What declassified records now quietly confirm.

The Cold War was fueled by fear, speed, and the belief that falling behind could mean national collapse. Scientific research became an extension of military strategy, often conducted behind sealed doors and vague project names. In that environment, dogs were quietly pulled into experiments meant to answer urgent questions about survival, endurance, and exposure. Decades later, fragments of declassified material reveal how widespread these programs were, how intentionally they were hidden, and how deeply they shaped modern military science.

1. Military labs quietly treated dogs as test instruments.

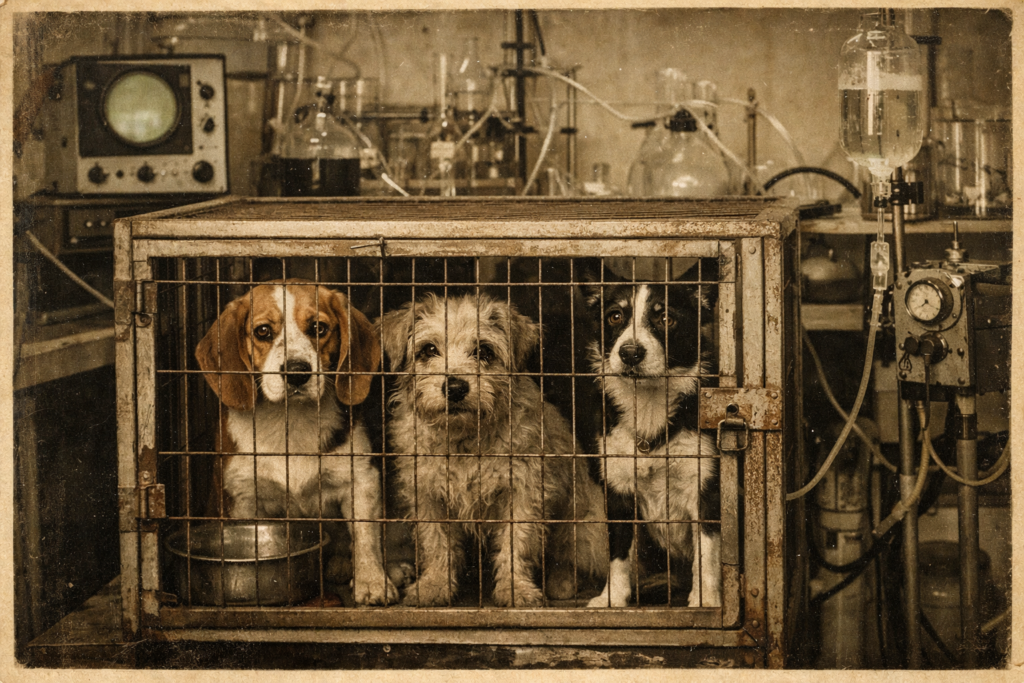

During the early Cold War, military research culture framed animals as functional assets rather than sentient beings. Dogs were assigned identification numbers, categorized by weight or tolerance, and transferred between facilities under project codes that concealed their purpose. Research notes emphasized data reliability, exposure thresholds, and repeat testing while avoiding language that acknowledged pain or mortality. This approach allowed experiments to proceed quickly, insulated from ethical debate or public scrutiny.

At facilities in Maryland, New Mexico, and Ohio, dogs were used in blast, radiation, and endurance experiments, according to the U.S. National Archives. Many files end abruptly, suggesting outcomes that were never intended to be revisited or questioned.

