Scientists finally solved one of the ocean’s most devastating climate mysteries.

Between 2018 and 2021, more than 10 billion snow crabs disappeared from Alaska’s Bering Sea in what scientists now recognize as one of the largest marine die-offs ever recorded. The mystery that devastated fishing communities and baffled researchers for years has finally been solved.

The collapse wasn’t gradual or expected. One moment, the eastern Bering Sea teemed with what appeared to be a record-breaking population of snow crabs, and then they simply vanished, leaving behind empty crab pots and shattered livelihoods across remote Alaskan communities.

1. Marine heatwaves turned the crabs’ own metabolism against them.

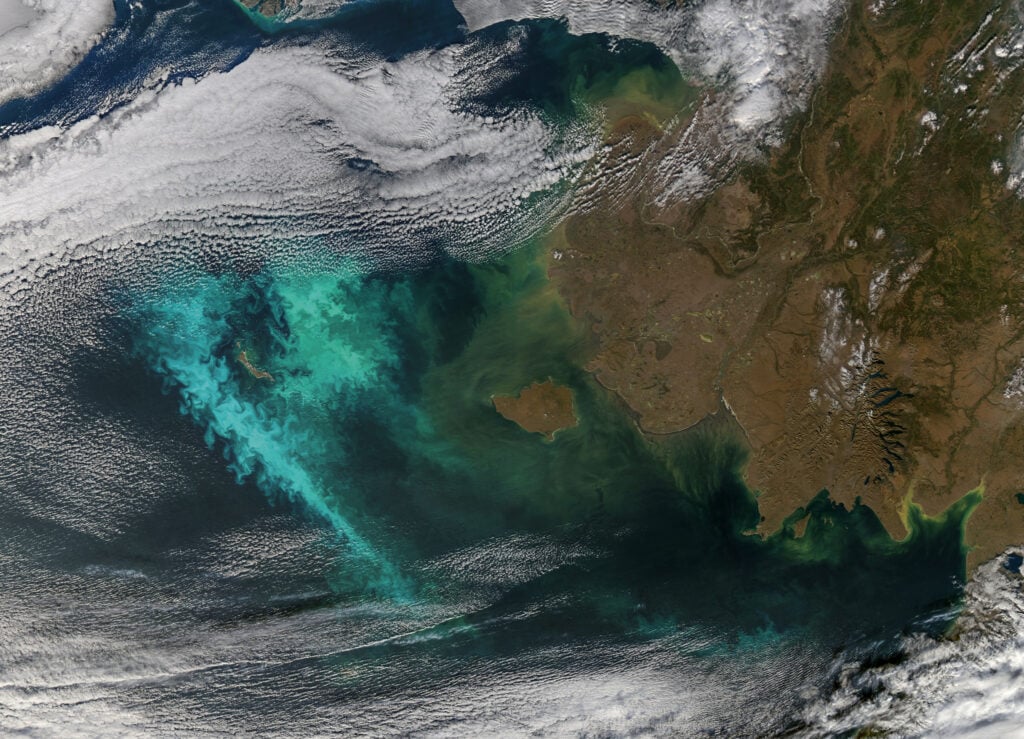

The culprit behind this massive die-off was a prolonged marine heatwave that struck the Bering Sea between 2018 and 2019, raising ocean temperatures well above normal levels. According to research published in the journal Science by NOAA scientist Cody Szuwalski and his colleagues, these elevated temperatures didn’t kill the crabs directly but instead accelerated their metabolism dramatically. Laboratory studies revealed that snow crab caloric requirements nearly doubled when water temperatures increased from just above freezing to around 37 degrees Fahrenheit.

This metabolic acceleration created an impossible energy equation for the crabs. While they could physically survive the warmer water temperatures, their bodies demanded far more food to sustain themselves than the environment could provide. The crabs essentially starved to death despite living in waters that had previously sustained them for decades.

2. A perfect crab population became a liability during the crisis.

The timing of the heatwave couldn’t have been worse for snow crab survival. Years of favorable ocean conditions had produced what scientists described as one of the largest snow crab populations ever recorded, with billions of crabs reaching maturity simultaneously, as reported by NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center. This abundance initially seemed like great news for the fishing industry and marine ecosystem.

However, when the marine heatwave hit, this massive population became a catastrophic disadvantage. The unprecedented number of crabs all competing for the same limited food sources in an environment where their energy needs had doubled created a starvation scenario that smaller populations might have survived. The very success of previous breeding seasons set up the conditions for the devastating collapse.

3. The cold pool sanctuary disappeared when crabs needed it most.

Snow crabs depend on frigid bottom waters known as the “cold pool” for their survival and development, particularly during their vulnerable juvenile stages. This essential habitat typically covers vast areas of the Bering Sea seafloor, providing the perfect conditions for crabs to grow and thrive, as documented by NOAA Fisheries researchers. During normal conditions, this cold water refuge spans thousands of square miles.

