Genetic clues reveal ancient connections once considered impossible.

Archaeologists long assumed Arctic societies were shaped mostly by isolation, constrained by ice, distance, and extreme seasons. Artifacts hinted otherwise, but evidence remained circumstantial. Recent genetic analysis of ancient human remains has changed that balance. DNA recovered from burial sites across northern Alaska now raises the stakes, suggesting repeated contact across thousands of miles. These findings force researchers to reconsider how people moved, traded, and maintained relationships in environments once thought to limit long distance exchange.

1. Genetic markers link Point Hope to Pacific Coast peoples.

Burial mounds near Point Hope on Alaska’s northwest coast have long hinted at distant connections, but new genetic evidence sharpens the mystery. Human remains from the site carry mitochondrial DNA lineages uncommon in Arctic populations and more closely associated with ancestral Pacific Northwest coastal groups, suggesting people, not just objects, traveled surprising distances.

Radiocarbon dating places the individuals between 900 and 1,300 years ago. Research reported by Science found these genetic markers align with coastal populations farther south, pointing to repeated contact over generations rather than a single migration event. Paired with nonlocal burial goods, the DNA strengthens evidence of sustained long distance trade networks linking Arctic and Pacific coast societies.

2. Inland Arctic burials carry unexpected coastal ancestry signals.

DNA extracted from remains near the Kobuk River, more than one hundred miles inland from the Bering Sea, reveals ancestry typically associated with Pacific coastal communities. These individuals lived far from marine environments previously assumed to limit interaction.

The findings complicate long held views of regional separation. As stated by researchers writing in Nature, the genetic mixing likely reflects seasonal movement or exchange networks rather than permanent relocation of entire populations.

3. Genetic evidence mirrors known artifact trade routes.

Archaeological sites in northern Alaska have yielded obsidian traced to the Wrangell Mountains and marine shells sourced from the Pacific coast. DNA evidence now mirrors these material exchanges, strengthening interpretations of human mobility.

The overlap between genetic data and artifact distribution suggests people moved alongside goods. According to a report by Smithsonian Magazine, the combined evidence indicates trade networks that extended across ecological zones and cultural boundaries.

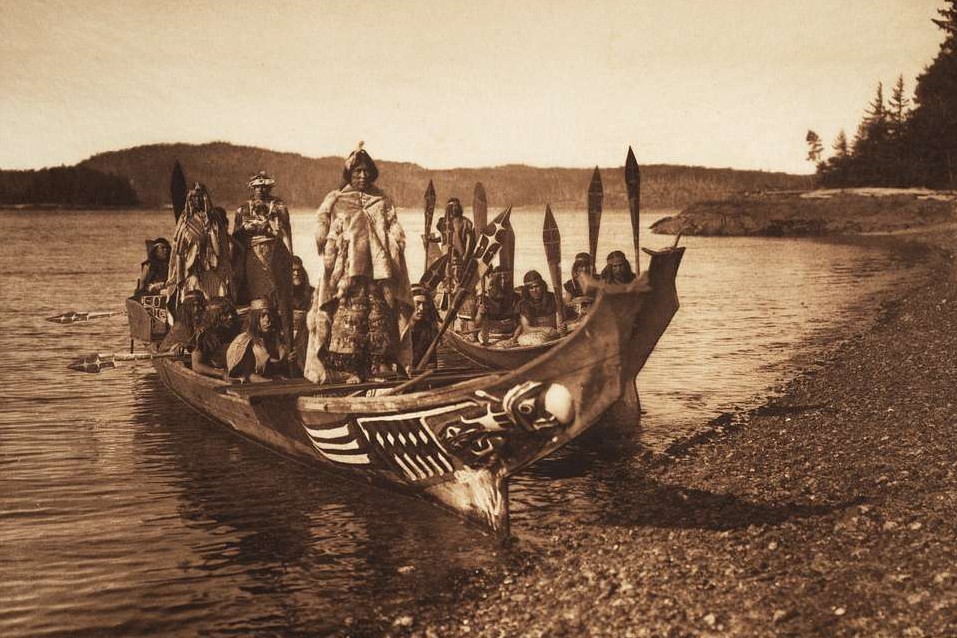

4. Coastal travel routes connected Alaska to British Columbia.

The most plausible exchange pathways followed coastlines from southern Alaska through the Alexander Archipelago into present day British Columbia. These routes offered predictable access to marine resources and seasonal shelter.

