Science can copy a body, but not a bond.

Pet cloning sounds like a scientific loophole for grief, but the truth is far more complex. The idea of bringing your dog “back” through genetics captures hearts and headlines alike, yet the result isn’t a perfect copy. It’s a scientific echo, a mirror image made from living cells but stripped of experience. Behind the sleek labs and glossy promises lies a process that’s still unpredictable, emotionally charged, and ethically tangled. What cloning really revives isn’t the past—it’s our struggle to hold on to it.

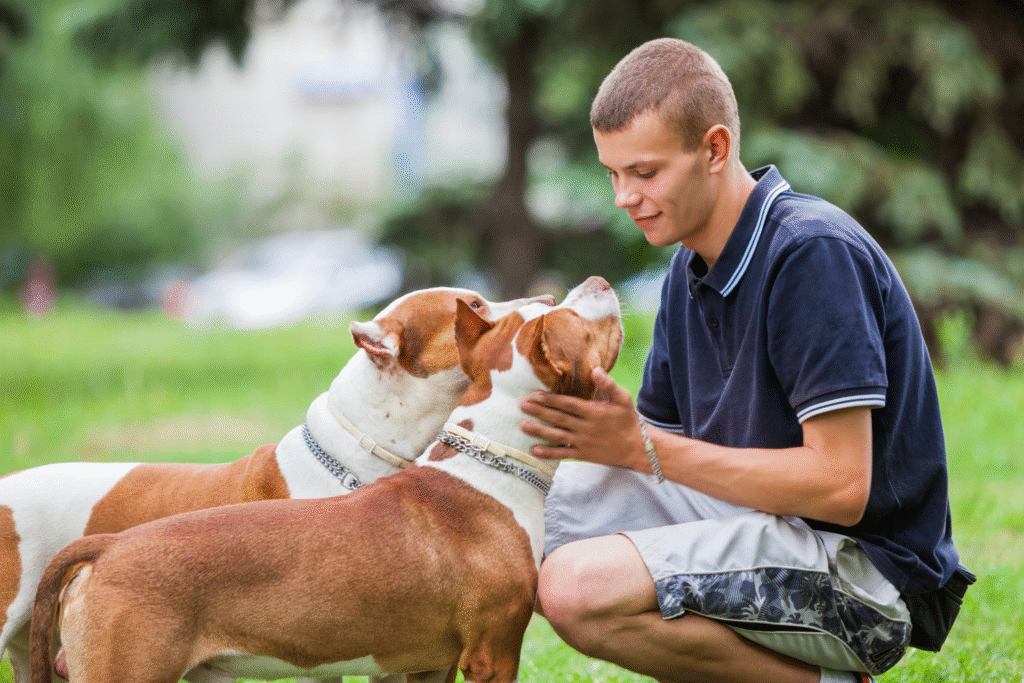

1. A cloned dog shares identical DNA, not the same mind.

Cloning recreates a dog’s genetic code, but not the life that shaped its personality. As stated by the American Veterinary Medical Association, a clone is genetically identical, yet each animal’s environment, early experiences, and human interactions influence who they become. So, while a cloned dog may have the same markings and bone structure as your original pet, it won’t necessarily tilt its head the same way or chase the same toy. DNA is a foundation, not a full story.

This difference becomes clear once the clone starts growing and developing its own behaviors. Owners expecting an instant continuation of their lost pet often face emotional whiplash when they realize this “new” dog feels like a stranger. The resemblance can be hauntingly close, but it lacks the memory—the shared history—that made the original bond irreplaceable.

2. The cloning process starts with a single preserved cell.

Scientists begin by taking a tiny biopsy, often from the dog’s skin, and preserving those cells in a frozen state. When it’s time, a donor egg from another dog is stripped of its nucleus and fused with one of those preserved cells to create a cloned embryo. That embryo is then placed inside a surrogate dog to carry it to term. As reported by the National Human Genome Research Institute, only a fraction of these embryos develop successfully, and even fewer survive birth.

This intricate sequence sounds almost cinematic, but it’s delicate and unpredictable. Each stage can fail for reasons scientists still don’t fully understand. The process blurs the line between reproduction and resurrection, and while it’s rooted in hard biology, it forces people to confront deeply emotional questions about what “bringing a pet back” really means.

3. Companies like ViaGen are already cloning family pets.

Pet cloning isn’t a concept for the future, it’s happening right now. As discovered by The New York Times, ViaGen Pets in Texas has been cloning dogs and cats for paying clients, including celebrities, for nearly a decade. The company charges up to $50,000 for a cloned dog, with the process taking several months from preserved cell to living puppy. They present it as “continuing a legacy,” a phrase designed to comfort grieving owners.

