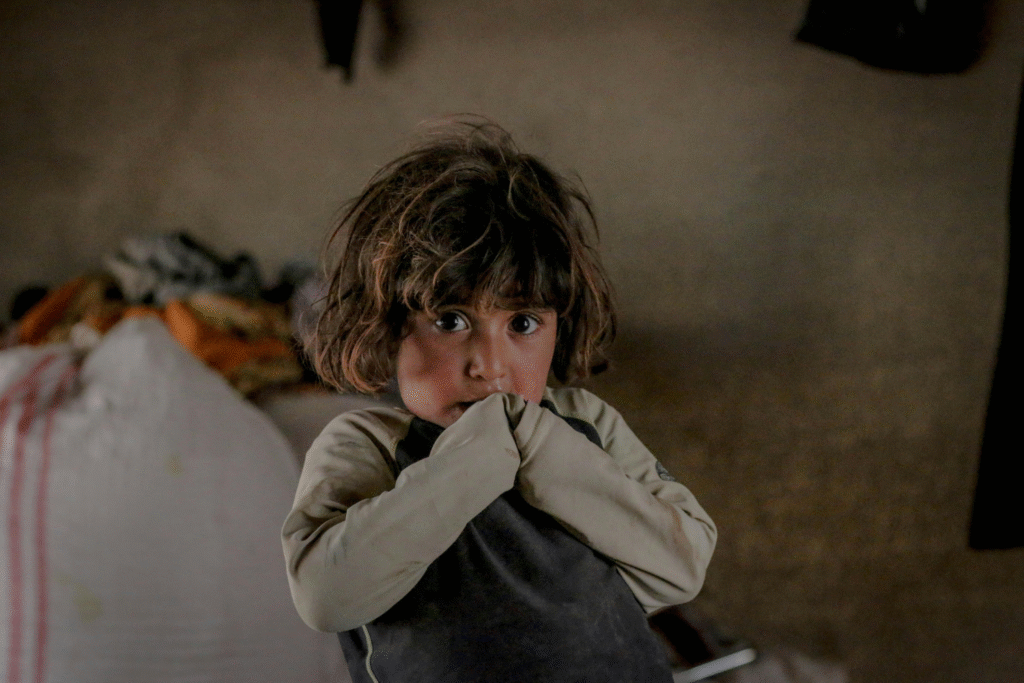

A crisis deepens as farms fail and children suffer.

Central America is watching an unsettling trend unfold. Harvests are faltering, children are eating less, and families are running out of options. The region known as the Dry Corridor, stretching through Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua, is now a hotspot of human vulnerability. Droughts linger longer, storms arrive stronger, and rural communities depending on rainfed crops are caught in the middle. But climate stress isn’t acting alone. Historical inequality, fragile markets, and thin safety nets are all feeding into this cycle that leaves the youngest with the least protection.

1. The Dry Corridor defines a region under siege.

The Dry Corridor is not a metaphor but an actual geographic strip where weather swings are extreme and small farmers live on the edge of survival. Rain comes late, disappears early, and soil dries out before crops can root. According to the World Food Programme, about 10.5 million people live in this zone, most relying on rainfed agriculture. Families here don’t just face weather, they face a narrowing margin of survival where children skip meals because the land no longer feeds them, and the crisis is accelerating faster than expected.

2. Droughts keep shrinking corn and bean harvests.

Year after year, farmers describe the same nightmare: seeds planted in dust, fields withering under skies that stay clear for months. Corn and beans, the staples of the diet, vanish before they can mature. Malnutrition follows quickly, hitting children hardest as diets collapse into monotony or outright scarcity. Families sell livestock, borrow money, or reduce food intake just to scrape by. This isn’t just anecdotal—it’s been documented in climate and agriculture studies across Guatemala and Honduras, reported by Trócaire. The outcome is predictable: more children fall into hunger, their bodies absorbing the punishment of failed rains.

3. Child malnutrition rates are climbing with alarming speed.

Clinics scattered across the Dry Corridor are noting a steady rise in stunting and wasting among children under five. Parents arrive with infants who are lethargic, undersized, and fragile, while doctors know recovery will be long. The UNICEF and ECLAC joint assessment makes clear that climate disruption is not just a background issue but a central driver of this surge. Stunted growth today means limited potential tomorrow, leaving children locked in a cycle of disadvantage. Every failed harvest compounds the risk, and the numbers are showing it more starkly each season.

4. Land inequality leaves families trapped in poverty.

Owning a small plot is often the only buffer, yet even those who farm their own land are squeezed by unequal access to credit and support. Many don’t have secure titles, limiting investment or protection. Wealthier landholders adapt with irrigation or new seeds, while poorer households watch their soil fail. When land is scarce or insecure, children grow up with fewer resources, fewer meals, and little chance of breaking the cycle. Climate shocks hit hardest where inequality has already tilted the playing field steeply.

5. Weak rural infrastructure magnifies the losses.

In regions where roads are barely passable and irrigation systems don’t exist, every climate swing becomes a disaster multiplier. If a flood wipes out crops, farmers can’t transport what survives to markets. When a drought hits, there’s no backup water supply. Families lose food, income, and stability all at once, with children often the first to pay the price. Better infrastructure could soften the blow, but for now, the absence of it makes every harvest more precarious than the last.

6. Local markets are failing under climate and cost.

Village markets used to buzz with fresh produce and exchanges that kept families afloat. Now stalls stand half empty, prices spike, and many families cannot afford what’s left. Children experience this directly when plates hold fewer vegetables, less protein, and smaller portions. Inflation fueled by scarcity makes poverty heavier. Parents once able to stretch earnings into balanced meals are instead stretching thin soups, and kids carry the hunger into schoolrooms and workplaces, shaping their future options in real time.

7. Migration is reshaping entire communities and families.

With each failed harvest, more families weigh the choice to leave. Parents take children on dangerous journeys north, or split families by leaving them behind with grandparents. Schools lose students, villages lose workers, and children lose stability. Migration is not just a political story—it is a food story, a survival story. For kids, it means disrupted education, hunger, and a childhood marked more by uncertainty than by security.

8. Education systems strain as hunger disrupts learning.

Teachers notice before policymakers do. Students arrive too tired to focus, fall asleep at desks, or skip school altogether because food is scarce at home. Hunger is a quiet thief, stealing attention and long-term opportunities. Education once promised a way out of poverty, but climate-driven hunger is pulling that ladder away. Entire classrooms shrink as more children are forced to abandon studies, leaving an entire generation less prepared to adapt or compete in a changing world.

9. Government and aid resources cannot match the pace.

Emergency food programs exist, but rural communities often wait weeks for supplies, if they arrive at all. Governments balance debts and budgets while climate disasters multiply, leaving aid stretched thin. International support fills gaps, yet it rarely keeps up with the need. For children, this means months of inadequate nutrition while bureaucracies move slowly. The gap between urgency and response creates a vacuum that hunger fills all too easily.

10. The future of children hangs in fragile balance.

Every skipped meal, every missed class, every forced migration makes the future narrower for children in the Dry Corridor. Climate change may be the spark, but inequality, poor infrastructure, and weak safety nets keep the fire burning. Unless there is stronger adaptation, better protection, and sustained support, this crisis will define an entire generation. For now, the children of Central America bear the weight of a changing climate and the heavy inheritance of systems not built to protect them.