Rare merchant ship discovered nearly 2.6 kilometres underwater.

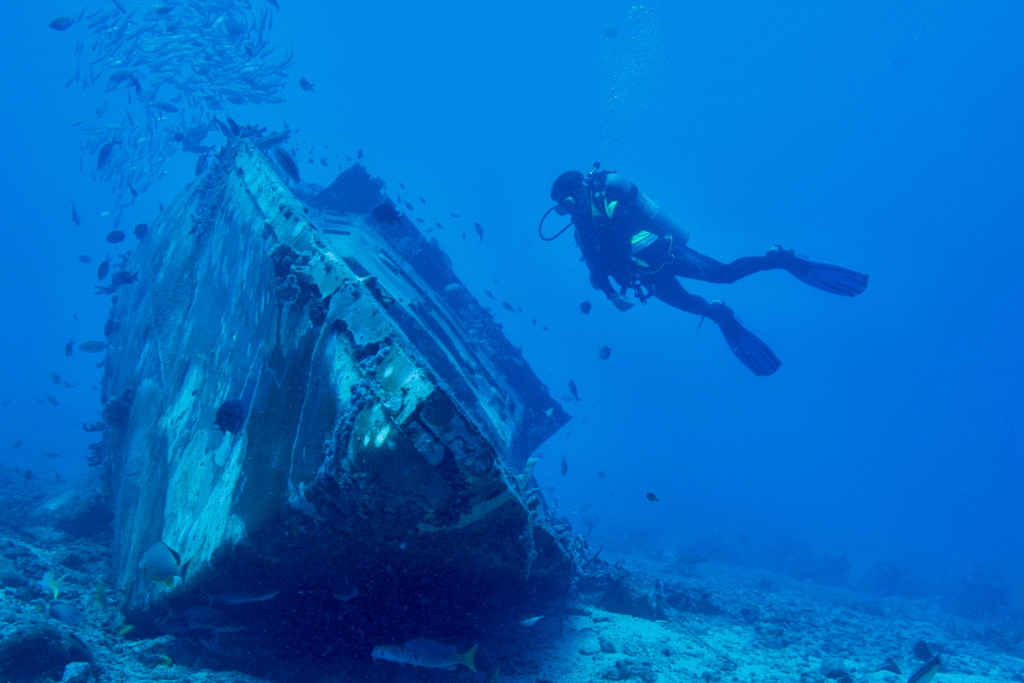

In March 2025 an underwater drone mapping the Mediterranean seabed off southeastern France captured images of an astonishing find: a 16th-century merchant ship, later named Camarat 4, resting some 2,567 metres (approximately 8,420 feet) below the sea surface. The ship sits untouched and extraordinarily well-preserved in near-total darkness, carrying a cargo of ceramics, metal bars and anchors that illuminate the maritime trade of half a millennium ago. This discovery opens a new chapter in underwater archaeology and offers a rare window into trade, technology and shipbuilding of the early modern Mediterranean.

1. The ship was found at a record depth for Mediterranean archaeology.

During a routine French Navy seabed mapping mission, sonar picked up a large wreck lying deep beneath the water near Ramatuelle, and subsequent imaging confirmed the vessel lay at around 2,567 metres depth—making it the deepest known shipwreck in French territorial waters, as reported by Smithsonian. This depth means the ship has been shielded from trawlers, looters and most natural decay processes, effectively preserved in a time capsule on the sea floor. For archaeologists this level of preservation is extremely rare, as most wrecks from the era lie in much shallower water and suffer human or environmental interference.