Still, behind that comforting pitch lies a controversial business model. The idea of paying to re-create a living being divides veterinarians and ethicists. Some see it as a technical marvel, while others see it as commodifying life. Every cloned puppy born represents not just a biological success but a modern moral dilemma about what humans are willing to spend, or sacrifice, for love.

4. The success rate for cloned embryos is surprisingly low.

For every healthy clone that survives, many embryos fail along the way. Scientists estimate that fewer than one in five cloned embryos results in a live puppy. Each success hides a string of failures, unsuccessful pregnancies, miscarriages, and developmental defects. The process remains inefficient even with decades of refinement, and that inefficiency often gets glossed over in marketing materials meant to comfort buyers.

Researchers continue to improve techniques to minimize the loss of embryos and reduce the strain on surrogates. But the reality is harsh: for one perfect clone, multiple dogs endure invasive procedures. The science may be remarkable, but the human desire to overcome death still comes at a biological cost.

5. Even identical twins aren’t truly identical in personality.

Think of human identical twins: same genes, different people. That same principle applies to clones. Two animals with identical DNA can behave in dramatically different ways depending on how they’re raised, what they experience, and the environment they grow up in. Even the tone of voice you use or the layout of your home can subtly reshape their behavior over time.

Owners expecting an exact repeat of their late dog often end up realizing they’ve brought home a brand-new individual. The clone might respond differently to certain toys or be more cautious than the original. Personality, it turns out, is an unpredictable blend of nature and nurture—and cloning only guarantees one of those ingredients.

6. Cloning doesn’t transfer memories or learned behaviors.

DNA holds genetic information, not memories. The neurons that stored your dog’s memories, the smell of your house, the sound of your voice, died with its brain. No technology can reassemble those emotional connections. So while a cloned dog may wag its tail in a similar way, it won’t know your scent, your routine, or the life you shared before.

This is where many owners hit the hardest realization. What cloning gives you is a fresh life with familiar genetics, not a reunion. Some find peace in that, treating their clone as a symbolic continuation, while others struggle with the eerie sense that something essential is missing—because it is.

7. The procedure raises serious animal welfare concerns.

Each successful clone is supported by a hidden network of animals used for egg donation, embryo carrying, and surrogacy. These dogs often endure multiple surgeries and pregnancies, many ending in complications. Critics argue that cloning for emotional comfort risks turning animals into biological instruments. Animal welfare organizations warn that the suffering of surrogate dogs outweighs the benefits of cloning’s emotional novelty.

Even with stricter oversight, the ethical shadow remains. Science can replicate the body of a beloved pet, but at what cost to the lives used along the way? For some, that trade-off is too high to justify the emotional closure cloning promises.

8. Genetic age and real age don’t always match.

Clones may start as newborns, but their DNA begins life with the genetic age of the donor. That means cloned animals sometimes face the same inherited weaknesses or accelerated aging patterns as their originals. Scientists studying cell longevity are still trying to understand how cloning affects lifespan, and while many clones live normal lives, the risk of premature aging remains.

This phenomenon isn’t visible right away, it’s biological, unfolding over years. Owners might assume their cloned dog will live longer or be healthier, but the cells inside tell another story: that of an organism already marked by its predecessor’s genetic time clock.

9. Emotional attachment drives the cloning industry forward.

Grief is powerful enough to fuel an entire industry. For many, cloning isn’t about science; it’s about refusal, refusal to let go. Seeing a new dog with the same face feels like a promise fulfilled, even if the heart knows better. Pet cloning companies thrive on this emotional currency, offering comfort in exchange for continuity.

And yet, many owners describe the experience as bittersweet. The cloned pet can’t fill the same emotional space, because the relationship, the invisible bond between two beings—can’t be manufactured. Science may hand us resemblance, but only life hands us connection.

10. The next frontier may not be cloning at all.

Instead of repeating the past, future research is steering toward genetic enhancement. Scientists are exploring how to edit animal DNA to prevent diseases, extend lifespans, or improve resilience. Cloning might fade as these new frontiers advance, shifting the focus from duplication to preservation.

That shift reframes what we really want from science. Maybe the goal isn’t to bring our dogs back as they were, but to understand what made them special in the first place, and protect that beauty in the living pets still beside us. The truest form of preservation, after all, may not come from copying life, but from caring for it differently.