These artifacts could rewrite what we know about creativity.

Archaeologists in East Africa have discovered a remarkable set of bone tools dating back about 1.5 million years, reshaping what we know about early human innovation. Unearthed near the Lake Victoria basin, the tools show clear evidence of deliberate shaping and specific use, suggesting that our ancestors were already thinking creatively about how to control their surroundings. Long before stone tools became the focus of human evolution, these early makers were experimenting with new materials, passing on knowledge, and developing a level of intentional design that blurs the line between raw survival and the earliest spark of human invention.

1. The tools were unearthed near Kenya’s Lake Victoria basin.

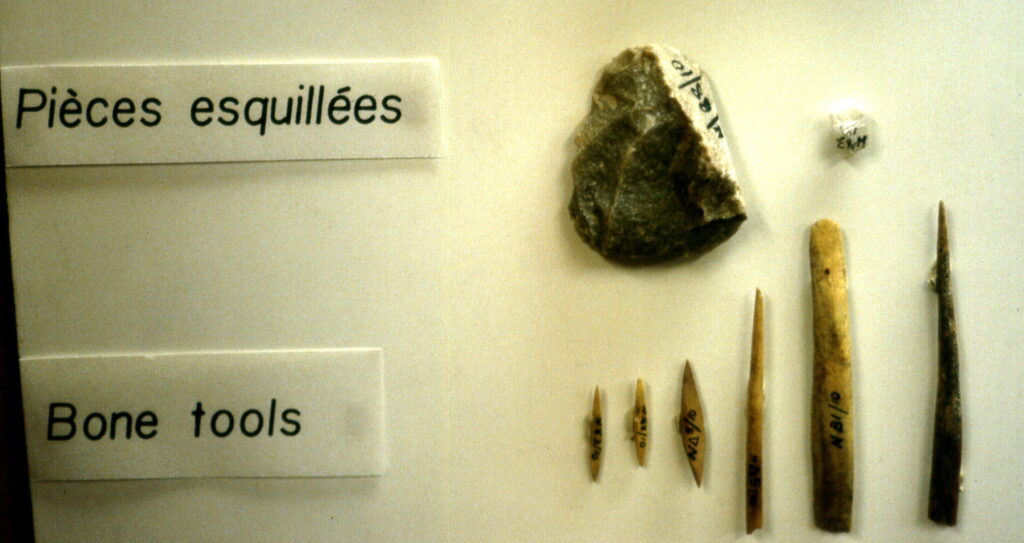

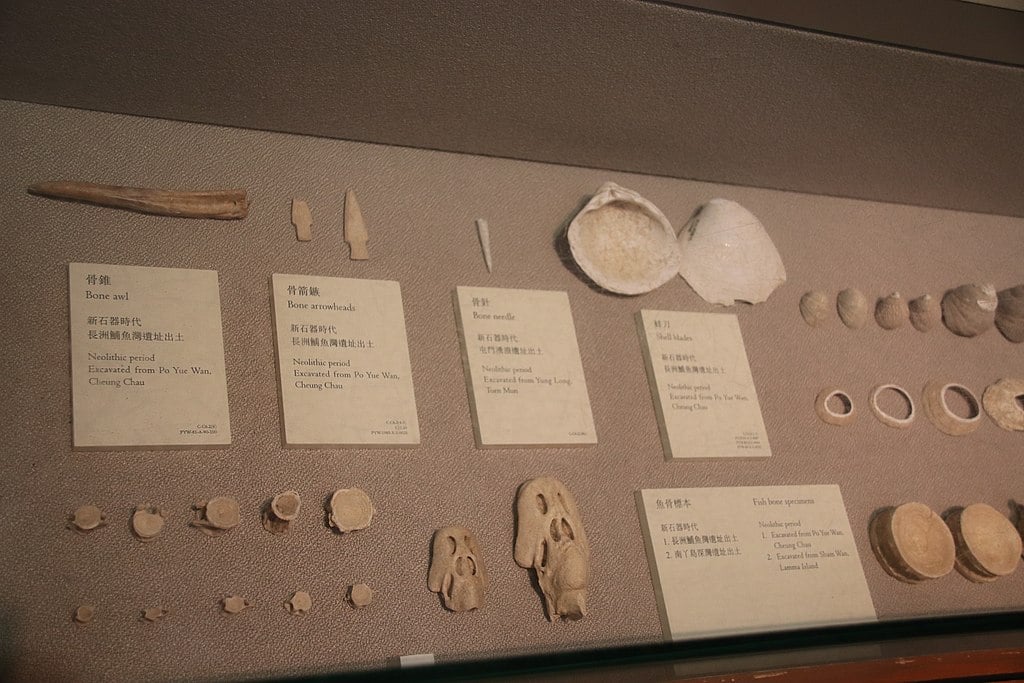

Researchers uncovered the tools at the site of Kokiselei, a region already famous for early stone artifacts. But this new layer contained bones shaped by deliberate cutting and scraping marks, distinct from natural fractures. According to a study published in Nature Communications, microscopic analysis confirmed these were not random breaks but signs of controlled shaping. The discovery adds an entirely new dimension to what we know about hominin behavior in this area, showing a level of skill and planning once thought to have developed much later in time.

