A single cave wall changes how early humans are understood.

Deep inside a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, a faded red scene has been re dated and reinterpreted in ways that force scientists to rethink when humans first began telling stories. The painting shows a large animal and several human like figures interacting in a shared space. New analysis places its creation more than fifty one thousand years ago. That makes it the oldest known narrative artwork ever identified, older than any comparable scene in Europe.

1. A remote Sulawesi cave preserves an early scene.

The painting is located in Leang Karampuang, a limestone cave in the Maros Pangkep karst region of South Sulawesi. This area has long been known for prehistoric rock art, but this particular panel stands apart because it depicts multiple figures interacting rather than a single animal. A wild pig dominates the scene, while three smaller human like figures appear positioned around it in a way that suggests coordination or observation.

What changed its importance was new dating work on mineral deposits that formed on top of the paint. These deposits provide a minimum age for the artwork. According to Nature, the calcite layer began forming at least fifty one thousand two hundred years ago. Because the paint had to exist before the mineral crust developed, the artwork itself must be older. This places narrative imagery far earlier than previously confirmed anywhere in the world.

2. Advanced dating techniques clarified the timeline.

Earlier estimates of Sulawesi rock art relied on broader dating methods that left room for debate. Researchers recently applied laser ablation uranium series dating, which allows scientists to analyze microscopic layers within calcite formations. This approach avoids averaging large samples and instead targets precise growth stages, increasing accuracy in humid tropical environments.

The results removed much of the uncertainty surrounding the artwork’s age. As reported by Griffith University researchers involved in the project, the calcite growth patterns show that the crust formed tens of thousands of years earlier than expected. This method does not date the paint directly, but it firmly establishes a minimum age that exceeds all previously confirmed narrative cave art. The technique is now expected to be applied to many other sites across Southeast Asia.

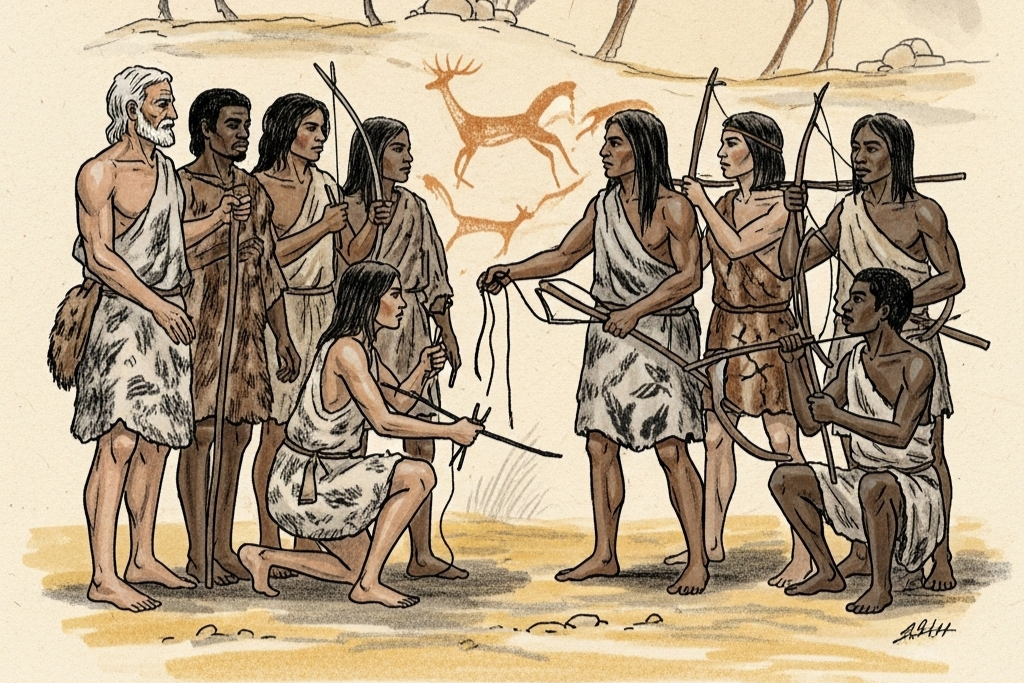

3. The composition indicates narrative intent.

What distinguishes this painting from earlier symbolic marks is the way figures relate to one another. The human like forms are not random additions. Their scale, placement, and orientation toward the pig imply an organized scene. This arrangement suggests an event unfolding rather than a decorative motif or isolated animal depiction.

