Ancient stories of sunken continents continue to shape modern culture.

The names Atlantis and Lemuria conjure visions of vanished civilizations, swallowed by oceans and remembered only in myths. For centuries, they’ve been treated as tantalizing clues that maybe history is incomplete, that entire worlds could vanish without a trace. The allure isn’t just about ruins and treasure, it’s about what their survival in story form says about human imagination.

Despite repeated debunking by scientists, the tales refuse to fade. Writers, spiritualists, and conspiracy theorists keep them alive, reshaping the legends for each generation. What lingers is not evidence of lost continents, but something more enduring, the power of myth to blend scraps of geology, philosophy, and cultural longing into stories that refuse to die.

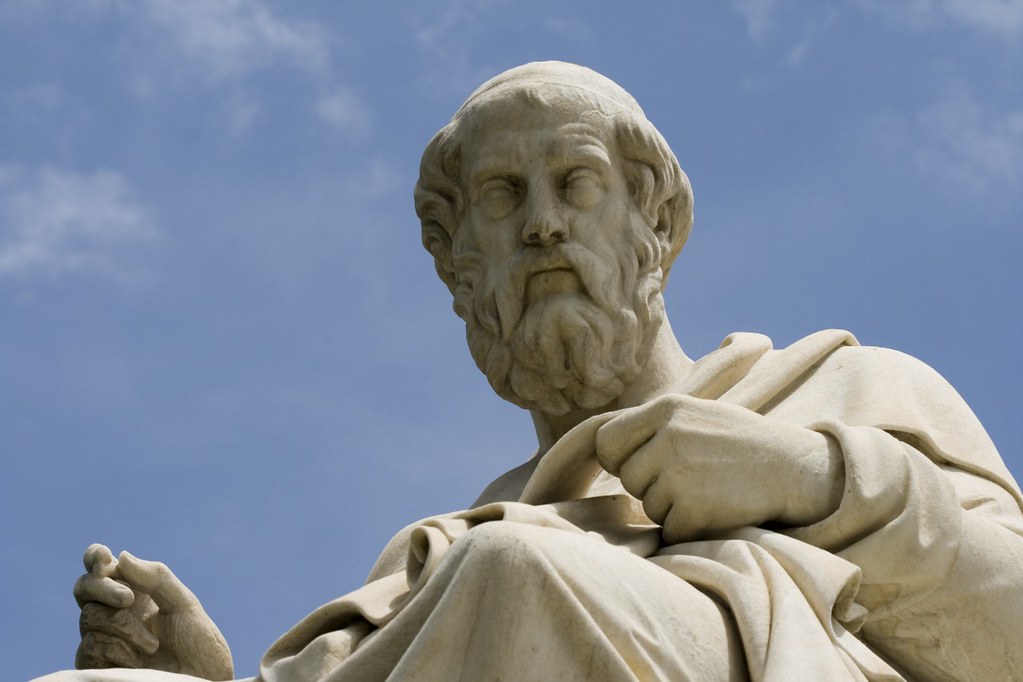

1. Plato planted the seed of Atlantis and scholars never let go.

The earliest detailed account of Atlantis comes straight from Plato, who used it in his dialogues “Timaeus” and “Critias” around 360 BCE. Historians widely agree he meant it as an allegory about hubris and the fate of powerful societies. Yet once the idea entered the written record, it became impossible to confine to philosophy. Generations of scholars, explorers, and adventurers treated it as a puzzle worth solving, scouring coastlines from the Mediterranean to the Caribbean. The University of Cambridge’s archives note how even respected Renaissance thinkers debated its reality as if it were geography, not metaphor.

That blurred line between parable and possibility gave the myth remarkable staying power. Instead of fading as a cautionary tale, Atlantis morphed into a half-serious historical riddle. By the Enlightenment, it was already a cultural touchstone, reappearing in travel accounts, theological debates, and eventually pseudoscience.

