Archaeological discoveries reveal widespread underground construction across multiple regions.

Recent archaeological investigations have uncovered thousands of underground tunnels scattered across Europe and other continents, some dating back over 5,000 years. These discoveries reveal remarkable patterns of underground construction by ancient civilizations across vast distances and time periods.

The evidence suggests ancient peoples developed sophisticated underground solutions to common challenges facing their communities. Archaeological findings demonstrate humanity’s long-standing relationship with subterranean construction, showing how different cultures created elaborate tunnel systems during times of conflict, extreme weather, or religious persecution.

1. Medieval European tunnels challenge assumptions about Dark Age capabilities.

Dr. Heinrich Kusch documented hundreds of narrow tunnels called “Erdstalls” beneath settlements across Central Europe in his research on underground passages. Bavaria alone contains over 700 documented tunnel systems, while Austria holds hundreds more of these mysterious constructions. However, radiocarbon dating places most of these tunnels between 950-1300 AD, making them medieval rather than prehistoric.

Most Erdstall tunnels measure just 70 centimeters wide and extend no more than 50 meters in length. These cramped passages include small chambers, storage areas, and tight “slip passages” connecting different levels. Their purpose remains unknown, with theories ranging from hiding places during raids to religious or spiritual functions. The lack of artifacts inside these tunnels adds to their mystery.

2. Turkey’s Derinkuyu represents pinnacle of ancient underground engineering.

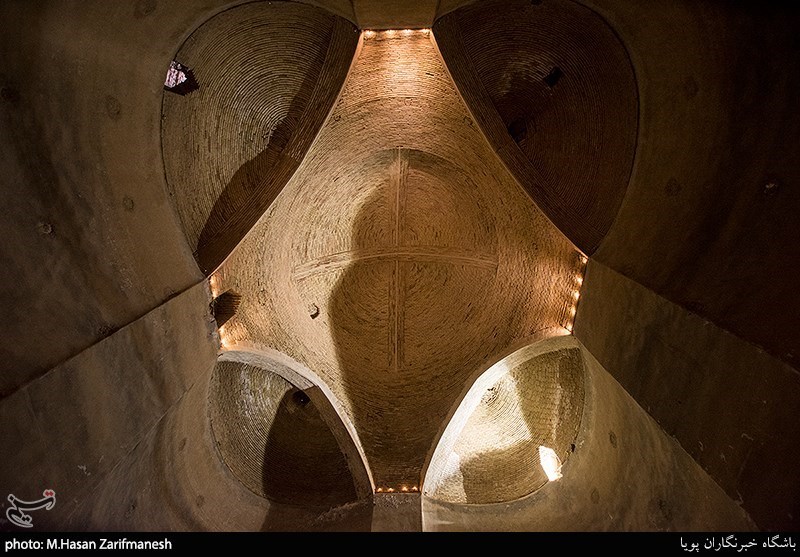

Turkey’s Cappadocia region houses extraordinary underground cities, with Derinkuyu being the largest and most sophisticated. This complex extends 85 meters deep and housed up to 20,000 people along with livestock and supplies, as documented by extensive archaeological surveys. The city features wine cellars, stables, chapels, schools, and even a cruciform church carved into volcanic tuff rock.

Construction likely began with the Hittites around 1200 BCE, though most development occurred during Byzantine times for protection during Arab-Byzantine wars. The accidental 1963 discovery happened when a homeowner knocked down his basement wall during renovations. Rolling stone doors could seal each of the 18 levels independently, while an intricate ventilation system with over 50 shafts maintained air circulation throughout the complex.

3. Soft volcanic rock enabled sophisticated underground construction techniques.

Cappadocia’s unique geology made extensive underground excavation possible using relatively simple tools, according to geological studies of the region’s pyroclastic rock formations. The volcanic tuff remains stable when carved but soft enough to excavate without modern machinery. This geological advantage explains why this region developed the world’s most extensive underground cities.

Similar geological conditions exist in other volcanic regions worldwide, leading to comparable underground developments. Iran’s Nushabad underground city and various cave dwellings across different continents demonstrate how geology influenced human settlement patterns. The technical knowledge required to maintain structural integrity while excavating these spaces suggests sophisticated understanding of engineering principles among ancient builders.

4. Global patterns suggest independent development rather than connected networks.

Archaeological evidence reveals similar underground construction techniques across continents, but these likely represent parallel development rather than cultural exchange. Underground settlements appear in Iran, Armenia, China, and various locations throughout the Americas. Each region developed solutions appropriate to local geology, climate, and threats.

The consistency of certain design elements – ventilation systems, defensive features, storage areas – reflects common human needs rather than shared knowledge. Native American legends describe extensive underground passages, while archaeological evidence supports sophisticated subterranean construction in multiple regions. These similarities demonstrate universal human responses to environmental and security challenges rather than evidence of ancient global communication.