The 2018-2019 marine heatwave effectively eliminated this critical habitat, forcing crabs into increasingly smaller areas of suitable water. As their territory shrunk dramatically, millions of crabs found themselves crowded into whatever cold water remained, intensifying competition for already scarce food resources and creating perfect conditions for mass starvation.

4. Warmer waters disrupted the entire food web beneath the crabs.

The marine heatwave didn’t just affect the crabs directly but fundamentally altered the entire bottom-dwelling ecosystem they depended on for survival. Warmer water temperatures changed how organic matter settled to the seafloor, disrupting the normal flow of nutrients that feed the small organisms snow crabs rely on.

Additionally, the temperature changes affected plankton distribution and the timing of seasonal food webs, creating mismatches between when crabs needed food most and when it was available. This ecosystem disruption meant that even if individual crabs could have found enough territory, the food simply wasn’t there to support their elevated metabolic demands.

5. Scientists ruled out fishing pressure and other usual suspects.

Researchers conducted extensive analysis to eliminate other potential causes of the population collapse, including overfishing, bycatch from other fisheries, disease outbreaks, and predation by Pacific cod. Their models showed that fishing pressure had remained relatively stable for decades and couldn’t account for such a dramatic and sudden population loss.

The data also revealed that while Pacific cod populations did shift northward during the heatwave, this movement actually reduced predation pressure on snow crabs rather than increasing it. Disease and cannibalism, while present in the system, occurred at levels far too low to explain the magnitude of the die-off, leaving climate-driven starvation as the overwhelming cause.

6. This collapse mirrors similar climate disasters across Alaska’s waters.

The snow crab die-off wasn’t an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of marine heatwave impacts across Alaska’s waters. Similar events had previously devastated Pacific cod populations in the Gulf of Alaska during a 2016 heatwave, demonstrating how these temperature spikes are becoming recurring threats to cold-water species.

These parallel collapses suggest that Alaska’s marine ecosystems are entering a new era of climate-driven instability, where traditional patterns of abundance and sustainability can be shattered within just a few seasons. The snow crab disaster serves as a preview of what other Arctic and sub-Arctic species might face as ocean temperatures continue rising globally.

7. Fishing communities lost hundreds of millions in economic value overnight.

The snow crab collapse devastated Alaska’s fishing economy, eliminating what had been a $150 million annual industry that supported hundreds of boats and thousands of jobs. In 2021 alone, the fishery generated $219 million for fishing communities, making its sudden closure an economic catastrophe for entire regions dependent on crab harvesting and processing.

The town of St. Paul, home to the world’s largest crab processing facility, lost nearly 60 percent of its tax revenue immediately after the fishery closure. Community leaders declared a “cultural, social, and economic emergency” and had to launch online fundraising campaigns just to maintain basic emergency medical services, highlighting how climate impacts can destroy local economies within a single season.

8. The disaster exposed the vulnerability of Indigenous communities to climate change.

St. Paul Island, populated primarily by Unangan (Aleut) people, exemplified how climate change disproportionately impacts Indigenous communities that depend on traditional marine resources. The community had spent decades building an economy around snow crab processing after the end of commercial fur seal hunting, only to see their primary economic foundation vanish due to climate factors beyond their control.

This collapse forced many residents to consider leaving their ancestral home, threatening not just individual livelihoods but the cultural continuity of a community that has maintained its connection to the Bering Sea for thousands of years. The crisis demonstrates how climate change can erase both economic opportunities and cultural heritage in remote communities with limited alternative industries.

9. Early signs of recovery offer hope but highlight ongoing uncertainty.

Recent surveys have shown encouraging signs for snow crab populations, with cooler water temperatures returning to more normal levels and increased numbers of juvenile crabs detected in 2022 and 2023. These improvements led Alaska to reopen the snow crab fishery for the 2024-2025 season, though at dramatically reduced quotas compared to pre-collapse levels.

However, scientists warn that this recovery might be temporary, as climate models predict continued warming trends that could trigger similar collapses in the future. The current reprieve may simply represent a brief return to cooler conditions rather than a permanent solution, leaving fishing communities and crab populations vulnerable to the next marine heatwave.

10. This collapse signals a fundamental shift toward “borealization” of Arctic waters.

Scientists have identified the snow crab collapse as evidence of “borealization,” a process where Arctic marine ecosystems shift toward sub-Arctic conditions due to climate change. This transformation favors warm-adapted species while displacing cold-adapted ones like snow crabs, fundamentally altering the structure of northern marine food webs.

The shift represents more than just a temporary disruption; it signals a permanent transformation of one of the world’s most productive marine ecosystems. As the Bering Sea continues warming, the Arctic characteristics that have sustained snow crab populations for millennia may become increasingly rare, forcing both the species and the human communities that depend on them to adapt to an entirely different ocean environment.