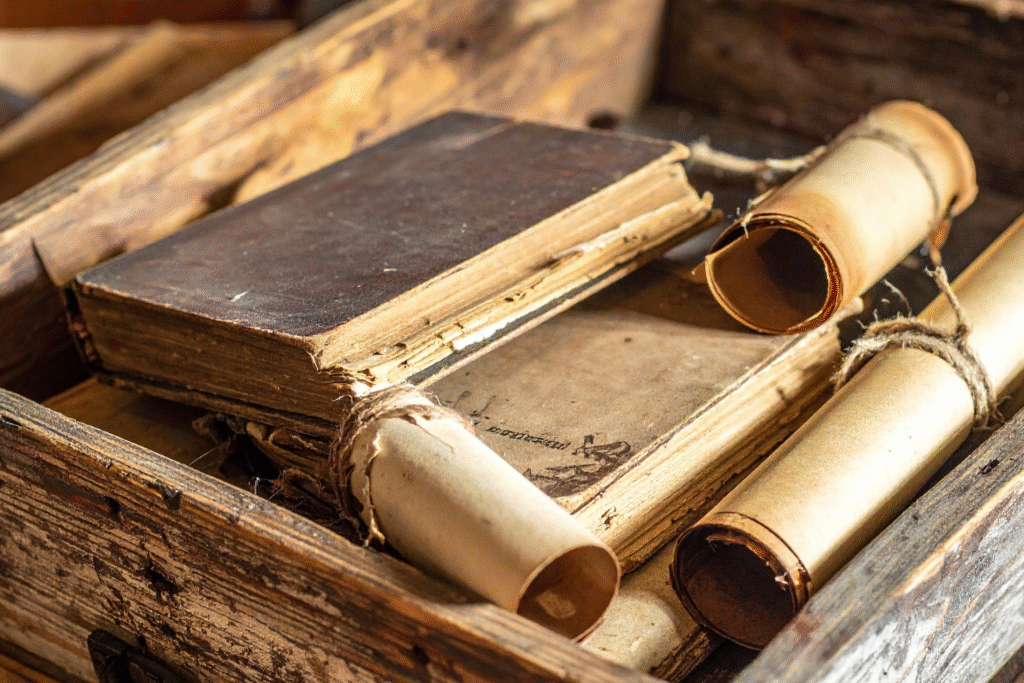

When a brittle stack of papyrus pages was pulled from the Egyptian desert, it appeared to speak in the voice of Judas Iscariot himself. Known as the Gospel of Judas and dated to around 300 A.D., the text challenges the traditional account of Jesus’ betrayal. But scholars emphasize that while the manuscript is authentic to its era, it is not part of the Bible and does not represent historical truth. Instead, it reveals how alternative beliefs, known as Gnosticism, once vied for attention before being rejected by early Christian leaders.

1. The discovery happened in the Egyptian desert near El Minya.

The manuscript was unearthed near El Minya, Egypt, in the 1970s, sealed in a limestone box and later sold on the black market. Scholars eventually realized the text’s significance when they identified its ancient Coptic script describing Judas and Jesus in dialogue. The details of its recovery were documented in a 2006 investigation, according to National Geographic. While historically fascinating, researchers clarify that it is a product of a fringe sect’s theology, not a missing biblical book. Its value lies in what it shows about early Christian diversity, not divine revelation.

2. The gospel portrays Judas as a trusted confidant, not a villain.

Unlike the biblical version, this text portrays Judas as Jesus’ chosen confidant—someone who understood his divine purpose more deeply than the other disciples. Scholars working with the codex found a passage where Jesus tells Judas to “sacrifice the man that clothes me,” implying a spiritual mission rather than treachery, as stated by PBS News. But theologians caution that this interpretation reflects Gnostic symbolism, not fact. It represents a belief system that diverged sharply from mainstream Christianity and was later denounced as heresy.