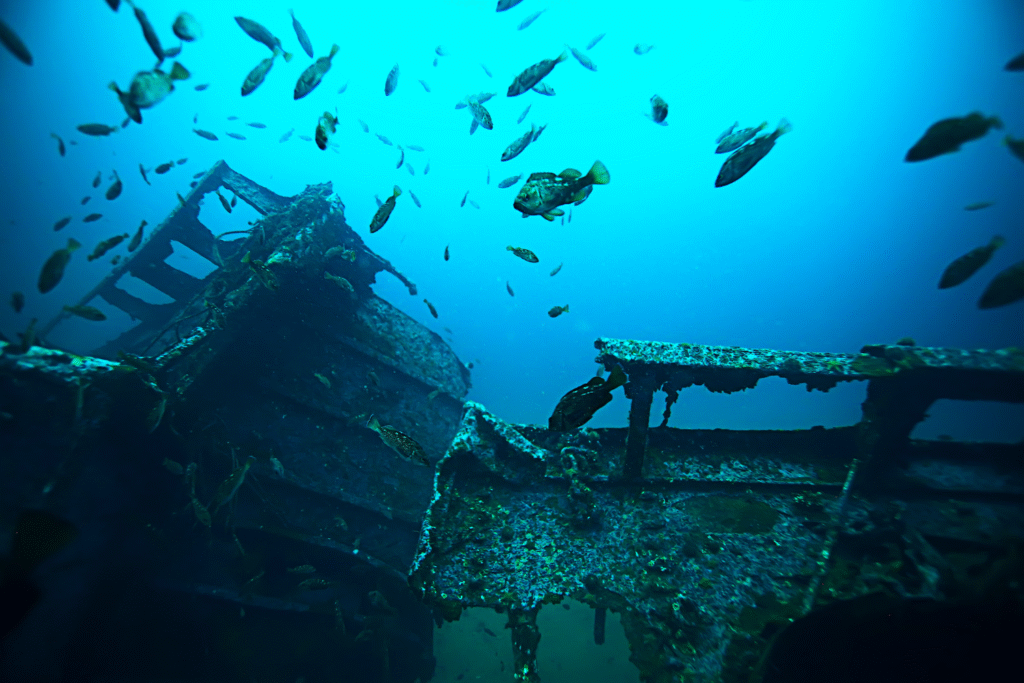

2. It carried hundreds of ceramic jugs and other goods from the 16th century.

Evidence from the site shows the ship, likely bound from northern Italy to another Mediterranean port, was transporting decorated ceramic jugs, yellow glazed plates and metal bars when it sank, according to Archaeology Magazine. The cargo reveals not just trade in common utilitarian goods but also materials suitable for more specialised markets. Findings such as religious symbol-decorated pitchers and iron bars hint at a complex merchant route and suggest that this ship was part of a well-organised trade network in the early modern era.

3. The wreck offers exceptional preservation rarely seen at such depth.

Because the wreck lies in the near-total darkness and high pressure of deep-sea conditions, it has avoided many of the biological and human disturbances that affect shallower shipwrecks, as discovered by Popular Science. Wooden timbers, ceramics and metal artifacts remain intact, giving researchers unusually complete information about the vessel’s cargo, construction and sinking. The lack of wood-boring organisms, minimal sediment shift and no evidence of large-scale salvage make Camarat 4 a near-pristine archaeological site—granting a richer story than the majority of shipwrecks ever studied.

4. Its construction and design reflect 16th-century Mediterranean merchant practices.

Wooden planks, fastenings and rigging visible in the images suggest the ship was built in line with Mediterranean merchant vessel traditions of the era. Its dimensions—about 30 metres long and 7 metres wide—fit the profile of large coastal trading ships that carried heavy cargo yet still navigated shallow ports. The presence of cannons found near the wreck also indicates that merchant vessels were armed against piracy even then. This combination of size, cargo and defensive equipment paints a vivid picture of early modern maritime commerce.

5. The cargo route ties northern Italian manufacturing to wider trade networks.

Analysis of the ceramics and metal bars suggests they originated in Liguria, northern Italy, and were destined for Mediterranean markets. The yellow glazed plates, jugs with pinched spouts and metal bars all hint at a supply chain extending from manufacturing hubs to coastal consumers. The ship thus represents not just a wreck, but a snapshot of pre-industrial globalisation in the Mediterranean: raw materials, finished goods and armed merchant shipping all part of a web of trade that laid the foundation for modern commerce.

6. The circumstances of the sinking remain uncertain and intriguing.

At this depth, direct investigation is challenging, but image data show the ship lying upright with its cargo largely undisturbed. Some researchers speculate it may have capsized during a storm or struck submerged terrain, while others point to possible structural failure under heavy load. No signs of battle damage or salvage efforts are visible. The intact nature of the wreck means it offers an unusually clean scenario for forensic maritime archaeology—virtually a frozen moment in time awaiting careful study.