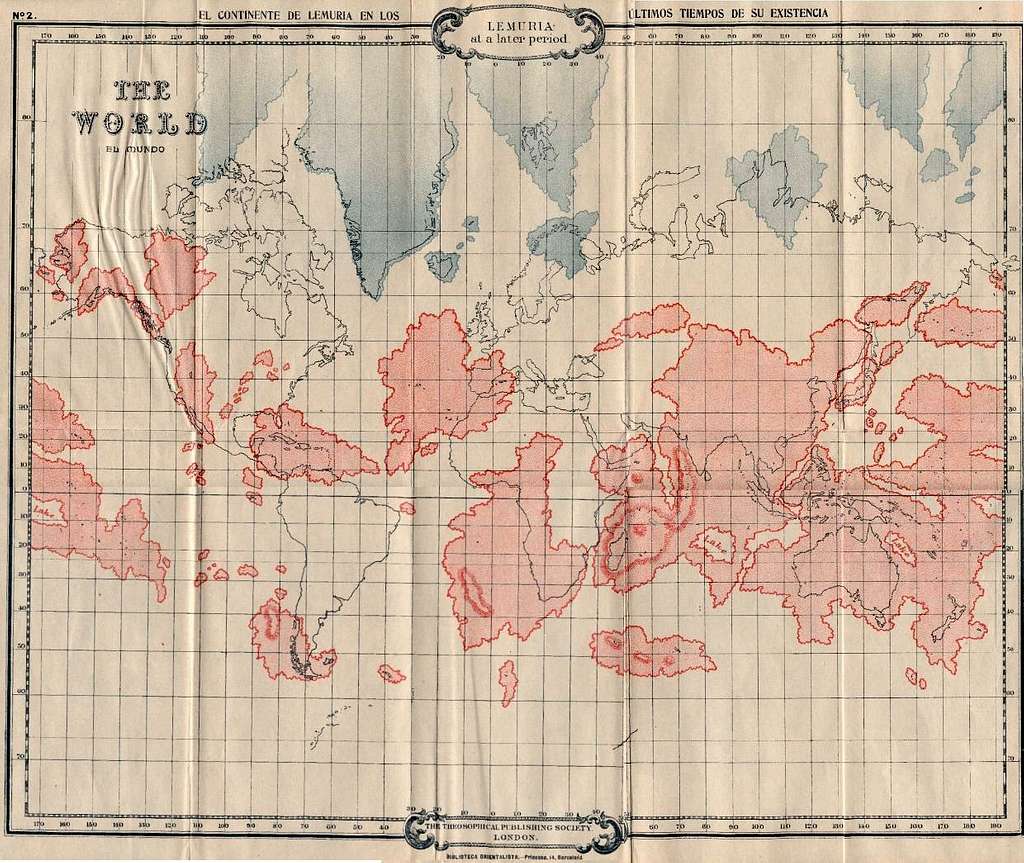

2. Lemuria was born not from folklore but from zoology.

Unlike Atlantis, which came out of philosophy, Lemuria started with 19th century natural science. In 1864, zoologist Philip Sclater noticed lemurs existed in both Madagascar and India but not in Africa or the Middle East. To explain the distribution, he proposed a now-extinct land bridge across the Indian Ocean. What began as a scientific guess took on a mythic dimension once popular writers latched onto the name. They began weaving tales of ancient civilizations thriving on this lost landmass, as stated by the Geological Society of London.

Even after plate tectonics replaced land-bridge theories, the story had already spiraled into spiritualist lore. Theosophists in particular gave Lemuria a mystical spin, imagining it as the cradle of humanity. Science moved on, but the legend had already slipped free of its origin.

3. Victorian spiritualists turned speculation into scripture.

In the late 1800s, Theosophical writers like Helena Blavatsky seized on Lemuria, blending it with esoteric traditions to claim it was home to “root races” of humanity. This was less about geology than about constructing a spiritual origin story. Reported by Smithsonian Magazine, Blavatsky’s “The Secret Doctrine” turned pseudoscience into cosmic narrative, embedding Lemuria into a theology that appealed to readers searching for meaning outside traditional religion.