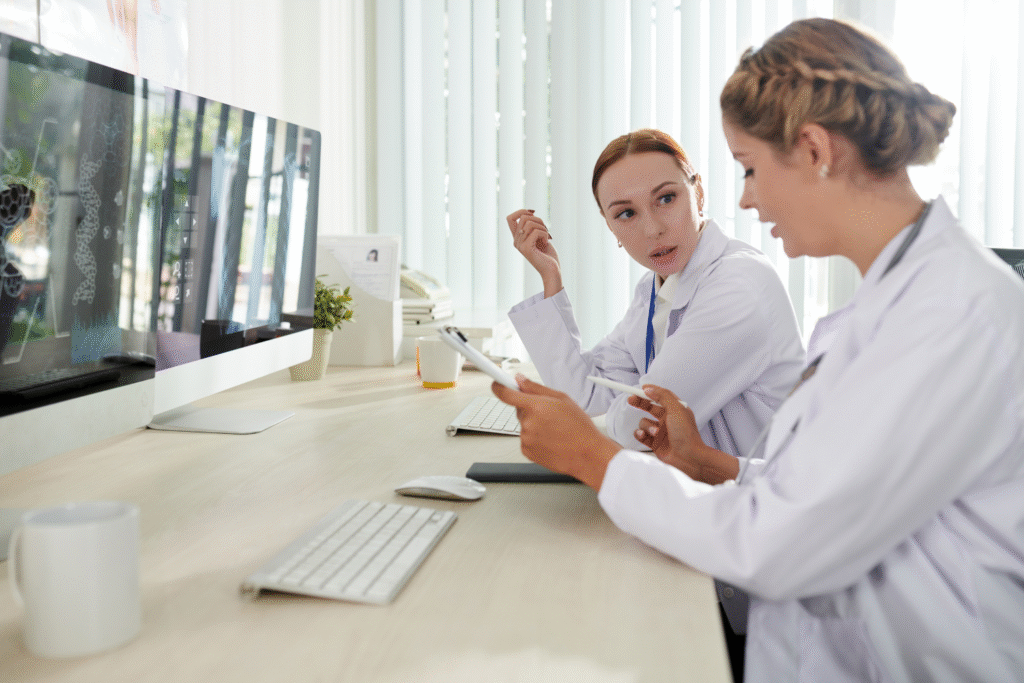

3. Radiocarbon dating confirmed the text’s ancient origins, not its truth.

Researchers at the University of Arizona’s AMS laboratory dated the papyrus and binding to between 220 and 340 A.D., confirming the text’s physical age, as reported by the Tucson Citizen. However, authenticity of material does not equal accuracy of message. Scholars note that while the document is historically genuine, it offers insight into one group’s mystical interpretation, not evidence that Judas acted differently than recorded in the canonical gospels. The distinction between artifact and authority remains central to understanding its significance.

4. The manuscript spent decades hidden in a safety deposit box.

After its discovery, the codex passed through private hands, eventually ending up in a New York bank vault where it deteriorated for nearly two decades. When conservators finally examined it, the manuscript had broken into hundreds of fragile fragments. Its survival owes more to modern restoration than divine preservation. Though its content intrigued the public, historians remind readers that the Church’s decision to exclude it from scripture was deliberate—its theology conflicted with the established understanding of Christ’s teachings.

5. It reveals a version of Jesus rooted in Gnostic cosmology.

In the text, Jesus speaks of invisible realms, cosmic rulers, and a world created by lesser gods. This language is characteristic of Gnostic writings, which taught that enlightenment came from secret knowledge rather than faith or grace. The gospel’s portrayal of Judas as enlightened fits that pattern. While intellectually captivating, this view belongs to a mystical philosophy rejected by early Church fathers for contradicting the belief in a single, sovereign Creator. It’s a glimpse into what some early Christians thought, not what the faith ever accepted as truth.

6. Scholars say it exposes the diversity of early Christian thought.

Before the canon was finalized, dozens of sects claimed access to Jesus’ real message. The Gospel of Judas shows that early Christianity was far from uniform—some saw salvation through knowledge, others through sacrifice. Yet over time, Church councils determined which writings aligned with apostolic teaching. Texts like this were excluded not for lack of intrigue, but for theological inconsistency. The discovery doesn’t rewrite scripture; it simply reminds us that religious ideas were contested long before they were codified.

7. The translation reignited debate but not doctrine.

When the Gospel of Judas was published in 2006, it drew global attention. Some hailed it as a window into forgotten theology, while others called it a distortion of Christian belief. The Vatican quickly clarified that it does not alter the Church’s understanding of Judas or Jesus. For scholars, its value lies in its context—an ancient attempt to reimagine faith through a Gnostic lens, not a revelation that overturns two thousand years of scripture.

8. Restoration efforts saved the codex from near disintegration.

By the time conservators intervened, the papyrus was a patchwork of brittle fragments. Restoration teams in Switzerland painstakingly reassembled it, preserving a rare glimpse into how alternate Christian texts were recorded. Their work ensured that historians could study the document without confusing its survival with sacred authority. The gospel’s fragility mirrors the fate of Gnosticism itself—an idea that nearly vanished, sustained today only by curiosity and cautionary interest.

9. The story of Judas remains one of interpretation, not revision.

The Gospel of Judas invites reflection but not reinterpretation of scripture. It offers a speculative vision where Judas serves a divine purpose, but this stands outside Christian doctrine. The canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John remain the foundation of accepted Christian teaching, while this text endures as an artifact of belief gone another way. Its rediscovery doesn’t change faith’s history—it simply illuminates how many paths once branched from the same story before the Church drew its defining line.