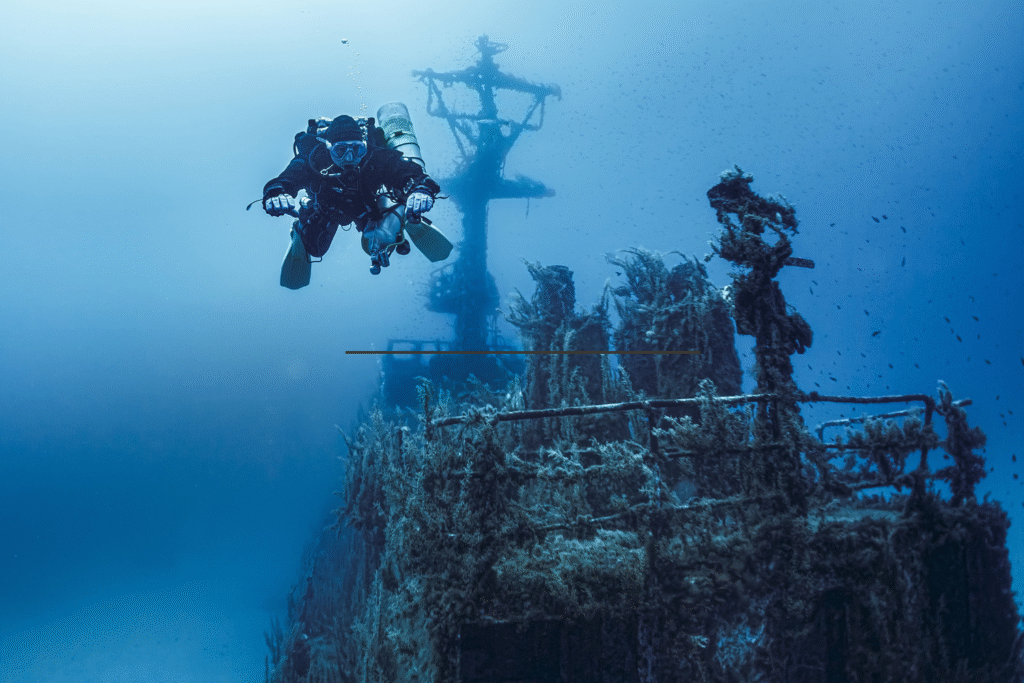

7. The find challenges notions of how many historical ships survive deep underwater.

Most known merchant shipwrecks from the 16th century lie in shallower waters and are heavily looted or degraded; this one shows what lies beyond conventional search depths. Its existence suggests that many historical vessels may survive undiscovered in deep-sea environments, shielded from human reach. The discovery encourages archaeologists to rethink depth zones previously considered inaccessible or unproductive for historical shipwrecks and to invest more in deep-water exploration.

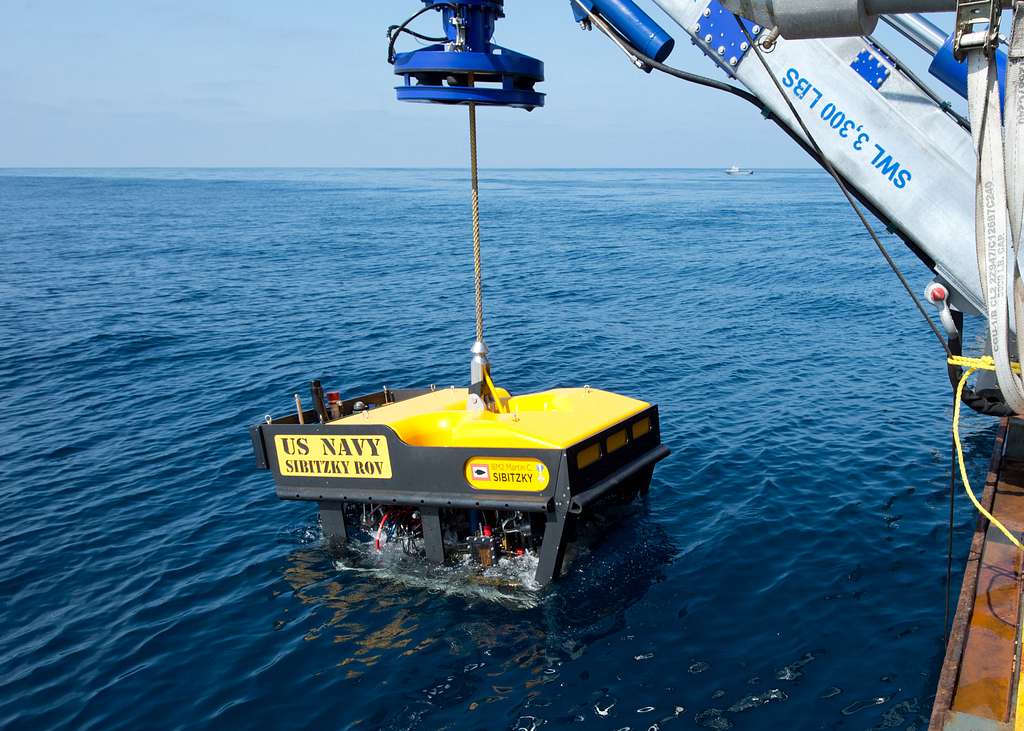

8. Technology played a crucial role in locating and documenting the wreck.

A remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and advanced sonar were key in identifying the wreck site. The French Navy’s use of seabed mapping for resource monitoring allowed for incidental discovery of the ship, and archaeologists are now creating a high-resolution 3D digital twin of the wreck for study. Such methods allow detailed examination without disturbing the site—a strategy increasingly vital for preserving deep-sea cultural heritage.

9. Conservation ethics are guiding how the site will be studied.

Rather than raising artifacts or disturbing the hull, French authorities and maritime archaeologists have emphasised in-situ preservation to minimise damage. The site’s depth makes physical recovery difficult and risky, so the focus is on remote observation, minimal intervention and long-term monitoring. This approach reflects evolving standards in underwater archaeology that prioritise preservation over collection when possible.

10. The discovery enhances our understanding of early modern maritime trade.

By offering a largely intact example of a merchant vessel loaded with cargo, the Camarat 4 wreck advances knowledge of shipbuilding, trade logistics and maritime culture in the 16th century. It provides historians and archaeologists with data on material culture, trade relationships and the risks faced by seafaring in the early modern period. Beyond its depth record, the wreck opens a broader narrative of commerce, empire and seafaring that shaped the modern world’s economic foundations.