These birds aren’t commuting—they’re out-flying the mileage on your car every single year.

Some birds don’t migrate. Others casually log tens of thousands of miles like it’s nothing. And then there are a few that basically loop the planet while you’re still trying to figure out your flight connection. These aren’t short scenic detours. These are full-scale marathons across oceans, continents, and some of the most brutal environments on Earth. Starting with the shortest of the long-distance pros, here are the ten wildest bird migrations—ending with the absolute record-holder.

10. Ruby-throated hummingbirds do a nonstop flight that defies their size.

They weigh about three grams. That’s less than a nickel. But every year, ruby-throated hummingbirds make a direct, uninterrupted flight across the Gulf of Mexico, covering around 500 miles in one stretch. They don’t land. They don’t eat. They just go. As stated by the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, they double their body weight beforehand by loading up on nectar and sugar-rich bugs to survive the trip. It’s like a sugar-fueled cannonball run across open water, powered entirely by wings flapping 50 times per second.

9. Blackpoll warblers cross the Atlantic with no land in sight.

They look like ordinary songbirds, but they pull off one of the most intense migrations in the bird world. Blackpoll warblers launch from the northeastern U.S. or Canada and fly 1,800 to 2,200 miles straight over the Atlantic to reach South America. According to researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, this flight can last up to three days nonstop. No food, no breaks, just endurance. They burn half their body mass mid-flight. And when they land, they do it like nothing happened.

8. Bar-headed geese make Himalayan peaks look like hills.

You’d think Mount Everest would be a problem. Not for bar-headed geese. These birds are known for flying over the Himalayas at altitudes higher than most commercial aircraft, often above 27,000 feet. As discovered by scientists from the University of British Columbia, their blood chemistry allows them to extract oxygen efficiently from thin air. Their seasonal migrations span 3,000 to 4,000 miles, including high-altitude stretches so dangerous most species wouldn’t even attempt it. They just cruise past the world’s tallest peaks like they’re not even there.

7. Snow buntings head toward colder places when others are escaping them.

They migrate from Arctic Canada to parts of northern Russia and back again, covering around 4,300 to 5,000 miles annually. What makes snow buntings different is they actively seek out the cold. Instead of avoiding winter, they move with it, tracking snow lines and choosing icy landscapes as their seasonal destinations. Their bodies are built for brutal wind and freezing temperatures. Other birds migrate to avoid discomfort. Snow buntings migrate to stay in it.

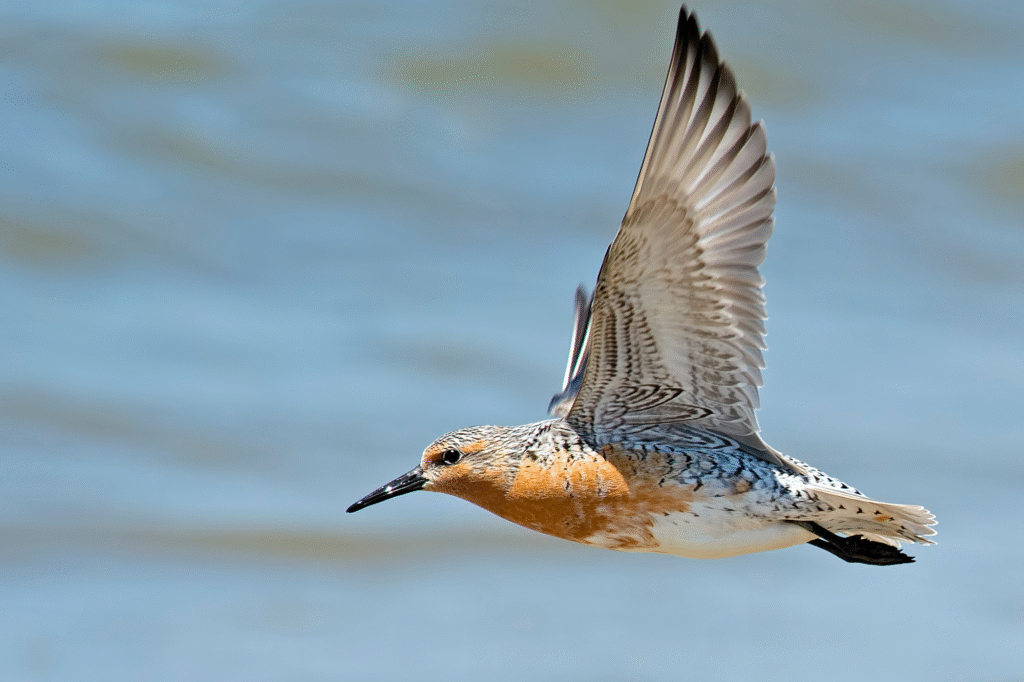

6. Red knots sync their timing with ancient sea creatures to fuel their trip.

Red knots travel around 9,300 miles one-way from Tierra del Fuego in South America to the Canadian Arctic. That’s wild on its own, but it gets more precise. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, their entire migration is timed to match the spawning of horseshoe crabs in Delaware Bay. Miss that window, and the birds risk running out of fuel. Hit it perfectly, and they binge on eggs before finishing the journey north. It’s a long flight with one weird, critical pit stop.