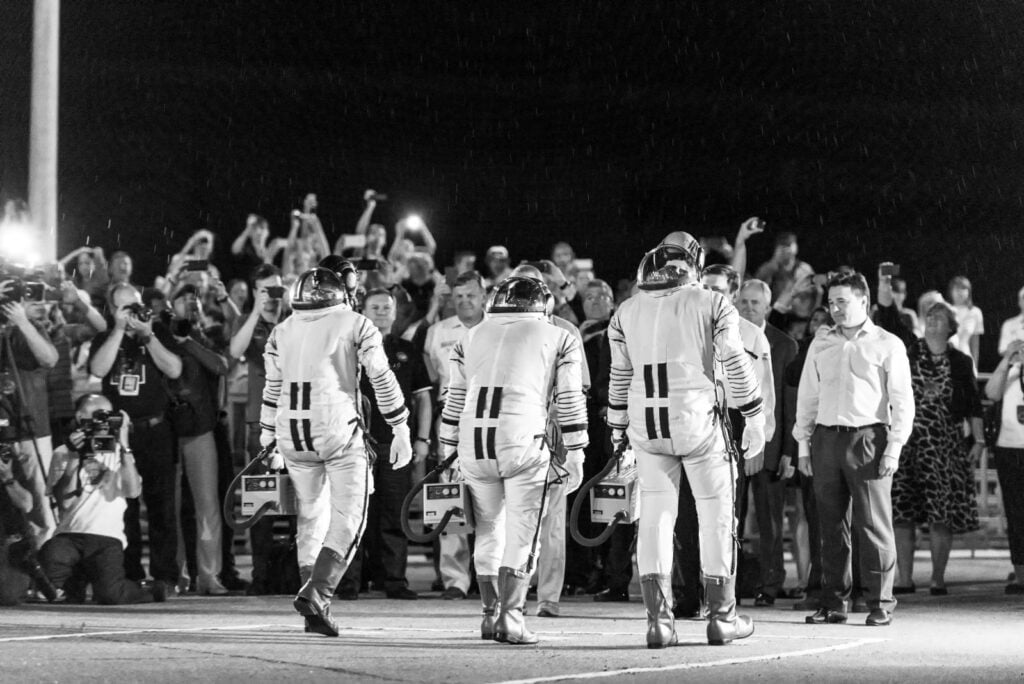

2. Aerospace research pushed dogs beyond biological limits.

As aviation and space technology advanced faster than human safety standards, dogs were used to approximate how bodies respond to extreme forces. Researchers subjected them to high acceleration, pressure changes, and oxygen deprivation to measure loss of consciousness, cardiac stress, and neurological response. These trials were designed to replicate early spaceflight conditions that no human could yet endure safely.

At Wright Patterson Air Force Base, dogs underwent centrifuge testing and low oxygen experiments, as reported by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. The data helped shape cockpit design, pressure systems, and emergency protocols later used by pilots and astronauts.

