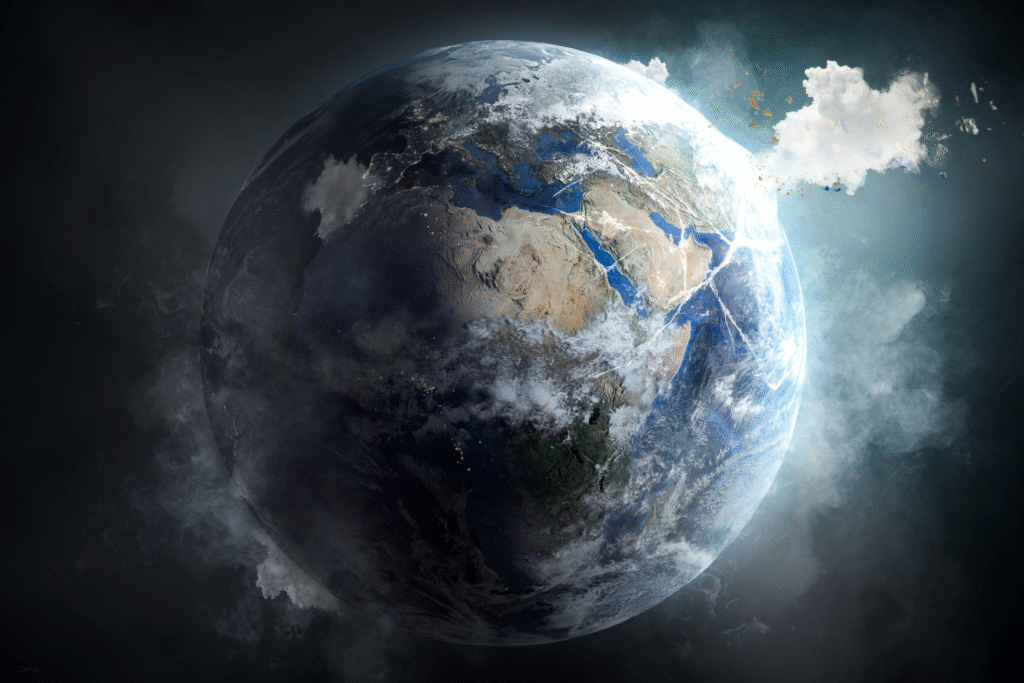

The planet is rearranging life faster than expected.

The natural world is no longer shifting in slow, almost invisible ways. Temperature lines are sliding across maps, seasons are losing their familiar rhythm, and species are responding in real time. Changes that once unfolded over centuries are now visible within a few decades, sometimes within a single generation. These shifts are not theoretical projections. They are being observed in forests, oceans, grasslands, and wetlands right now. The most unsettling part is not that ecosystems are changing, but how quickly their internal balance is being rewritten.

1. Spring now arrives early and leaves chaos behind.

Here’s a more specific, grounded rewrite with concrete places, species, and timelines, while keeping the science tight and readable:

Across temperate regions of North America and Europe, spring now begins measurably earlier. In Massachusetts, lilacs and honeysuckle are flowering up to three weeks sooner than they did in the mid twentieth century. Soils warm earlier, triggering plant growth before many insects have completed winter development. When native bees emerge late, flowers like trout lily and spring beauty often bloom without effective pollination, reducing seed production across entire forest understories.

This timing breakdown ripples upward. In the northeastern United States, migratory birds such as the black throated blue warbler arrive on traditional daylight cues, only to miss peak caterpillar abundance by days or weeks. Long term monitoring has documented these mismatches at sites from New England to Scandinavia, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Missed meals reduce chick survival, gradually thinning populations even without habitat loss.

2. Animals are climbing mountains and fleeing poleward.

As average temperatures climb, species are physically shifting their ranges to survive. In the western United States, pikas have retreated upslope by hundreds of feet in the Sierra Nevada as lower elevations exceed their heat tolerance. Moose populations in Minnesota are declining while their range contracts northward into Ontario. Butterflies such as the Edith’s checkerspot have disappeared from Mexico and southern California, persisting only at higher elevations where spring temperatures remain cooler.

