Gaps in detection systems leave humanity relying on luck more than readiness.

The last few months have offered a stark reminder of how fragile Earth’s defenses really are. NASA confirmed that a newly discovered asteroid, roughly the size of a football field, passed within 40,000 miles of Earth in early August—closer than many satellites. The unsettling part wasn’t its size but the fact that astronomers spotted it only two days before it zipped past.

That asteroid, cataloged as 2024 OK1, isn’t unique. Dozens of city-killer–scale rocks are detected only after they’ve already buzzed the planet. The weak spots in global monitoring systems—limited telescope coverage, poor southern hemisphere visibility, and patchy funding—mean Earth’s safety often comes down to chance. The data make clear that for now, the planet is playing catch-up with the solar system.

1. Near misses keep happening with little warning.

The asteroid 2024 OK1, discovered just 48 hours before it passed, stretched an estimated 500 feet across. That makes it large enough to flatten a metropolitan area if it had hit. Scientists admitted they had little chance to prepare, since the rock was only spotted on approach, as reported by NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies.

These late detections reveal how vulnerable the system is. Without advance notice, governments would have no time to evacuate populations or mount a deflection mission. The asteroid moved on, but the margin of safety was alarmingly slim.

2. Telescopes miss more than they catch.

Despite years of investment, astronomers still estimate that only about 40 percent of potentially hazardous asteroids larger than 140 meters have been cataloged. That leaves thousands of untracked rocks capable of causing regional devastation, ending the sentence with the European Space Agency.

The main gaps come from limited telescope coverage. Clouds, daylight, and blind spots near the Sun obscure many objects. Asteroids approaching from the southern hemisphere often go unnoticed until they’re nearly past. This patchwork system makes detection as much a matter of timing and luck as of technology.

3. Small differences in size can mean massive consequences.

A 150-foot asteroid might explode in the atmosphere, creating a blast like the 2013 Chelyabinsk event in Russia, which injured 1,600 people. Double that size, and the energy increases tenfold, enough to obliterate a city center. Scientists stress that distinguishing these sizes is critical, yet current detection networks often can’t provide reliable estimates until after discovery, as stated by the Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

The difference between a close call and a catastrophe can be a matter of hours. Yet the system isn’t built to give reliable early warnings at these scales. For communities on the ground, that means no sirens, no alerts, only the hope that impact doesn’t happen.

4. Funding lags behind the scientific warnings.

NASA has a mandate to detect 90 percent of dangerous asteroids over 140 meters, but progress is slow. The planned NEO Surveyor space telescope was delayed years due to budget cuts, leaving ground-based systems to shoulder the load. Scientists argue that without more investment, detection rates will remain stuck at partial coverage.

This gap isn’t about lack of know-how but political will. Space telescopes cost billions, but so does rebuilding a city—or worse, losing one. The cost of prevention looks small compared to the risks of inaction.

5. Southern skies remain poorly guarded.

Most tracking facilities sit in the northern hemisphere, leaving vast stretches of southern skies under-monitored. That’s why several recent near-Earth objects were first picked up by smaller observatories in Brazil and South Africa, long after they had already approached Earth.

This geographic imbalance makes southern continents more vulnerable. If an impactor approached from below Earth’s equator, it could remain invisible until hours before arrival. The system’s uneven reach makes global safety dependent on where an asteroid happens to come from.

6. Warning times can shrink to hours, not days.

The public imagines years of notice for an incoming asteroid, but reality often looks very different. When smaller near-Earth objects are discovered, the time between detection and closest approach is frequently less than a week. In some cases, it’s less than 24 hours.

That leaves no practical window for preparation. Evacuations, impact predictions, or even accurate size estimates are often impossible under those conditions. The margin for meaningful response shrinks to zero.

7. Chelyabinsk was the wake-up call the world ignored.

The 2013 explosion over Russia, caused by a 65-foot asteroid, generated energy 30 times greater than Hiroshima. No one saw it coming. Despite the global shock, follow-through on planetary defense investment stalled after initial interest.

Instead, the event has become a case study in complacency. People witnessed shattered windows and widespread injuries, but policy shifted little. The reminder was clear—impacts happen—but the political urgency faded once the headlines disappeared.

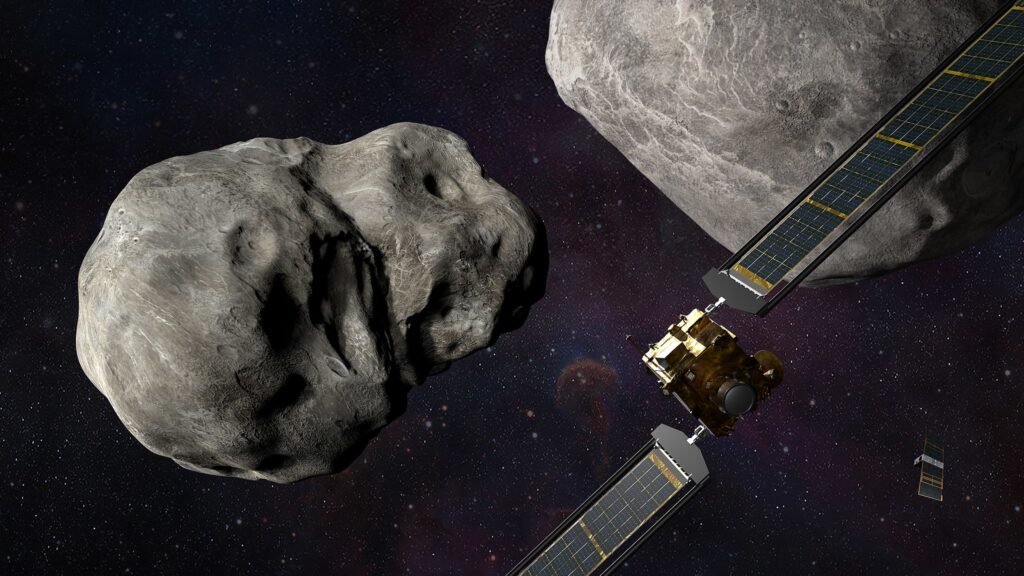

8. Deflection technology is still in its infancy.

NASA’s DART mission in 2022 proved it’s possible to alter an asteroid’s path by striking it with a spacecraft. The success marked the first real-world demonstration of planetary defense. Yet scientists caution that scaling this technology for larger or late-detected asteroids is another challenge entirely.

Deflection works only with years of advance notice. For rocks spotted days away, the window for such intervention has already closed. That mismatch between capability and detection timelines highlights the fragility of current defenses.

9. Coordination across countries remains fragmented.

While agencies like NASA and ESA share data, there is no binding international framework for coordinated response. Who decides whether to evacuate, launch deflection missions, or fund emergency systems remains murky.

Asteroids don’t respect borders, but the systems designed to track them still operate nationally. That gap could prove disastrous if a dangerous asteroid is spotted with only days to spare. Coordination, scientists argue, must catch up before luck runs out.

10. The next close pass is already on the calendar.

Astronomers are tracking 99942 Apophis, a 1,200-foot asteroid expected to pass closer than geostationary satellites in 2029. Unlike 2024 OK1, this one is well-studied and considered non-threatening for now. Still, its proximity will provide an unnerving spectacle and a reminder of what’s at stake.

That looming encounter underscores the two realities of asteroid defense: some threats are known years in advance, while others slip by with barely a day’s warning. Between those extremes lies the fragile balance of preparedness that defines Earth’s current planetary defense.