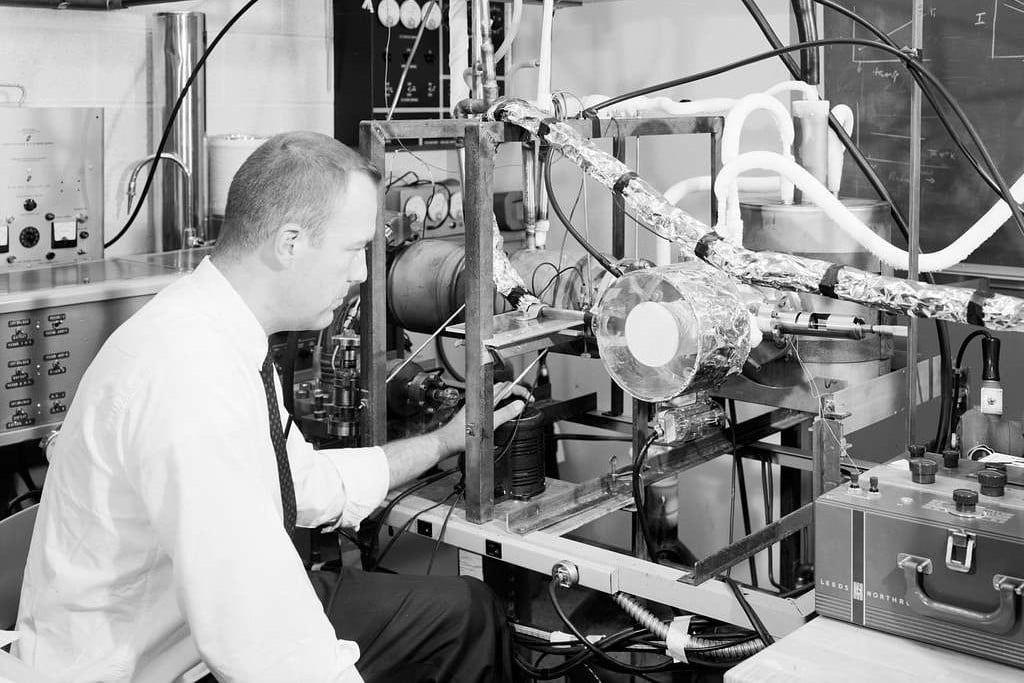

3. Chemical warfare programs relied heavily on canine subjects.

Chemical weapons development required living organisms to track how toxins affected the nervous system, lungs, and circulation in real time. Dogs were chosen for their predictable physiological reactions, allowing researchers to observe symptom onset, progression, and the effectiveness of experimental antidotes. Trials focused on nerve agents, choking compounds, and exposure timing under tightly controlled conditions.

At Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, dogs were exposed to chemical agents and countermeasures during classified testing, as stated by the U.S. Army Public Health Center. Long term neurological and respiratory damage was often noted internally but rarely disclosed publicly.

4. Soviet space programs also depended on canine testing.

On the other side of the Iron Curtain, dogs became central to early Soviet space ambitions. Long before human cosmonauts flew, dogs were used to validate life support systems, reentry survival, and capsule stability. Training involved isolation chambers, vibration platforms, and confinement lasting days or weeks, designed to mimic orbital conditions.

Facilities near Moscow conducted repeated launch simulations using dogs to test spacecraft reliability. Many missions were never publicly acknowledged, and survival was secondary to whether usable data was transmitted back to ground control.

5. Behavioral conditioning studies aimed to control stress responses.

Cold War strategists feared psychological breakdown as much as physical injury. Dogs were used to study how fear, confusion, and sensory overload altered behavior under sustained pressure. Researchers tracked obedience, memory disruption, and recovery time when animals were exposed to unpredictable and stressful environments.

Laboratory trials employed loud noise, flashing light, confinement, and isolation to induce stress reactions. Findings from these studies influenced later military training programs focused on resilience, captivity survival, and resistance to interrogation techniques.

6. Radiation exposure experiments mirrored nuclear anxieties.

As nuclear weapons reshaped global strategy, military planners sought biological answers to radiation exposure limits. Dogs were placed at varying distances from controlled radiation sources to observe organ damage, immune suppression, and delayed illness. Researchers monitored changes over weeks and months, attempting to define survivability thresholds.

Many studies followed atmospheric nuclear tests in Nevada, pairing environmental fallout measurements with biological outcomes observed in laboratory animals. Results were classified for decades, as they revealed vulnerabilities governments preferred not to acknowledge.

7. Medical countermeasures were tested before battlefield use.

Rapid medical advancement was seen as essential to maintaining combat readiness. Dogs were used to test trauma treatments, surgical techniques, and emergency medications before human deployment. Experiments focused on blood loss control, shock response, and survival during delayed evacuation scenarios.

Military hospitals practiced amputations, transfusions, and emergency procedures on canine subjects. These techniques later saved human lives in conflicts such as Korea and Vietnam, though the animals involved were rarely acknowledged in official medical histories.

8. Records were deliberately fragmented across agencies.

Cold War secrecy ensured that no single archive told the full story. Records were divided among military branches, renamed under unrelated project titles, or destroyed outright. This fragmentation made oversight nearly impossible and shielded programs from accountability.

Historians now reconstruct these efforts using veterinary logs, funding trails, and transport records listing dogs by the thousands. Even with careful cross referencing, large gaps remain, suggesting intentional erasure rather than simple loss.

9. Public awareness lagged decades behind the research.

Most programs remained unknown until Freedom of Information requests forced partial disclosure. Even then, heavy redactions obscured methods, scale, and outcomes. Early document releases hinted at scope but avoided emotional or ethical context.

In the 1990s, broader disclosures revealed how deeply animals were embedded in Cold War research. By then, public debate arrived too late to affect accountability or restitution.

10. Ethical standards shifted only after irreversible damage.

Modern military research now operates under strict animal welfare oversight shaped directly by Cold War excesses. Review boards require justification, harm reduction, and alternatives whenever possible. These safeguards reflect lessons learned through irreversible loss.

They exist because thousands of dogs bore the unseen cost of fear driven science. That legacy continues to shape how military research balances urgency against ethics today.