These movements create hard limits. Alpine species in the Rockies and Alps face extinction once mountaintops are reached. In the North Atlantic, cod and mackerel now track colder waters toward Iceland and Greenland, disrupting fisheries in New England and northern Europe. These coordinated shifts closely match global warming patterns, as reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, confirming temperature as the primary driver.

3. Coral reefs are bleaching faster than recovery allows.

Coral reefs survive within an extremely narrow temperature range. When water temperatures rise just one to two degrees Celsius above normal for several weeks, corals expel the symbiotic algae that supply most of their energy. This process, known as bleaching, once occurred infrequently enough for recovery. Now, marine heat waves strike every few years, leaving reefs no time to rebuild tissue or restore lost algae before the next stress event arrives.

The consequences are visible across northeastern Australia. Between 2016 and 2022, large sections of the Great Barrier Reef experienced repeated mass bleaching, with shallow reefs losing more than half their coral cover. Long term monitoring has documented widespread structural collapse, as discovered by the Australian Institute of Marine Science. As reefs flatten, fish populations decline, shoreline erosion increases, and coastal communities lose critical natural storm buffers.

4. Invasive species are gaining ground with warmer winters.

Cold winters once acted as natural barriers, killing off non native species before they could establish permanent footholds. As minimum temperatures rise, those barriers weaken or vanish entirely. In the northeastern United States, emerald ash borers now survive winters that once limited their spread. Invasive ticks carrying Lyme disease persist year round across New England and the Upper Midwest, expanding their range northward into Canada as cold thresholds disappear.

With winter die offs reduced, invasive species gain time and numbers. Forest pests overwhelm regeneration cycles, killing mature trees faster than seedlings can replace them. Invasive plants such as kudzu and Japanese knotweed alter soil chemistry and light availability, suppressing native growth. Species that evolved with seasonal resets face constant pressure instead, accelerating ecosystem imbalance rather than allowing gradual adaptation.

5. Predator and prey relationships are falling out of sync.

Predators and prey depend on precise seasonal timing that evolved over thousands of years. As climate shifts disrupt that timing unevenly, those relationships begin to unravel. In the Arctic, caribou now calve earlier in response to warmer springs, while the plants they depend on reach peak nutrition even earlier. Calves arrive after the highest protein window has passed, weakening survival rates before predators even enter the equation.

Predators face parallel disruptions. Arctic foxes and wolves track prey migrations that no longer follow reliable patterns. Some years prey numbers surge briefly, then collapse once predation catches up. In other years predators arrive too late and face food shortages. These destabilized cycles have been documented across tundra ecosystems, where timing errors rather than habitat loss now drive population volatility.