Travel along these corridors required advanced knowledge of tides, currents, and weather. Such repeated movement implies organized exchange systems capable of functioning despite extreme conditions and shifting ice patterns.

5. Marriage alliances likely reinforced long distance trade relationships.

Sustained genetic mixing over centuries suggests more than occasional encounters. Intermarriage between distant groups would explain how specific DNA lineages persisted across generations.

Marriage alliances strengthened trust, facilitated resource sharing, and anchored trade networks socially. These relationships transformed long journeys into predictable connections maintained through kinship rather than constant travel alone.

6. Seasonal mobility shaped Arctic social organization.

Seasonal movement appears central to how Arctic communities organized daily life and survival. Evidence suggests groups shifted between coastal camps in summer and inland settlements during winter, allowing access to marine mammals, caribou, fish, and traded goods while avoiding seasonal scarcity and danger.

This flexibility contradicts older models of permanent villages. Mobility supported trade timing, social gatherings, and marriage exchanges, embedding long distance connections into routine movement. Rather than wandering, travel followed predictable schedules shaped by environment, memory, and inherited knowledge passed across generations. Such rhythms reduced risk and reinforced trust among distant partners across northern coastlines and river systems.

7. Environmental mastery enabled repeated long distance journeys.

Repeated long distance journeys required more than physical endurance. Travelers needed intimate knowledge of sea ice behavior, currents, storms, and animal migration timing to avoid lethal mistakes across exposed coastlines and frozen passages.

This expertise suggests knowledge transmission systems as complex as the trade itself. Navigation skills were likely taught through storytelling, apprenticeship, and repeated practice. Mastery of environmental signals turned dangerous terrain into reliable corridors, enabling exchange to persist despite climate shifts, ice variability, and generational change. Without such precision, even short journeys could become fatal for entire families moving between seasonal camps over many centuries of Arctic history.

8. Genetic links blur Arctic and Pacific cultural boundaries.

Genetic overlap challenges the idea that Arctic and Pacific peoples developed separately. Shared lineages indicate sustained interaction that shaped identity, kinship, and cultural practice over centuries rather than brief or accidental contact.

These findings suggest boundaries drawn by modern maps did not constrain ancient relationships. Coastal and Arctic groups likely viewed each other as part of connected worlds linked by travel, exchange, and ancestry. Cultural differences existed, but they evolved alongside contact rather than in isolation. DNA now captures those relationships where artifacts alone could not, forcing scholars to reconsider long standing cultural assumptions about northern human history and interaction.

9. Isolation models fail to explain Arctic development.

Older archaeological models portrayed Arctic societies as isolated adaptations to harsh environments. The genetic data disrupts that narrative, suggesting interaction was not incidental but foundational to survival and resilience.

Exchange networks diversified food sources, technology, and social ties, reducing vulnerability during poor seasons. Contact allowed communities to share tools, raw materials, and environmental knowledge. Isolation would have increased risk, not security, in unpredictable northern climates shaped by ice and scarcity. The evidence reframes Arctic development as collaborative rather than solitary, built through relationships extending far beyond immediate territory and sustained across many generations of movement and shared risk and survival.

10. Ancient trade systems rival later historic networks.

The scale of these ancient exchange systems rivals trade networks often credited to later societies. Goods, people, and genetic material moved reliably across enormous distances without written records or centralized authority.

This discovery challenges timelines of social complexity in northern regions. Arctic and Pacific communities maintained durable networks through trust, knowledge, and repetition. Their success depended on memory, skill, and cooperation rather than infrastructure, revealing sophisticated organization hidden within landscapes long assumed marginal. These findings place northern peoples firmly within global human history as active participants shaping exchange long before modern economies emerged elsewhere on the planet or were recorded.