2. The bone tools were likely made by Homo erectus.

While no direct fossils were found alongside the tools, the dating aligns with known Homo erectus activity in the region, as stated by the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program. This species was already using fire and building rudimentary shelters, but the addition of bone crafting changes how we understand their intelligence. These tools reveal a mind capable of abstraction—selecting materials, shaping them for purpose, and repeating successful designs. That kind of pattern-based thought is what separates invention from instinct, a small but monumental leap in our evolutionary story.

3. The bones were used to shape hides and carve meat.

Analysis of wear patterns showed repetitive scraping motions consistent with processing animal hides or stripping meat, reported by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. The smooth polish along certain edges suggests repeated use, implying they weren’t one-time experiments but reliable household tools. This finding adds context to how early humans managed resources—turning hunting leftovers into functional instruments. It hints at an early form of recycling, long before we had words for sustainability or efficiency, yet both were instinctively practiced by our ancestors.

4. These discoveries challenge the dominance of stone tools.

For decades, stone tools were considered the pinnacle of early human technology. The idea that bone tools existed alongside or even before them rewrites that timeline entirely. Bones are softer and harder to preserve, which means we may have underestimated their role simply because fewer survive. Their existence suggests creativity wasn’t confined to a single medium but explored through available materials, from rock to bone to wood—each serving a purpose in shaping the survival toolkit of early hominins.

5. They show evidence of deliberate selection and refinement.

The makers didn’t just grab any bone lying around. They chose pieces with density and shape that could handle repeated motion without cracking. The repeated patterns of sharpening show a level of understanding about durability and ergonomics. It wasn’t luck; it was learned behavior. That knowledge likely spread within small groups, signaling a rudimentary form of cultural transmission—one of the earliest examples of shared technology and teaching between individuals.

6. Marks of planning suggest a leap in cognition.

Every incision and groove points to forethought. Rather than reacting to immediate needs, these toolmakers seemed to anticipate future tasks. They shaped and stored tools for later use, an enormous cognitive step beyond simple survival. Planning implies memory, imagination, and an awareness of time—all qualities tied to modern human intelligence. It’s possible that this foresight, born from practical necessity, was the seed of what would later become human innovation and strategy.

7. The find expands how we define early technology.

Technology is often equated with metal or stone, but this discovery redefines it as any intentional adaptation of the natural world. Bone tools broaden the framework, showing that early humans saw potential in organic materials. They were already engineers in their environment, solving problems with whatever was available. This adaptability laid the foundation for all later inventions—proof that creativity isn’t about the material itself, but the mind that envisions its use.

8. Microscopic evidence reveals the first signs of craftsmanship.

Under magnification, researchers found repeated, symmetrical etching marks consistent with controlled shaping motions. The edges weren’t random or crude—they were refined through trial and error. Such precision suggests these tools weren’t accidents but designed for repeated utility. In a sense, this may represent the birth of craft: not just making something to survive, but improving it for better performance. The earliest workshop might have been a riverside, with bone shards scattered beside ancient footprints.

9. This could mark the start of symbolic behavior.

Some archaeologists believe shaping bone had symbolic meaning—perhaps pride in creation or recognition of a personal tool. The act of design might have carried more than function; it could have reflected identity or group knowledge. Even if subtle, this emotional layer represents a deeper shift in consciousness. The same impulse that led a hominin to perfect a scraper could have eventually inspired cave paintings, jewelry, or storytelling thousands of years later.

10. The discovery hints that invention began earlier than thought.

If these tools indeed predate other known artifacts, they might represent the very first moment humanity stepped beyond instinct into invention. That means our ancestors were thinking creatively 500,000 years earlier than once believed. It reframes human history—not as a sudden spark of intelligence, but a slow, beautiful burn of curiosity and adaptation. Somewhere in that ancient dust, the first idea was born, and everything since—fire, writing, art—has been a continuation of that same spark.