6. Forests are transforming from the inside outward.

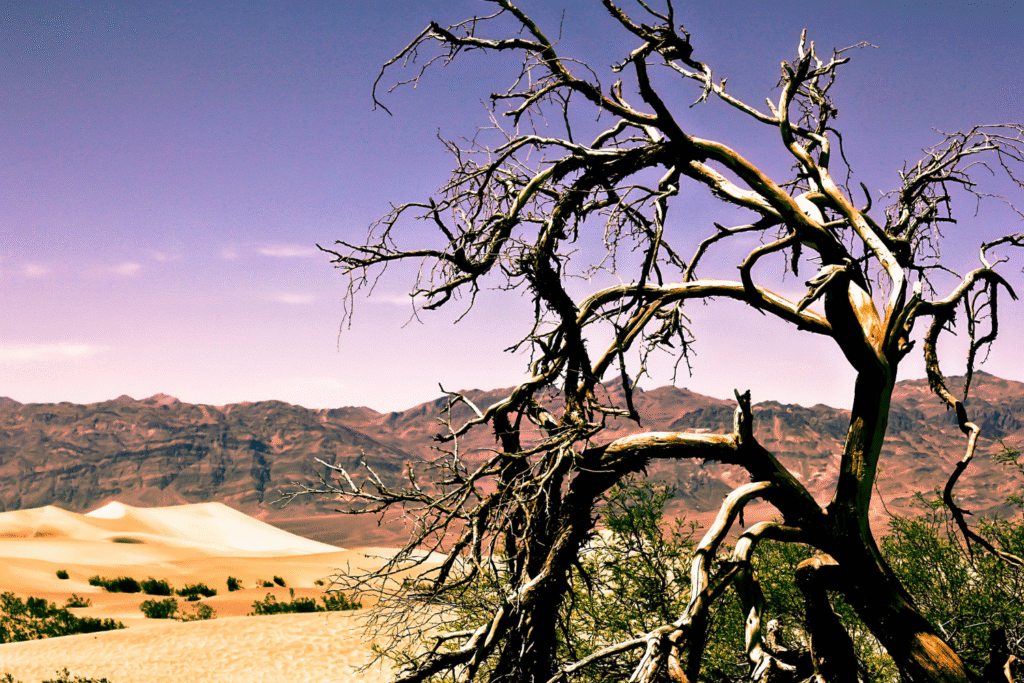

Climate stress reshapes forests years before trees begin to die. In the western United States, prolonged drought has weakened ponderosa pine and Douglas fir stands, reducing resin production that normally protects against insects. As defenses falter, bark beetles spread rapidly, killing trees already stressed by heat and water loss. Similar patterns are unfolding across southern Europe, where beech forests show early decline during repeated summer heat waves.

As sensitive species retreat, drought tolerant trees such as juniper and oak expand into newly available space. These shifts change canopy density, soil moisture retention, and wildfire behavior. Animals that rely on mature conifers lose nesting and foraging habitat. Over time, forests reorganize into ecosystems with different species, fire regimes, and ecological functions rather than simply becoming thinner versions of the past.

7. Wetlands are drying or drowning with little middle ground.

Wetlands depend on stable seasonal water rhythms to function. As climate patterns shift, those rhythms break down. In California’s Central Valley, multi year droughts have dried seasonal wetlands beyond recovery, while sudden atmospheric river storms now flood others for weeks at a time. Plants adapted to gradual rises and falls in water levels fail under both extremes, leaving exposed mudflats or permanently submerged zones.

Along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, saltwater intrusion is pushing inland as sea levels rise, killing freshwater marsh grasses from the roots upward. Inland prairie pothole wetlands across the Dakotas disappear during prolonged dry spells, erasing breeding sites for waterfowl and amphibians. As wetlands vanish, communities lose natural water filtration, storm buffering, and flood protection once provided free by functioning ecosystems.

8. Ocean food chains are reorganizing from plankton up.

Plankton respond rapidly to even small changes in ocean temperature. In the North Atlantic, warming waters have shifted communities from larger, energy rich copepods to smaller plankton species with lower caloric value. Fish such as Atlantic cod and haddock must consume far more prey to meet basic energy needs, often failing to keep pace during critical growth periods.

This nutritional deficit moves up the food web. Juvenile fish grow more slowly and reach reproductive age later, reducing population resilience even where fishing pressure is low. Seabirds like puffins and marine mammals such as humpback whales track prey into unfamiliar waters or abandon historical feeding grounds. Marine ecosystems reorganize gradually through energy loss rather than sudden collapse.

9. Disease is spreading into previously safe habitats.

Pathogens track climate limits as closely as the species they infect. As temperatures rise, fungi, parasites, and viruses persist in regions that once suppressed them. In Central America and the western United States, the chytrid fungus has spread into cooler high elevation habitats, devastating amphibian species that evolved without resistance. Warmer nights allow the pathogen to remain active year round instead of retreating seasonally.

In temperate forests, insects now carry diseases farther north. Ticks spread Lyme disease into southern Canada, while mosquitoes transmit West Nile virus into regions previously unaffected. Tree pathogens such as sudden oak death expand during warmer wetter winters. These diseases can remove key species within a few seasons, reshaping ecosystems before predators, competitors, or plants can adjust to the sudden loss.

10. Extinction risk rises as adaptation windows close.

Adaptation depends on time, genetic variation, and room to move. Rapid climate change strips away all three. Long lived species such as old growth trees and large mammals cannot reproduce fast enough to track shifting conditions. Specialists that rely on narrow temperature ranges or specific food sources lack flexibility. At the same time, roads, farms, and cities fragment landscapes, blocking migration paths that once allowed gradual range shifts.

The outcome is a rise in local extinctions that rarely make headlines. Species disappear from individual watersheds, valleys, or reefs long before they vanish globally. Ecosystems become simpler as key players drop out. With each quiet loss, resilience weakens, leaving systems less able to withstand drought, heat, disease, or future climate shocks.