Researchers argue this spatial relationship reflects narrative thinking. As stated by scientists writing in Science Advances, narrative imagery requires the ability to represent interactions across time, not just objects. This cognitive skill implies advanced symbolic reasoning. The Sulawesi scene therefore provides evidence that humans in this region were already capable of abstract storytelling tens of thousands of years earlier than previously documented.

4. Southeast Asia emerges as a creative center.

For decades, Europe dominated discussions of early symbolic behavior due to sites in France and Spain. The Sulawesi discovery shifts that geographic focus. It shows that complex visual storytelling was not confined to Ice Age Europe and likely developed independently in different regions.

This finding encourages a more global view of early human culture. Rather than a single origin point for symbolic expression, creativity appears wherever humans settled long enough to develop shared traditions. Sulawesi now stands alongside Europe as a major location for understanding how early humans thought, communicated, and remembered their experiences through images.

5. Tropical conditions helped seal the artwork.

Preservation in tropical environments is typically poor, making the survival of this painting remarkable. In Sulawesi, slow mineral seepage through limestone created thin calcite layers that protected the pigment from erosion and microbial damage. These layers acted as a natural archive.

The same process that preserved the art also made it datable. Each mineral layer represents a distinct period of formation, allowing scientists to reconstruct a timeline. This dual role of preservation and dating explains why Southeast Asian caves are now producing discoveries that rival those found in cooler climates.

6. The pig reflects ecological importance.

Wild pigs appear frequently in Sulawesi cave art, indicating their importance to early human communities. The animal in this scene is depicted with careful attention to body shape and posture, suggesting close familiarity. It was likely a key food source and possibly held cultural significance.

By placing the pig at the center of the scene, the artist emphasized its role within human life. The surrounding figures reinforce the idea that the animal was part of a shared experience. This focus reveals how early humans organized their understanding of the environment around species that directly affected survival.

7. Storytelling existed long before settlements.

This painting predates agriculture, permanent housing, and written language by many millennia. Its existence shows that storytelling did not arise as a byproduct of complex societies. Instead, narrative thinking was already present among mobile hunter gatherers.

Visual stories may have helped transmit knowledge, coordinate group behavior, or preserve collective memory. A cave wall served as a stable medium in a changing landscape. The Sulawesi painting demonstrates that structured communication was essential to human groups long before villages or cities formed.

8. Migration routes carried symbolic traditions.

Sulawesi lies along ancient migration corridors connecting mainland Asia to Australia. Early humans passing through the region brought more than tools and survival strategies. They carried symbolic practices that adapted to new environments.

The presence of narrative art here suggests that storytelling traveled with people and evolved locally. Each region added its own subjects and styles. The Sulawesi scene represents one expression of a broader human tendency to record shared experiences visually during migration.

9. Many caves remain unexplored.

Only a fraction of Sulawesi’s caves have been surveyed or dated. Dense vegetation and steep karst terrain limit access to many sites. Each unexplored cave has the potential to contain older or equally significant artwork.

As dating techniques improve, researchers expect the timeline of narrative art to extend further back. The current discovery may represent an early example, not the beginning. Continued exploration is likely to reshape understanding of when and where visual storytelling first emerged.

10. The discovery fixes storytelling to deep time.

The Sulawesi painting anchors narrative thinking to a specific place and minimum age. It is no longer hypothetical or inferred from later evidence. The scene provides a concrete data point showing that humans were constructing visual stories more than fifty thousand years ago.

This finding establishes narrative art as an early and measurable behavior. It reframes storytelling as a foundational human trait rather than a late cultural development. The cave wall does not summarize history. It documents a moment when humans were already capable of representing events, relationships, and meaning through images.