A rare amphibian now gets a fragile second chance.

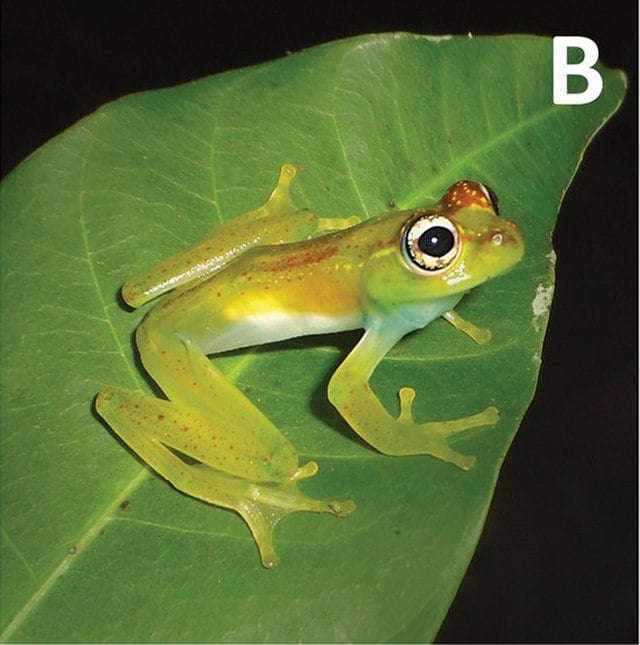

Deep in the humid forests of Madagascar, scientists are racing to save one of the island’s most fragile amphibians—the Ankarafa skeleton frog (Boophis ankarafensis). Once found calling from clear forest streams, it now clings to survival in a single patch of forest on the Sahamalaza Peninsula. Its numbers have dropped so low that biologists warn a single cyclone or outbreak could erase it entirely. In response, emergency breeding centers have begun raising the last remaining frogs under controlled conditions, hoping to secure their future before the rainforest silence becomes permanent.

1. The species survives in only one forest patch.

According to the Bristol Zoological Society’s Madagascar Amphibian Conservation Program, the Ankarafa skeleton frog exists solely within the boundaries of Sahamalaza–Iles Radama National Park. It occupies a few shaded streams within the Ankarafa forest, an area now threatened by illegal logging and slash-and-burn agriculture. This micro-endemic range leaves it defenseless against any environmental shock. Researchers say the species’ survival depends entirely on a forest fragment smaller than most small towns. That isolation is both its signature and its downfall—a rare life form trapped in an ever-shrinking home.

2. Recent surveys found only a handful of frogs.

Field expeditions in 2023 and 2024 recorded alarming declines across sites where the frog was once common. As stated by the IUCN Red List, researchers detected only a few calling males during peak breeding season, signaling near collapse. Some formerly active stream systems are now silent. The frogs’ disappearance is tied to forest clearing that warms the water and eliminates shaded habitat. Scientists say that without rapid intervention, the population will not recover naturally, a grim acknowledgment for a species already pushed to the edge of extinction by human hands.

3. Captive breeding facilities are now operational.

Madagascar’s Ministry of the Environment, in partnership with the Amphibian Survival Alliance and Mongabay-supported researchers, has initiated controlled breeding programs inside biosecure facilities. The centers replicate the frogs’ cool, shaded stream conditions, with regulated humidity and light cycles designed to mimic their home habitat. Staff monitor egg clutches and tadpole development daily to build a stable founding population. As reported by Mongabay’s 2024 conservation update, these facilities represent the first coordinated effort to save the skeleton frog ex-situ—an experiment in rebuilding a species from the last survivors left.

4. Restoring its forest home remains the second priority.

Saving the frogs in tanks is only a temporary fix. Conservation teams are replanting native vegetation, stabilizing stream banks, and removing invasive plants that alter water chemistry. Without cool, shaded pools, reintroduction would be futile. Local forestry cooperatives are also being trained to monitor logging activity and safeguard reforested corridors. In this effort, biology meets community action—scientists provide the expertise, but long-term guardianship lies with the people who share the forest.

5. Hidden threats include disease and isolation stress.

Amphibians across Madagascar face rising infection risks from chytrid fungus, and skeleton frogs are no exception. The breeding program includes strict quarantine, with every wild-caught individual tested before entry. In captivity, stress can also trigger hormonal changes that affect breeding success. Keepers now use low-light environments and natural soundscapes to reduce anxiety in these high-strung amphibians. Their approach blends laboratory precision with environmental empathy—a delicate balance between science and survival.

6. Genetic bottlenecks complicate the rescue effort.

With so few founders, genetic diversity becomes the next concern. Biologists collect DNA samples from each frog to manage pairings and avoid inbreeding depression. Genetic health determines resilience—without it, future offspring may struggle to survive once reintroduced. Conservationists are exploring ways to locate any remnant wild individuals that could expand the gene pool. Every additional frog found becomes a thread to strengthen this fragile genetic fabric.

7. Local villagers are joining the conservation network.

Communities near Sahamalaza are being trained to act as forest stewards, monitoring water quality and reporting habitat destruction. Conservationists emphasize education: protecting the skeleton frog means safeguarding the same rivers that sustain crops and livestock. Involving residents transforms the project from an external intervention into a shared mission. When the people living closest to the problem become the protectors, success stops being theoretical—it becomes cultural.

8. Plans for reintroduction are already on the horizon.

If captive-bred frogs reach maturity and pass health checks, the first trial reintroductions could occur within three years. Scientists will release them into restored stream sections under round-the-clock monitoring. Each phase builds on lessons learned from earlier amphibian programs in Madagascar, where small, adaptive releases have proven safer than mass introductions. The goal is not just survival—it’s integration, to see the frogs breeding in the wild again without constant human intervention.

9. Funding stability remains a looming challenge.

Short-term grants have kept the project afloat, but researchers admit that sustained success depends on long-term financial support. Facility maintenance, reforestation, and community engagement all require continuity. Conservation fatigue is an ever-present threat, especially for lesser-known species that lack the charisma of lemurs or tortoises. Advocates are now working to build international partnerships to secure multi-year commitments before the next field season begins.

10. The skeleton frog’s survival carries a deeper message.

This single species, translucent and almost invisible in the forest, has become a symbol for the broader amphibian crisis unfolding worldwide. Its rescue is about more than one frog—it’s about preserving the living pulse of Madagascar’s streams, forests, and ecosystems intertwined with them. Scientists say if the skeleton frog can recover, it will prove that even the smallest, most fragile lives are worth saving. And maybe, that success will echo far beyond one corner of the forest.