The timing mattered. Darwin’s theory of evolution was shaking religious faith, and Lemuria offered a mystical middle ground. Suddenly, it wasn’t just a bridge for animals—it became a lost Eden for humans. This spiritual rebranding is why Lemuria, despite being disproven in science, never disappeared from cultural memory.

4. Atlantis soon became a canvas for every utopian dream.

As the 20th century began, Atlantis no longer belonged to philosophers or scientists—it became a playground for visionaries. Writers recast it as a society of perfect technology, sometimes spiritual, sometimes mechanical, depending on the anxieties of the moment. In the early Cold War, some even imagined it as proof of ancient nuclear disasters, foreshadowing humanity’s own self-destruction. The story became less about what was lost and more about what people wished had once existed.

This ability to reflect cultural hopes and fears explains why Atlantis never vanished. Each generation reinvented it to mirror its own worries, from technological excess to ecological collapse.

5. Nazi ideology twisted both myths into propaganda.

During the 1930s, Nazi occultists latched onto Atlantis and Lemuria, using them to imagine a prehistoric Aryan homeland. These pseudo-histories offered a false legitimacy to racial hierarchies. They scoured Tibet and the Arctic, chasing signs of a lost master race. The myths, once philosophical curiosities and spiritual experiments, were repurposed into tools of political violence.

This darker chapter underscores how malleable myths can be. The same stories that inspired utopian speculation also provided cover for pseudoscience and hate. Myths that promise identity and origin can be powerful, but they can also be dangerous.

6. Hollywood transformed Atlantis into spectacle instead of philosophy.

The film industry wasted no time converting myths into box office gold. Atlantis appeared in early silent films, later animated features, and even blockbusters. Each version ditched Plato’s warning in favor of adventure, romance, or sci-fi flair. Audiences didn’t want allegory—they wanted glowing crystals, sunken temples, and explorers dodging disaster.

That cinematic shift cemented the myths as entertainment rather than intellectual puzzles. Once Atlantis had been dressed in art deco submarines and CGI, it was less about history than about how far fantasy could go on screen.

7. Science fiction writers made Lemuria into cosmic territory.

While Hollywood favored Atlantis, pulp fiction magazines in the early 20th century gave Lemuria a second life. Writers like H. P. Lovecraft and others folded it into their fictional universes, connecting it to alien races and forbidden knowledge. What had begun as a zoologist’s hunch now lived on as a stage for horror and interplanetary drama.

These pulp stories ensured that Lemuria wouldn’t be forgotten. Instead of fading with advances in geology, it gained fresh vitality in the imagination of readers who craved strange worlds and darker mythologies.

8. New Age movements kept the legends alive in the 1970s.

As interest in astrology, crystals, and meditation surged, Atlantis and Lemuria found new audiences. Spiritual writers claimed that survivors had passed down wisdom through hidden teachings, waiting to be rediscovered. Retreats in California and Hawaii even marketed themselves as places to reconnect with the lost continents through guided meditation.

By this point, the myths were no longer about evidence. They were about identity, self-discovery, and alternative spirituality. In a society weary of political unrest and materialism, Atlantis and Lemuria offered mystery that felt personal and empowering.

9. Internet forums and YouTube gave the myths a global revival.

The rise of digital culture in the late 1990s and 2000s sparked another wave of interest. Suddenly, theories about Atlantis in the Caribbean or Lemuria under the Pacific could reach millions overnight. Videos blended pseudo-archaeology with CGI reconstructions, while forums debated sonar scans and satellite photos.

Even skeptics couldn’t keep up with the sheer volume of content. What used to circulate in niche books now lived in searchable databases, amplifying the myths for an entirely new generation.

10. The endurance of these stories says more about us than lost continents.

What makes Atlantis and Lemuria endure isn’t evidence but longing. People want their world to hold mysteries, to imagine that beneath the ocean lies proof of civilizations as wise or as foolish as our own. The myths persist not because they’re true, but because they scratch a human itch for wonder.

Ultimately, they survive as mirrors. When people talk about Atlantis and Lemuria, they are often talking about themselves—their fears of collapse, their hunger for meaning, their hope that history still holds secrets waiting to surface.