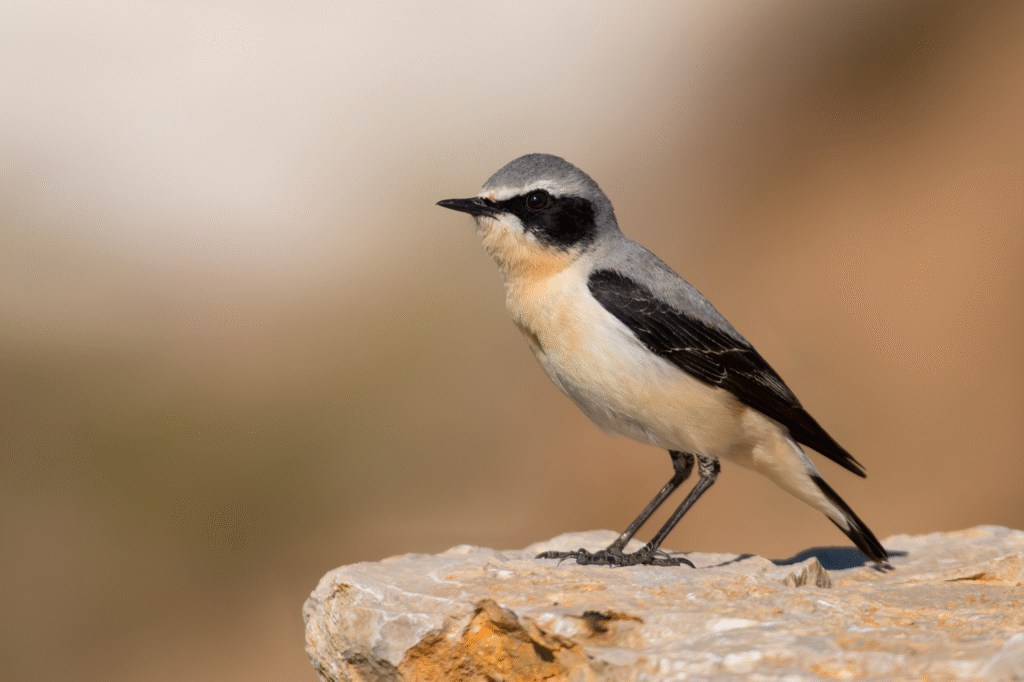

5. Northern wheatears quietly rack up over 18,000 miles a year.

They don’t look like record-breakers, but northern wheatears are tiny birds that make a huge loop. Birds breeding in Alaska migrate across Asia, while those from Europe head through Africa. Either way, they rack up roughly 9,000 miles each way. Their total annual travel distance hovers between 18,000 to 20,000 miles. They don’t show off. They don’t make headlines. They just disappear and show up again thousands of miles later like nothing happened. It’s the most low-key migration flex on this list.

4. Sooty shearwaters basically fly laps around the entire Pacific Ocean.

These seabirds clock in an annual migration of about 40,000 miles, looping from New Zealand to the North Pacific and back. They’re not just commuting—they’re completing figure-eight routes that cover most of the ocean. They ride prevailing winds and weather systems to conserve energy, cruising for thousands of miles at a time. They disappear into the open sea for months, showing up on the other side of the planet like it was the most casual errand ever.

3. Arctic terns chase summer and light across the entire globe.

This bird holds the record for the longest known annual migration in terms of straight-line distance. Arctic terns travel from their Arctic breeding grounds all the way to Antarctica and back again, averaging around 50,000 miles each year. As reported by the American Museum of Natural History, they zigzag across oceans to follow wind patterns, not just straight routes. In doing so, they experience more daylight than any other species on Earth. It’s not just about surviving—it’s about thriving under two summers a year.

2. Common swifts stay in the air so long it’s hard to track how far they’ve gone.

Distance numbers are tricky with these birds, but the time they spend airborne is unmatched. Common swifts have been tracked staying aloft for up to 10 months straight. They eat, sleep, and mate in flight. While precise annual distance varies, some estimates put their yearly mileage well above 100,000 miles. Scientists still debate the exact number, but one thing’s certain: no other bird lives this much of its life off the ground. You can’t compete with that.

1. The red-necked phalarope wins for looping oceans like it’s doing laps for fun.

This unassuming little shorebird racks up a staggering 16,000 to 22,000 miles annually, and it doesn’t even look like an athlete. Red-necked phalaropes breed in the Arctic, then head out over the open ocean, sometimes traveling from Alaska across the Pacific and down the west coast of South America. Some even take Atlantic routes to Arabian Sea wintering grounds. Their migration path loops across entire hemispheres in broad circles. They ride ocean currents like highways and do it all while looking delicate. But in terms of pure distance over water, these tiny birds might just be the ones to beat.