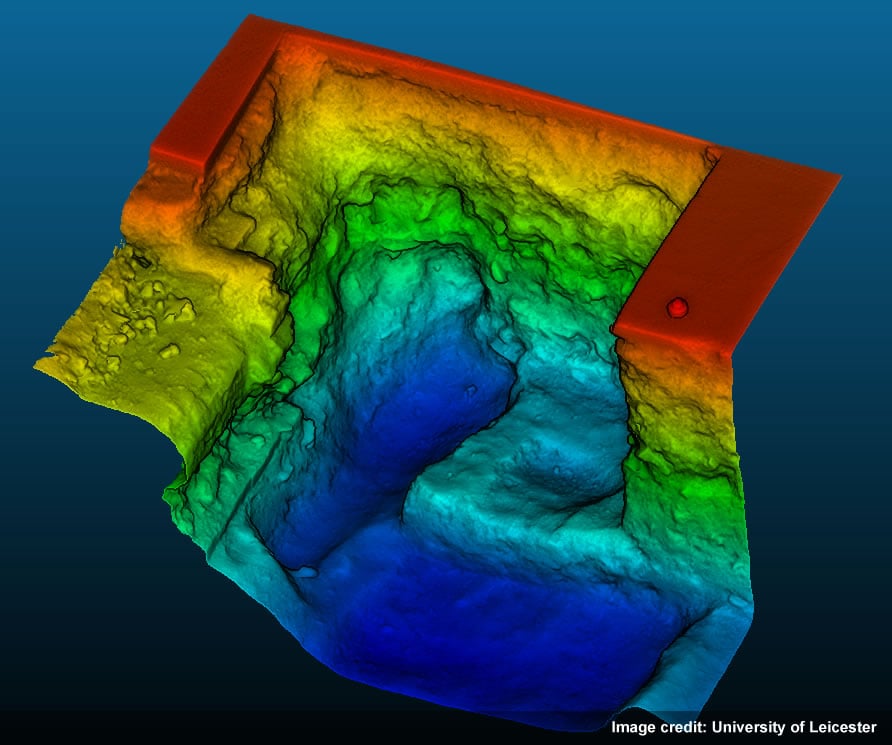

5. Modern scanning reveals extensive medieval tunnel networks previously unknown.

Ground-penetrating radar and LIDAR technology continue discovering previously unknown medieval tunnel systems beneath European towns and archaeological sites. These surveys reveal that underground construction was far more common during the Middle Ages than historical records suggest. Many systems remain unexplored due to safety concerns and preservation requirements.

Recent technological advances allow non-invasive exploration of fragile underground structures. Advanced robotics now map passages too narrow for human access, while 3D scanning creates detailed records of tunnel layouts and construction techniques. Each survey reveals additional complexity in medieval underground infrastructure, suggesting these projects required significant community organization and technical expertise.

6. Religious suppression may explain gaps in historical documentation.

Medieval church records rarely mention underground tunnels, despite archaeological evidence showing many churches were built directly over tunnel entrances. This pattern appears throughout Europe, suggesting possible ecclesiastical efforts to suppress or control access to these structures. The Church may have viewed these passages as connected to pre-Christian religious practices.

Systematic documentation gaps make dating and understanding tunnel purposes challenging for modern researchers. The absence of written records contrasts sharply with the extensive physical evidence, indicating deliberate historical omission rather than lack of knowledge. This suppression may explain why many tunnel systems remained unknown until modern archaeological methods rediscovered them.

7. Conflict and persecution drove repeated underground refuge construction.

Historical analysis reveals underground refuges were actively used during specific periods of conflict and persecution across different regions. Derinkuyu saw heavy use during Arab-Byzantine wars (780-1180 AD) and later during Mongol raids. European Erdstall tunnels coincide with periods of Viking raids and political instability during the early medieval period.

Underground cities provided protection not just from military threats but from religious persecution. Cappadocian Christians used these refuges during Ottoman rule, while similar patterns appear in other regions where minority populations faced systematic oppression. The strategic positioning near water sources and on defensible terrain indicates builders possessed sophisticated understanding of military and survival needs.

8. Archaeological evidence suggests sophisticated medieval engineering previously underestimated.

These underground constructions demonstrate that medieval societies possessed advanced engineering capabilities often overlooked by historians. The precision required for long-term structural stability in soft rock indicates sophisticated understanding of geology and construction principles. Medieval builders successfully created complex ventilation systems, drainage networks, and multi-level layouts without modern tools.

The scale and coordination required for larger projects challenges assumptions about medieval organizational capabilities. Evidence suggests extensive planning, skilled labor specialization, and community coordination far exceeding typical historical portrayals of the “Dark Ages.” These discoveries contribute to growing recognition that medieval technological and organizational achievements were more sophisticated than previously recognized.